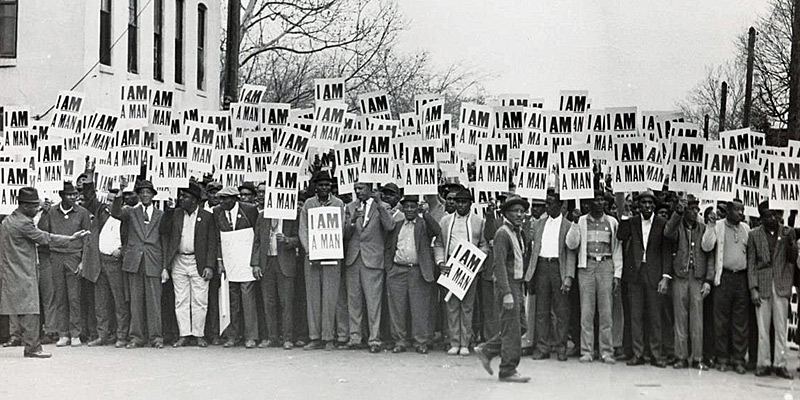

In March 1968, striking black sanitation workers marched along the streets of Memphis demanding higher wages and better working conditions. They carried signs emblazoned with “I AM A MAN” to express their anger at not being treated humanely. Along the march route, they fought with a mob.

The morning after, someone picked up one of the signs that had been dropped on the street. More than 50 years later, that iconic sign sold for $23,750 at an auction in New York.

The price of the sign was significant, but what was more important was what it represented. It was a marker for a period in the country’s history when African Americans collectively said “Enough!” These black men asserted their manhood with those four simple words of affirmation.

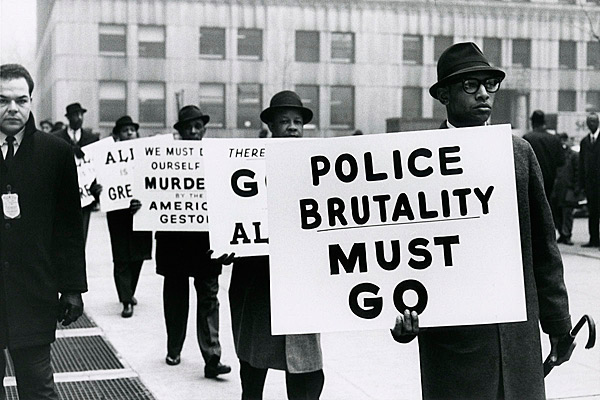

They were just one group of the thousands of people – most of them black – who marched, were beaten, spit on and jailed to protest segregation, discrimination, police brutality and a country built on hatred of them.

Those scenes of protest are replaying now across this country and the world. Police brutality in the lynching of George Floyd ignited people who would normally be immune to these transgressions. Hundreds of thousands of them – black and white, of all ethnicities, in countries where people would rarely meet a black person – have taken over the streets.

They speak for those who have been silenced: Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks and all the other black people who were killed by police officers.

The “I AM A MAN” poster was one of several 1960s artifacts that I’ve seen at auction over the years. Every time, I’m reminded of the importance of documenting and maintaining the items that tell the full history of this country.

What will be the artifacts from the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020? Should we be saving them for their monetary value for our children and grandchildren? Or should we keep them as historical documentation of this period?

What artifacts do you think will represent the 2020 protests?

If you plan to hold on to artifacts for posterity, it’s important to remember that all are not monetarily valuable. Regardless, they should be kept as mementos of what could be a revolutionary period in the country’s history.

Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture and now secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, urged museums to “collect this moment. To make sure that this history, that the visual history of this, is collected so that we can tell the story now, but I would argue is going to be a crucial story to understand in 50 years.”

Since 2015, the museum has been collecting photographs, posters and other artifacts pertaining to the Black Lives Matter movement. It has also been accepting videos from protesters.

Some of the artifacts from the 1960s and 2020 are similar: photos of raised and clenched fists; police in riot gear (this time with tanks); protesters with signs, banners, posters (most handmade in 2020, some professionally printed in 1960s) of the most important issues of that period.

But there is also a major difference: Phone-camera videos are very important in collecting history of the now, as well as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and other digital methods. How do we capture and save those for posterity?

The 1960s had its share of public figures, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Malcolm X, Newton and Eldridge Cleaver and the Black Panther Party, Dorothy Height and the National Council of Negro Women, Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Democratic Party in Mississippi, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), among others.

There’s much less of that this time around. The predominant organization is Black Lives Matter, which became prominent as protesters carried handmade signs bearing its name. The protests appear to be truly grassroots, unlike some of the orchestrated and planned strategy of the 1960s. Today’s protesters are demanding, rather than asking – more Black Panther than SCLC. They are primarily made up of young people, including white Americans and foreigners. They are more strident. They aren’t looking for handouts to appease them, but substantive changes that make blacks truly Americans.

1960s artifacts

Here are some artifacts from the 1960s. Others would include newspaper articles and photos:

- Banner linked to the origin of the Black Panther Party

The banner was made by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, founded in Alabama in 1965 with Stokely Carmichael as one of its organizers. The group adopted the panther as its emblem to counter the Democratic Party’s white chicken. It became known as the Black Panther Party. When Newton and Cleaver founded their party in Oakland, CA, they picked up both the name and the emblem.

- Protest signs, a sampling: “We Demand an End to Police Brutality Now,” “We March for Integrated Schools Now,” “We Demand Voting Rights Now,” “We Demand Decent Housing Now.”

- Letters/speeches/books/postcards and other ephemera by King and others

- Black Panther newspapers, posters, buttons & Emory Douglas artwork

- Right to vote posters

- “Colored” and “white” segregation signs

- Pin back buttons and banners

- Fountain pen used by President Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Bill in 1964

- March on Washington record album

From 2020:

- Protest signs and banners: “Justice for George Floyd,” “I Can’t Breathe,” “Black Lives Matter,” “No Justice, No Peace,” “Defund Police,” “Breonna Davis,” “Stop Killing Us.”

- Face masks derived from coronavirus pandemic, with face of George Floyd and “I Can’t Breathe.”

- Photos: protesters, police in riot gear, police military tanks, Confederate and other statues toppled, protesters taking a knee in the form of Colin Kaepernick’s denouncement of police brutality and racial injustice.

- Names of those killed and protest slogans hand-printed on American flags

- Black Lives Matter yard signs and pin back buttons