As a child, Gertrude Ann Graves had difficulty expressing herself. She stuttered. She wasn’t as lovely as her sister, whom relatives gushed over. She was a quiet girl who retreated to an apple tree on a hill behind her house when she was sad.

In kindergarten, she discovered the magic of drawing. On that first day of school, the teacher gave her some crayons to soothe away her tears after her mother dropped her off.

“That has been my go-to for peace and comfort in my life,” said artist Ann Tanksley, now 86. “It has just been the one thing that has given me a voice. As a child I stuttered. I didn’t speak well, so I could draw and say what I wanted to say. And over the years, I’ve learned to develop the process so I could better say it through education, through traveling, through just many things.

“My voice is in my painting.”

Tanksley is a painter, printmaker and collage artist. She works in watercolor. She paints in oil. She processes in black ink. Her works are in museums and private collections. She is a versatile artist who has been at it for more than 60 years, but some folks have probably never heard of her.

I was introduced to her work some years ago at the Sragow Gallery in New York when I was searching for prints by African American artist Elizabeth Catlett. Those were the days before the internet was ubiquitous, so it was difficult to find information about many Black artists who were not named Catlett or Romare Bearden or Jacob Lawrence.

Tanksley receded into my memory, and I hardly heard anything about her. Unfortunately, none of her works ended up at the mom-and-pop auctions I attended, so I was never able to acquire any. Over the past decade, her privately owned oils and prints have turned up at major auctions, several this year.

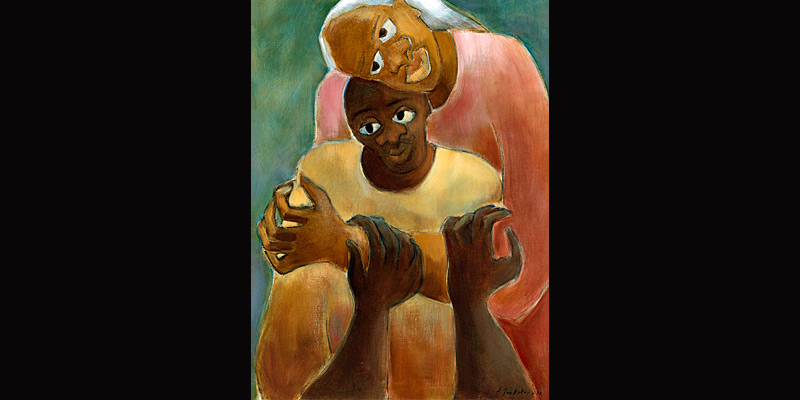

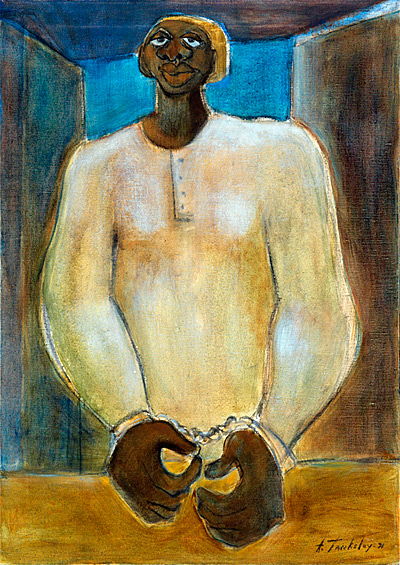

In January, two of her oil paintings were sold at Swann Auction Galleries in New York as part of the Johnson Publishing Company collection. “The Smothering Mother (1971)” sold for $16,250 (including a 25 percent buyer’s premium). “Imprisoned (1971)” sold for $22,500 with premium. Others of her works at various auction houses have fetched much less.

Both are lovely paintings in themselves. But the prices may have been driven by the traditional art market’s emergent interest in African American artists, several of whose works have brought in big bucks. These included veteran artists Catlett, Charles White, Norman Lewis and Barkley Hendricks, and contemporaries Kerry James Marshall and Kehinde Wiley. Slowly, museums and collectors are making room in their collections for the missing pieces of art history that are African American-derived.

Tanksley is hoping to get more of her own works into the market. She says her house resembles a gallery, with two studios and a storage room filled with hundreds of oils, prints and collages. She also has a collection of works by other artists, including members of the Weusi Artists Collective, founded in the 1960s. She has begun cataloging all of it.

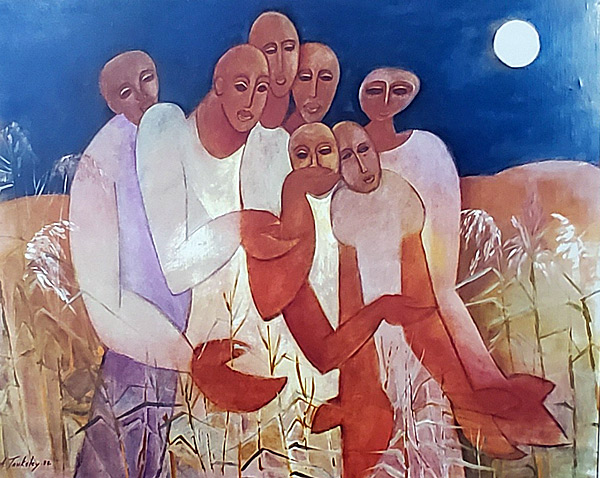

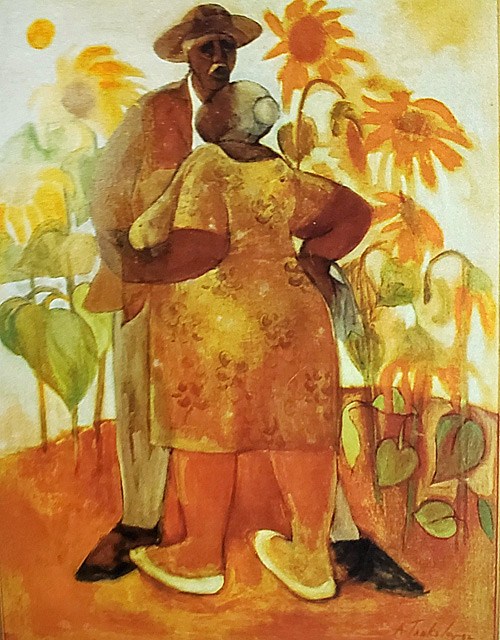

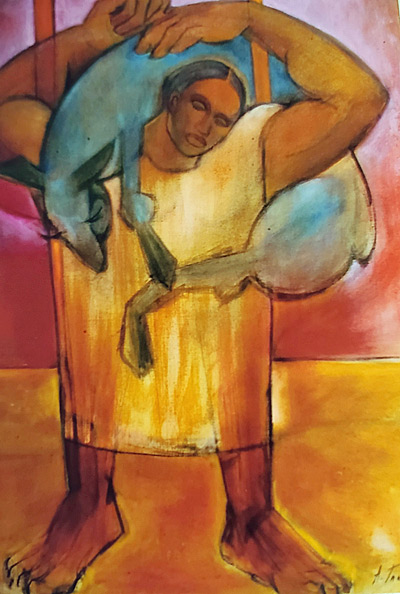

Her repertoire of mediums and subjects is varied. Her robust human figures have a familial and familiar feel to them. Many tend to have noticeable features: piercing eyes, and oversized hands and feet. “It’s seeing,” she said. “That’s what (the eyes) represent.

“The feet represent earth because when I was a little girl, I was in my bare feet and I loved the earth,” said Tanksley, an avid gardener. “It’s the spreading of the toes and the comfort and the balance.”

Inspiration for her works

Her works grow out of something she has read, something she has seen or something she has heard. She absorbed the jazz that permeated her hometown of Pittsburgh, PA, and recreated the music in paintings of jazz performers, including Thelonious Monk. She did a series on kimonos after Monk returned from Japan in 1963 and brought some back to the States with him, Tanksley said. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, she produced 36 canvases measuring 12-by-12 inches titled “Homage to Katrina.”

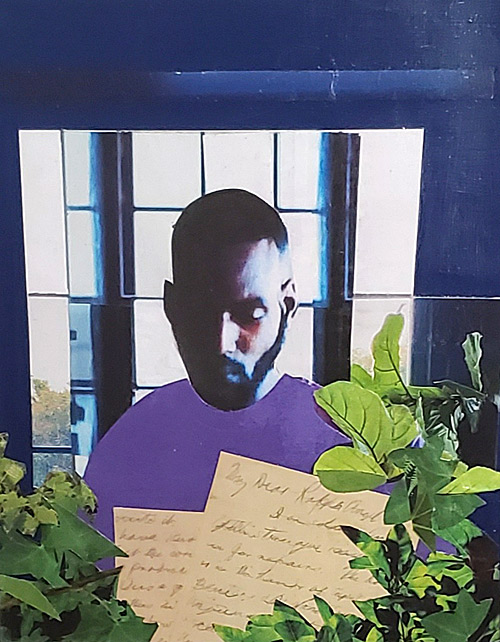

Recently, she completed 20 collages based on “Queen Sugar,” a show on Oprah Winfrey’s OWN network that she watched weekly as she stayed near the bedside of her ill husband artist John Tanksley. He died this summer. Tanksley says she’s in the process of framing the collages and getting them ready for presentation.

“They are really quite wonderful,” she said. “I wasn’t physically able to go into my studio and paint, so this was an easy way for me to record it by watching the TV. … I love that show. I think the acting was superb, the cinematography. It really spoke to me in so many ways.”

One of her most notable accomplishments is a series she produced in the 1980s based on the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, a Harlem Renaissance author of books, plays, folktales and short stories. Tanksley and her psychiatrist-friend, Dr. Hugh F. Butts, collaborated on a book in which he would psychoanalyze Hurston through her writings and Tanksley would provide the illustrations. The book was never published, she said, but her works were featured in a solo exhibition.

First, she read all of Hurston’s books. And within the writer’s life and stories, she felt a kinship.

“I found that there was just a similarity in the two of us,” said Tanksley. “She had a sister who she looked up to and who was beautiful and wonderful, and I had the same type of situation. When I was sad, I would climb up into a tree to get comfort and she had her Chinaberry tree.

“We both had a need to travel. We both ended up in New York. I finally read her last book. I think it was ‘Barracoon.’ There was another book that recently came out and I found she did a lot of work in Pittsburgh, which is my hometown.” (Hurston wrote articles for the Pittsburgh Courier, the city’s black newspaper, in 1952 and 1953.)

Tanksley’s “comfort tree” was an apple tree, which eventually evolved into a work titled “Out on a Limb.”

Starting in 1988, she created 268 prints over eight years for the Hurston project, titled “Images of Zora.” The first 60 prints were exhibited in 1991 and 1992 in places familiar to Hurston – including Eatonville, FL, where she was born, and Morgan State University, where she attended the college’s high school division. Some were shown in 2009 at Avisca Fine Art Gallery in Marietta, GA, her primary gallery, and most recently near her home in Great Neck, NY, to where she and her husband moved in 1971.

Around 2006, she was asked to illustrate her first children’s book, “Six Fools.” It is a funny folktale adapted from a story collected by Hurston during the years she spent traveling through the South collecting “Negro” folktales. Tanksley has also illustrated several others.

Growing up and becoming an artist

She was born in Pittsburgh in 1934, one of four children (one child died in childbirth) to Gertrude and Marion Butler Graves. Her mother sewed for wealthy families in town, and her father was chauffeur for two mayors of Pittsburgh.

When she was in first grade, her parents sent her to speech therapy to help her overcome stuttering. As a child, she says, she always had a “thirst for learning.”

“Reading was absolutely necessary in our home,” she said. “Every Saturday after we did our chores, my mother allowed us to go to the public library, which was two miles away. We would go there every Saturday, pick up our load of books. She’d give us enough money to buy custard, which we would lick very cautiously as we walked home to make it last as long as possible. But those books we read all week, and the following Saturday we went back for another load of books.”

That first day in kindergarten marked the path to her becoming an artist. In high school, her teachers allowed her to present through her drawings. She attended Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), graduating with a degree in painting and design. She and John, who was attending the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, got married after she graduated. Then they moved to New York, settling first in Brooklyn in 1957.

Tanksley needed a job, so she became a recreational therapist at Elmhurst General Hospital and taught the same subject at Suffolk County Community College. She was also a substitute teacher in the public schools. John Tanksley worked in advertising art and eventually opened his own studio retouching photos for major advertisers, she said.

He was also the primary money-maker. “It was not my objective to make money, although I did want to sell my work,” said Tanksley. “My art came through healing and giving me an opportunity and an outlet. It was always my go-to place for comfort and solace.”

She took writing and printmaking courses at the New School for Social Research in New York, where she met artist Otto Neals. He suggested that printmaking was an easier way for her to sell her paintings. He directed her to the studio of Robert Blackburn, a master printmaker and artist, who with Neals guided her in the craft, she said.

Tanksley was living in New York during the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s when Black artists unabashedly focused on their own culture. She exhibited with Weusi and was a member of Where We At, a Black women’s collective that included Faith Ringgold, Dindga McCannon and Kay Brown.

“It was during a very trying time,” she said. “I pretty much put into my paintings all the experiences, the racial discrimination, the things that a young woman has to go through in growing up. Some of it was very angry and very hostile and very mean, but it gave me a chance to vent.”

One of the things she remembered was a childhood friendship with a white girl in her mixed neighborhood in Pittsburgh. The little girl had a party and did not invite Tanksley, who was hurt. Crying, she asked her mother why. “She said, ‘Oh honey, I’m sure she had nothing to do with it.'”

The exclusion didn’t change in college – she was the only Black person in her class – where whites who had befriended her in their neighborhood joined sororities and fraternities that barred her. She found inclusion, she said, in the “LGB community because they were also being separated and excluded.”

In New York, she exhibited with Acts of Art Gallery owned by Black artist Nigel L. Jackson. She was also among the African American artists who participated in a show in response to a Whitney Museum of American Art exhibit in 1971. Titled “Rebuttal to the Whitney Museum Exhibition,” it was mounted by artists angered by Whitney’s failure to engage Black artists and hire a Black curator in its exhibit of contemporary Black artists.

When Tanksley was at Carnegie, she said, one of her teachers pointed out every day to the class that she would have a hard time making it as an artist. The reason, though he never mouthed it, was because she was Black. His prophecy was not entirely correct, she says.

“I’ve been blessed. I’ve been able to show my work,” said Tanksley. “People have been kind enough to invite me into what they were sharing. It is hard. I did one piece called ‘Women’s Lib.’ The images were white chickens. I used my chickens to make a statement.”

Inspired by her international travels

Her first foreign trip was in 1977 to Africa, followed over the years by Haiti, Brazil and Qatar right after 9-11 to teach printmaking. When she returned home, she produced at least 100 paintings from each trip, she said.

“I believe in genetic memory because many of the things I had painted I saw firsthand in Africa,” said Tanksley. “I know this may sound weird, but this is about my genetic connection with Africa. When I was a little girl in kindergarten, they brought a cow to the playground. The kindergarten students were to go out and help milk the cow, which was a big experience. … Then we sat around a circle in the room and we shook the bottle to make butter. That had such a deep impression on me for some reason. Fast forward, I go to Africa. One of the most prominent animals there was the cow.

“And it was just like it was a foretelling of something that was going to connect (to me) later in life. I could feel there are all these connections. I think everything is divinely designed. I think God has a plan for everything. If you listen to Him, He’ll tell you what to do, when to do it and how to do it, and help you along.”

She was raised a Presbyterian and her husband, a Baptist. She says she loved going to his church services, from which she drew ideas from his minister, a powerful speaker. She witnessed voodoo ceremonies in Haiti, learned about candomblé in Brazil and was able to “visualize and experience the (Muslim) faith” in Qatar.

“There came a point in my life where I wanted to do two things: I had been born and raised in the Presbyterian church and I wanted to know more about my religion. I wanted to know more about the Black man and his religion, and with that I began traveling so that I could actually see the process that was taking place.”

Biblical references are present in several of her works, including “Come My Yoke is Easy.” Over the last year, she completed a collage titled “Ritual,” about various religious rituals.

“Every work that I’ve done represents some phase or some part of my life,” she said. “I never had great self-confidence. But this was some place where I could go and be happy, and receive the love. I could understand and accept myself.”