I wasn’t focused on stained-glass windows when I walked into the auction house some years ago for a sale of works by African American artist Frank J. Dillon. I wanted a sketchbook that an auctioneer had touted a few days earlier at another sale.

At the auction house, I found several large stained-glass windows – including one with the initial “D” in Old English script – by Dillon. I acknowledged them but largely ignored them. I found the sketchbook in a glass case along with a larger sketchbook whose cover was a stained-glass window in watercolor.

I lost out on those sketchbooks, but I was able to buy some others, as well as a 1906 book titled “Glass Writing” inscribed with Dillon’s name in pencil.

I knew little about Dillon at the time. I learned later that he had spent much of his life working as a commercial stained-glass designer in Philadelphia. In a 1929 Atlanta newspaper article about a traveling exhibition by Black artists, Dillon and others were praised for making art while working day jobs. “Frank J. Dillon is a stained-glass designer,” the article stated.

Among the Dillon items at the auction were miniature drawings of stained-glass windows, similar to those gifted in 1955 to the Free Library of Philadelphia by Oesterle Stained Glass Works in Philadelphia, one of Dillon’s employers.

Were some of these designs created by Dillon?

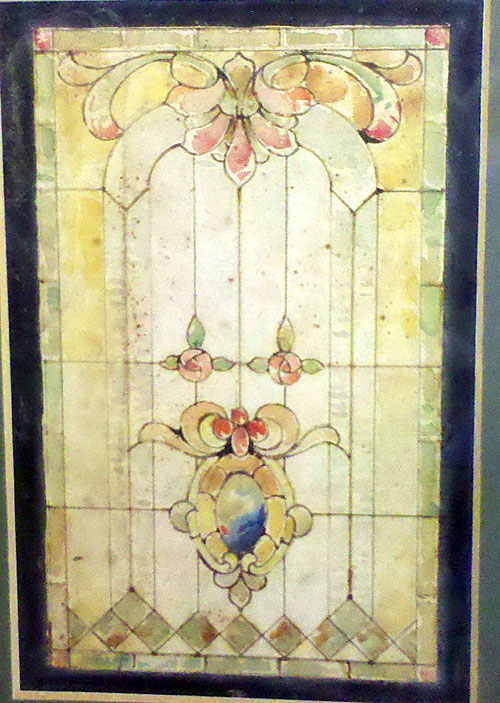

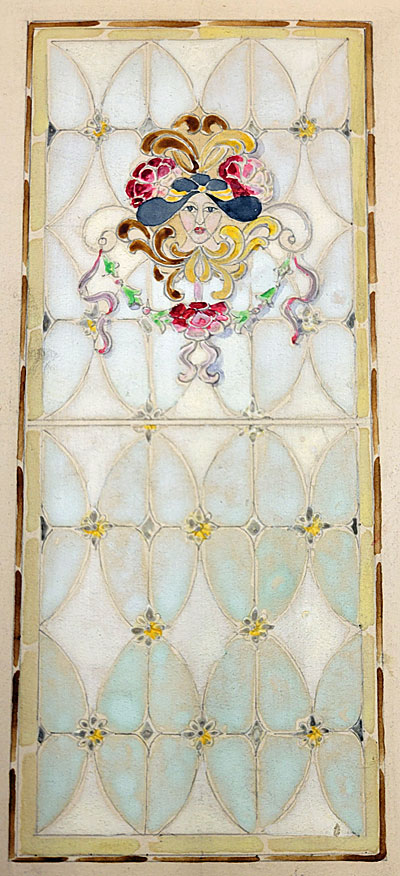

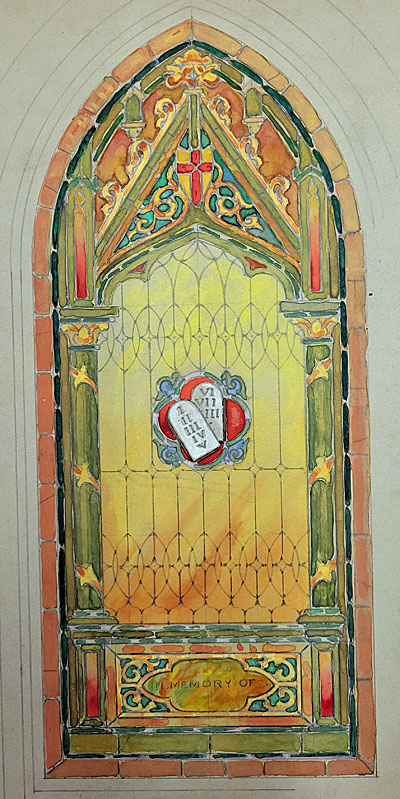

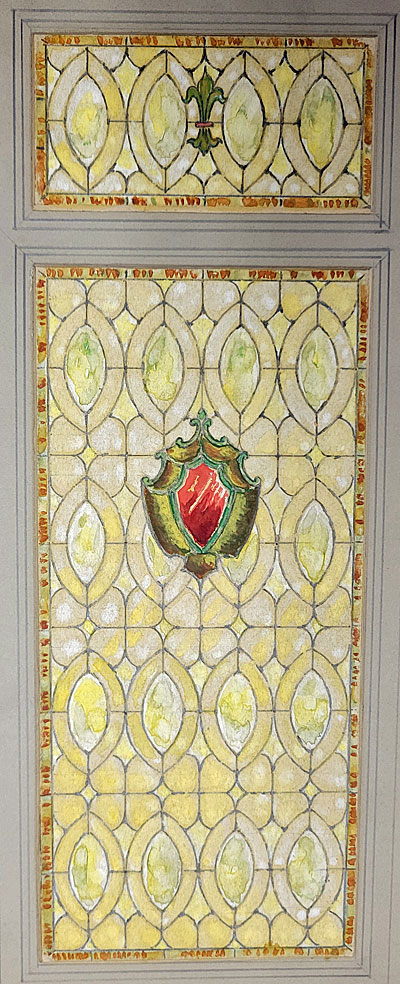

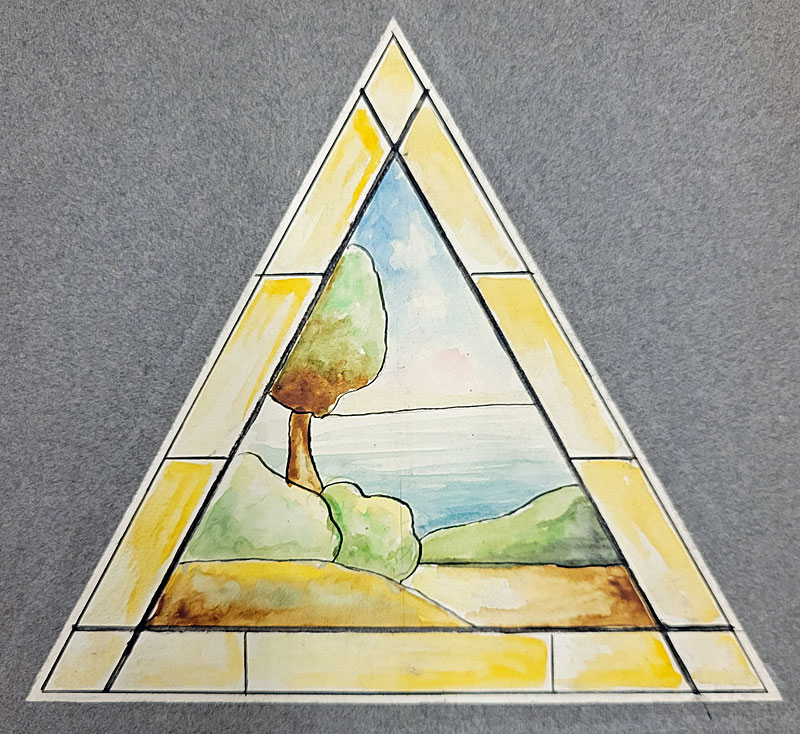

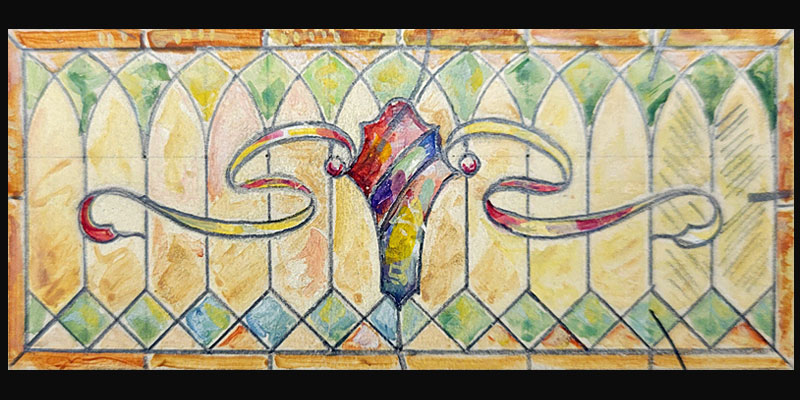

It was a question that both Laura Stroffolino, a curator in the Print and Picture Collection at the library’s Parkway Central branch, and I pondered recently after she laid out more than 25 mini watercolor designs on a table for me. None were signed, so there’s no way to tell who made them. Not much is known about the Oesterle company, except that it was around during the first half of the 20th century, according to the library’s research. (NOTE: Photo at top of page is an enlarged view of one of the library’s samples.)

The company appeared to have designed stained-glass windows primarily for homes. The library samples – no more than 6″ tall and mounted on thin cardboard – were used by Oesterle’s sales staff to display the company’s stained-glass offerings. They were circa 1913 to 1920.

The designs were both soft pastels and bold colors, very detailed and stylish. Two of the boards bore handwritten notes accompanying designs for a bathroom and dining room.

There is no question about at least one major design by Dillon: a stained-glass window located in the chapel at St. Augustine’s University in Raleigh, NC. It was commissioned in 1931 by Anna Julia Cooper – a feminist, activist and teacher – in honor of her late husband the Rev. George A.C. Cooper, ordained a minister by the Episcopal Church in North Carolina in 1876. He died in 1879, a few years after they were married. (Anna Cooper, by the way, is the only woman quoted on the U.S. passport.)

The painting depicts Simon of Cyrene assisting Jesus in carrying the cross – seemingly created in Cooper’s interpretation of the encounter. She wrote a poem about it. At the time, Dillon was said to have been working for Oesterle for 10 years.

The Coopers and Dillon had all attended the then-named Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute at some point. Anna Cooper received degrees from Oberlin College in Ohio before later returning to St. Augustine’s as a teacher while Dillon was a student there.

A 1940 newspaper article about a Dillon exhibit at the Madison (NJ) Library told of their association. He was a:

“well-known Negro painter of Mt. Holly” who was “said to be the only colored person so advanced in the art of stained glass designing as to make it a full-time profession. While a student of Dr. Anna J. Cooper at St. Augustine Academy in Raleigh, North Carolina, he was encouraged to pioneer in this field. Several of his windows may be seen at Frelinghuysen University in Washington, D.C. (where Cooper was then president; the school no longer exists).”

Dillon was born in Mount Holly, NJ, in 1866. He attended St. Augustine’s from 1883 to 1887 and Oberlin College from 1887 to 1889. He took art classes at the Art Students League in New York and the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts).

He worked as a draftsman and designer at the Hirst Smyrna Rug Manufacturing Company in Vineland, NJ; and Marcus Bros. glass works and Oesterle in Philadelphia.

In 1895, two of Dillon’s watercolors and a portrait study were shown in the Negro Building at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. In a newspaper article, he was mentioned as a stained-glass designer for one of the largest companies in the country (the company was not named). Dillon, painter Henry Ossawa Tanner and sculptor Edmonia Lewis were singled out for praise in the article, which denigrated the totality of works by African American artists.

Dillon’s work as a fine artist and stained-glass designer was noted by newspapers at several stops of the 1929 Harmon Foundation traveling exhibit of African American artists. This was Dillon’s first submission to Harmon, according to the 1989 catalog “Against the Odds: African-American Artists and the Harmon Foundation,” which accompanied an exhibit at The Newark Museum. He received an honorable mention.

The Harmon Foundation was among the first to hold monetary award competitions and exhibitions for Black artists starting in the 1920s. Dillon worked in watercolor and oils, and produced landscapes, still lifes and portraits.

In New York, the first stop, the New York Age reported that offers had been made for works by Dillon and several other artists. “One striking fact was the enthusiasm of the purchasers,” the newspaper noted.

In Atlanta at the YMCA, the Atlanta Constitution noted his work as a stained-glass designer, along with the full-time jobs of some of the others. The exhibit showed “the remarkable story of ambition, struggle and ultimate achievement found in the lives of the exhibitors. … Most of the exhibitors are making their living in other ways and pursuing art as a sideline,” the article stated.

In Louisville, KY, the Courier-Journal mentioned his still-life paintings: “The Still Life of Frank J. Dillon shows the influence of practice with stained glass and the big blue dish has the quality more of an enamel. His ‘Christ Blessing Little Children’ reminds somewhat of the less stormy windows by Kent in the English churches.”

Dillon also exhibited in the Harmon show in 1933.

He participated in group shows at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton in 1935, the Harmon College Art Association Traveling Exhibition in 1934-1935 and Harmon Traveling Exhibition in 1935-1936. In another Harmon-affiliated show, he was represented at the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey in 1946. He also exhibited at the Library of Congress in 1940-41, according to the “Against the Odds” catalog.

Dillon died in 1954.

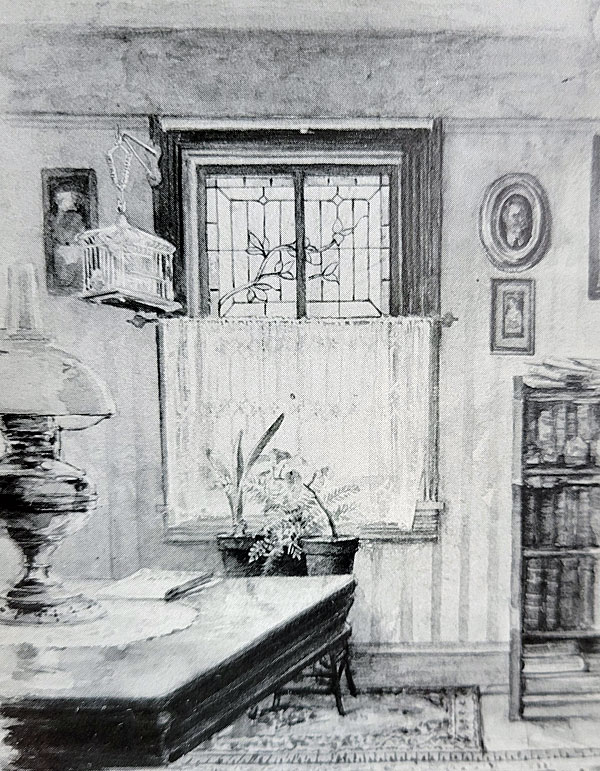

One of the stained-glass windows at auction had hung in Dillon’s home. He painted a watercolor of a room in his home with the window, which was created around 1910, according to catalog for an exhibit titled “Philadelphia African Americans: Color, Class and Style 1840-1940” at the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies in 1988.

Here are samples of the miniature stained-glass designs donated by Oesterle to the library:

Enjoyed this article… interesting to learn about serious artists with day jobs in other fields. I especially like the stained glass with the green vines. Beautiful!