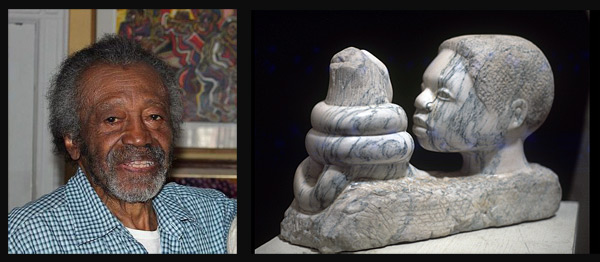

Otto Neals was born with talent, but he never stopped pushing himself.

He mastered watercolor after years of trying. “Watercolor was very difficult for me. But I loved it so much that I kept going at it and that’s one of my favorite mediums now.”

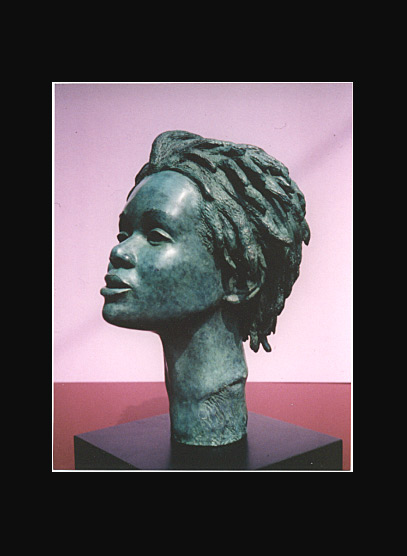

He talked for months about stone-carving with artist Vivian Schuyler Key in their Brooklyn, NY, studios. One day he found cutting tools on his desk. “I said to Mrs. Key, ‘So you’re showing off. You’re going to start carving in stone.’ She said, ‘No, No, enough talk. These are for you.’ So that’s the start of my carving in stone.”

As a 16-year-old in the 1940s, he bravely sent copied cartoons to two of his favorite newspaper cartoonists: Milton Caniff and Al Capp. “Milton Caniff sent me two original drawings of Steve Canyon and Copper Calhoun, two characters from ‘Steve Canyon,'” he says. Capp sent him a reproduced “Li’l Abner” comic strip and a thank-you note.

Today, at age 90, Neals is still at it. Over the last year during the pandemic, he produced about 20 collages. In addition to watercolors, he also works in acrylics, pastels and oils, and creates sculptures in bronze, wood, clay and stone – sometimes with found materials.

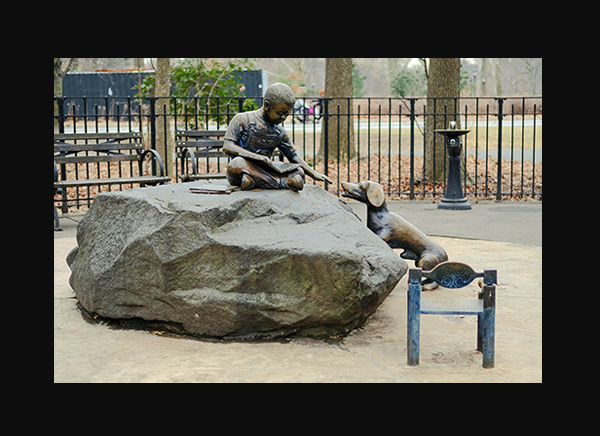

A piece of marble on the sidewalk turned into his first stone sculpture, titled “Curiosity” around the mid-1970s. His “Young General Moses,” a favorite that is a tribute to Harriet Tubman, was carved from a piece of maple he also found on the sidewalk. The foundation for a commissioned bronze of “Peter and Willie” is a huge boulder dug up during construction in Prospect Park in Brooklyn, site of the sculpture. It was based on characters from author Ezra Jack Keats’ books.

A sense of purpose in his life and works

“I believe it’s something spiritual, mystical,” he says about his artistic ability. “I’m untaught, self-taught, except for a month or two at the Brooklyn Museum with Isaac Soyer and printmaking at the Bob Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. That’s the only training I ever had.”

Neals is one of those wonderfully talented artists who emerged during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s at a time when they were not accepted into the mainstream as readily as they are today. Most recently, two sculptures he created were sold at the Black Art Auction’s November sale. “Young Nanny of the Maroons” went for $13,750 and “P.S. I Love You” sold for $7,500.

He was a member of the Weusi Artist Collective in Harlem and co-founder of its Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery. In the 1960s, Weusi, Spiral – organized by Romare Bearden and some of the most well-known artists of that time – and AfriCOBRA in Chicago were among the groups formed to promulgate the excellence of Black artists and their subjects, and to exhibit their works.

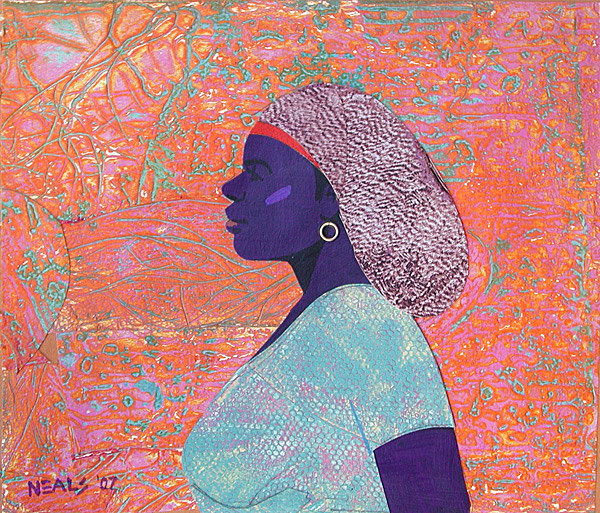

Neals was attracted to Caniff’s cartoons, he says, because his characters were realistic. He has done the same in his artwork, whose images are of real Black people – whether on canvas or prints, in stone or bronze.

“I try to present images of Black people in majestic poses and uplifting poses to overcome some of the shortcomings we’ve experienced as far as imagery when it comes to us,” Neals explains.

“A young girl I met when I was traveling in Dominica, she just gave off a wonderful spirit. Using photographs and memory, I created a piece I call ‘Tomorrow’s Choice,’ and I created it in bronze. Unfortunately, I did a small edition – I think about six or seven pieces – and people gobbled them up. I think I managed to save one piece.”

First the South, then Brooklyn

Neals was born in 1930 in Lake City, SC, the same small town where astronaut Ronald McNair was born, as Neals points out. His mother Mudell, known as Della, moved to New York to find work while Neals, his father Gus and his sister remained in Lake City. The entire family moved to Brooklyn when Neals was four years old. He still lives there.

His parents bought him an oil-painting set when he was 13, and he began copying the works of the old masters, including Rembrandt. He also copied “Steve Canyon” cartoons from the New York Daily News, and painted a full-page Sunday colored panel that he says he still has.

That’s when he sent those drawings to Caniff and Capp, and got responses from them. “I was really moved,” he says. “All my life I’d had them (their pieces). Up until a year ago I found that they were missing. … I think somebody pilfered them. I used to show them off quite often. They’re not in the space where they used to be.”

For years, his first recollection of drawing was watching his cousin David, who cared for him while his parents worked in the fields in Lake City. “I can recall watching him draw and pictured myself copying the drawing. But I found out later that wasn’t true at all.

“I think there was something mystical, spiritual that took place because he never drew. This is all recorded in a book by Elton Fax, ‘Black Artists of the New Generation,’ in which I mention the same story. (David) worked up in New York and when he retired, he went back to the South. I think one of my aunts passed and I went down to visit and I went by to see him and while I was there I presented him with this book.

“And I said look there’s a part in here about you. ‘David Neals was the influence behind my ability to draw and paint.’ And he said, ‘What are you talking about? I never drew.’ All my life I believed that he was the influence. I pictured myself watching him drawing but he never did. It was probably a dream and I took it to be real and I built on that.”

Working at the Post Office

Being an artist was not a sustainable occupation for Neals. He paid the bills by working at the General Post Office in Brooklyn. He started there in 1951 and stayed for a year before going into the military. When he came of draft age, he decided that he didn’t want to join the Army.

“So I went down to join the Air Force and they said, ‘Where’s your birth certificate?’ I said, ‘I don’t have one. I was born in the South. They weren’t too crazy about issuing birth certificates for people like me during those times.’ So they said, ‘Sorry, you can’t join.’

“But I was drafted into the U.S. Army without the birth certificate. It’s insane.”

Neals says his parents told him that he was born in 1930, but he says he saw somewhere that he was born in 1931 (Articles about him use both years). “I believe it’s 1930,” says Neals, whose birthdate is Dec. 11. U.S. Census records from April 1940 list him as nine years old and his birth year as 1931. A U.S. military record shows his birthdate as Dec. 11, 1931.

While in the Army, he created posters and signs, and for free, painted family members for soldiers. After two years, he was discharged as a sergeant, he says, and returned to the Post Office as a clerk.

Neals learned that the Post Office had an art department, so he applied and passed the test. He waited and waited to be called. Others were assigned to the department but not him. Finally, he went to the white postal union, where he was met with more delays, and then the Black postal union, where he was finally able to break through the logjam.

“The Post Office didn’t want to be accused of discrimination, so they put me in the art department,” he says. He started out as a sign painter and eventually became an illustrator.

Around the time of the U.S. Bicentennial, he created a 4-foot-by-8-foot wood relief sculpture of the “Spirit of 76” that hung in the lobby of the General Post Office. In 1999, the building was purchased and then renovated by the federal government for the U.S. Bankruptcy Court and offices. The General Post Office is attached to it.

Neals says he was told that the sculpture was tossed in the dumpster. It was apparently retrieved, put in a corner for a few years and now hangs in the employees’ cafeteria in the Post Office, according to Neals. He says he had asked one postmaster that it be donated to the Brooklyn Historical Society if the Post Office no longer wanted it.

“I don’t know if it made its way back to a dumpster or what,” he says. “Maybe one day, I’ll get up to see if it’s in the employees’ cafeteria.”

When he retired in the late 1980s after 36 years at the Post Office, he was head illustrator.

Weusi Artist Collective, 1960s

Neals was a co-founder of Weusi, which grew out of a split among artists in Twentieth Century Creators co-founded by artist James Sneed.

“It went well for awhile. There were other artists with pretty strong personalities who challenged Sneed about something, and the group broke into two parts,” recalls Neals. “One part remained the Twentieth Century Creators, but the bulk of them fell away and became the Weusi artists. I became one of those who went with that group. Five of us from that group founded the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery, which means the ‘House of Art’ in Swahili.”

Neals, Abdullah Aziz, G. Falcon Beazer, Taiwo Shabazz and Rudy Irwin founded the gallery not long after Weusi was formed around 1965. Weusi had two women artists, Kay Brown and Dindga McCannon. They were among the Black female artists who met in the late 1960s to form the female collective Where We At.

“We wanted to present the works of black people in a positive way,” Neals says of Weusi. Several Weusi artists built sets and worked with the New Lafayette Theatre – including Bill Howell and James Sepyo, he adds.

“When we had problems paying the rent, we even got help from some of the actors that were there.” Among them were Whitman Mayo, who in the 1970s played Grady, the friend of Redd Foxx’s Fred Sanford on the TV show “Sanford and Son.” Another was Carl Gordon, who played the father Pop on the 1990s TV show “Roc.”

About a year after a violent rainstorm flooded the second-floor gallery, it was moved to a space near the Lincoln Center.

Weusi held art exhibits at East Coast colleges, the Studio Museum of Harlem, among other places. The group is still around and periodically sponsors exhibits but has no gallery. Neals was represented for the last 40 years by Dorsey’s Art Gallery in Brooklyn, whose owner was a mentor for and promoter of Black artists. Lawrence Peter Dorsey opened a frame shop in 1970, and the place eventually became an art gallery that hosted major exhibitions and catered to collectors. Since Dorsey died in 2007, Neals says that he and other artists have kept it open.

What he’s creating now

Neals works out of a studio in his basement, surrounded by tons of artwork, tools and materials. He has more works in his attic and garage. For 1 ½ years, the Joan Mitchell Foundation sent two people who catalogued 2,500 of his works, and he was tasked with completing the documentation. It’s still on his list of things to do.

“I haven’t been as good a student as they’d hoped,” he says.

Cataloguing art isn’t as much fun as producing it. Neals has spent the last year creating collages from his own works. He starts with a collagraph, which involves layering found materials – lace, buttons, keys, zippers, string, anything flat – and ink on a board and then running it through a press to make a print.

“My collages are quite different from other collages,” he says. “Most of the collages, they use magazines and cutouts from other printed materials. My collages are made up of materials and textures that I’ve created myself in printmaking.”

He uses his discarded collagraphs to make his collages. “Those that didn’t come out too good, I toss aside,” he says, “Then I’d look at them and say, ‘Hey, I can use this.’ And then I’d start making my collages. I started by cutting up those (collagraphs).”

A brilliant saxophonist? Or not?

Although art is his heart, Neals also had an interest in music. At one point, he got a reputation as a great jazz saxophonist, a label that he says was undeserving. While in high school, he was invited to play with classmate Clarence “Scoby” Stroman, who went on to become a distinguished drummer, and others at a dance.

“We used to fool around and play, and for some reason they thought I could play. So they invited me. I’m young and stupid, so I show up at the place in downtown Brooklyn.

“I’m up there making some noise with the group. Then someone said, ‘Otto, you solo.’ I say, ‘What?’ So there’s one song I used to fool around with a lot by one of the old saxophonists Hal Singer. It went like:

“Then they start making noise and because Scoby Stroman and the others in the background they were so good, they created a sound, a movement. The crowd got excited and they (said), ‘Blow Otto blow,’ and I take my cue from them.

‘I didn’t know what I was doing. I was just making noise, and from that Scoby Stroman started telling all these people, including Randy Weston, that I could play a horn. I had Roland Alexander, another fantastic saxophonist, come up to me one day and say, ‘Man, I heard you play some bad horn.’ This was because of Scoby telling all these people. I had no idea what I was doing. I was there making some noise and it fooled the people.”

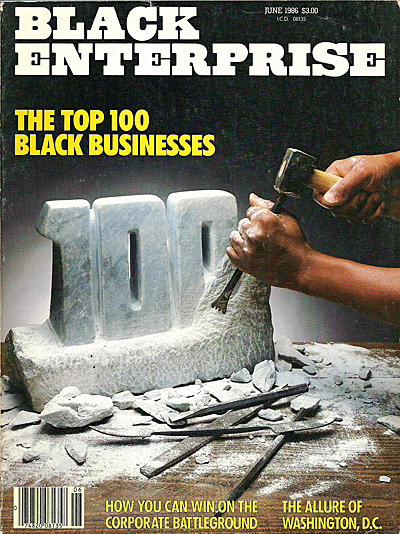

The cover of Black Enterprise magazine, 1986

Neals isn’t much into fooling people; his art speaks the truth. Maybe that’s why he scoffed at a request stemming from a commission from Black Enterprise magazine. Editor and Publisher Earl G. Graves asked him to create a stone carving for the cover of the June 1986 edition featuring the top 100 Black businesses, he says. Graves wanted the number “100” carved in stone.

“They wanted me to pose with the piece,” he says. “They wanted me to bring in my tools and some of the marble dust. Also the secretary told me Mr. Graves made an (appointment) for me to go to his manicurist to have my nails manicured. I said, ‘No way. If anything, my hands should be filthy and dirty.’ He wanted my nails manicured for the cover.”

The actual cover shows a pair of hands dusted in stone. “The photographer took my hands as they were,” says Neals.

This article warms my heart. To my great uncle Otto I am blessed to have met you at the ripe age of 80. To have living proof where my artistic gifts are rooted is a blessing all in itself. Sharing your works and words with my children, 4 generations, is humbling. It also gives them light into why their hands are gifted too. We love you and continue to with you many blessings and good health.

Hi Sherry, Great article and timely too!!!! “Young Nanny of the Maroons” was my last major purchase of a bronze sculpture at auction. I visited Otto at his home in 2007 in hopes of acquiring one of his bronze busts. Unfortunately, other purchase opportunities surfaced following my visit that were better fits for my art collection. I always regretted not purchasing “Tomorrow’s Choice.” I recall seeing “Young Nanny of the Maroons” during my visit, but if remember correctly Otto said the sculpture was not for sale because it was special to him. When I saw the edition of this sculpture featured at the Black Art Auction, I knew it was meant for me.

Hi Brinson, it was a joy to interview Otto Neals. I’m assuming that you were able to purchase “Maroons.” Good for you. It’s a lovely sculpture.

Thanks again for your article on Otto Neals. It motivated me to reach out to him via phone for a brief discussion on the work I recently purchased and other works that I have admired over the years. I also purchased your book via Amazon. I can’t wait to read it!

Thanks, Mike.

Otto Neals is an underappreciated national treasure! A master of multiple mediums including painting, printmaking and sculpture, Otto has always been able to capture the African American experience with dignity. Bravo for bring this unsung visual griot to light.