I bought the newspaper at auction two years ago, but I just couldn’t bring myself to write about its contents. The stories on the front page were too horrific, too graphic, too painful.

Every headline told a piece of the story of the lynching of George White in Wilmington, DE, in June 1903. More than 5,000 white men stormed the jail where he was being held, beat and brutalized him, dragged him to the place where he allegedly raped and killed a 17-year-old white girl, tied him to a stake, put straw and fence railings under him, lit them with a match, and knocked him back into the fire when he tried to escape.

People jostled and growled their way to the front to see for themselves a black man consumed by ugly flames – cheering his torment with cries of hatred.

After I got the newspaper home, I put it aside. It’s not easy to be placed in the thick of another person’s hell. I decided now to retrieve the newspaper in light of the murder of George Floyd, who wasn’t burned at the stake but was lynched as well. Not by a mob but a white police officer with the same hubris and inhumanity.

The newspaper bore a tiny faded address label with the owner’s name. I wondered why he or she had kept it. For a souvenir, as the people who picked through the ashes for parts of White’s body? Or as a reminder of such an ungodly act?

With today’s technology, we can easily record the brutalities. We watched as Floyd died facedown on a sidewalk with a white Minneapolis police officer’s knee (and body weight) on his neck and as Ahmaud Arbery staggered and dropped to the ground after being shot by white men in Georgia. White’s ordeal wasn’t captured on video, but newspapers recorded it in stark language. Very few people have even heard of him or the countless others whose lives were mercilessly taken by such insanity.

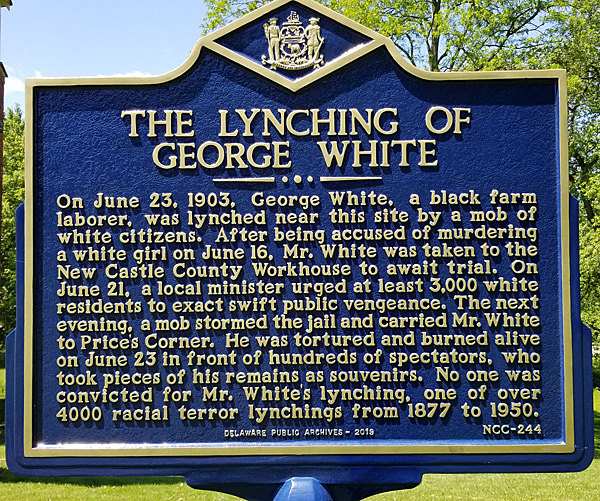

Some in Delaware want us to remember George White. A college student, Savannah Shepherd, spearheaded a project to have a state marker erected on the site of the lynching. It was installed in June 2019, stolen a few months later, and a new one erected in October. Also, a short documentary film was made in 2004 titled “In the Dead Fire’s Ashes: The Lynching a Town Forgot” by Stephen Labovsky.

I dropped by Greenbank Park in Wilmington Sunday to see the marker and the spot. A cool breeze slightly chilled the sunny day and rustled leaves on the park’s thicket of trees. Sitting on a bleacher outside a baseball field, I stared at the marker and tried to imagine the place it once was. I couldn’t.

It was peaceful now: Adults with children sat on a picnic bench on a hill near another baseball diamond. Two men chatted in fabric folding chairs in a concrete parking lot. These scenes along with the expanse of mowed green lawn and fully-leafed trees enveloping the marker belied what had happened in the early-morning hours of June 23, 1903. The words on the marker, though, made it real.

I assumed that no one marched or protested on behalf of White. Lynchings were meant to terrorize, and I figured this one had quieted black residents. I was wrong. That week, the Rev. Montrose W. Thornton led a march of black men in downtown Wilmington to protest the release of the only suspect in the case. They were attacked by white youths and arrested, although the whites were not. Thornton was a fiery civil rights activist who spoke out relentlessly against lynch mobs like the one that killed White.

The following Sunday, speaking from the pulpit of Bethel A.M.E. Church of Wilmington, he called white men “demon of the world’s races, a monster incarnate.” Defend yourselves, he told his parishioners.

“The negro is unsafe anywhere in this country,” he preached. “He is the open prey at all times of barbarians who know no restraint and will not be restrained. There is but one part left for the persecuted negro when charged with crime and when innocent. Be a law unto yourself. … Die in your tracks, perhaps drinking the blood of your pursuers.”

Newspapers across the country and abroad published articles about the lynching, which occurred not in the South but above the Mason Dixon line in a state where abolitionists had once opened their homes to enslaved Africans seeking freedom. A white Chicago newspaper reported four more murders that same month – in Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana and Alabama. Lynchings were so common in the early 20th century that the NAACP hung out a banner on its Manhattan office in New York every time a black person was reported lynched. Maybe the NAACP should rehang a banner today.

From 1882 to 1968, more than 4,000 people were lynched in this country, according to the NAACP. Of that number, nearly 73 percent were black (mostly men). Mississippi and Georgia had the highest number of lynchings. Those numbers represent the cases that were reported. We’ll never know if a missing son or grandson or brother ended up as one of those unrecorded statistics.

Writer, activist and scholar W.E.B. DuBois, editor of the NAACP’s The Crisis magazine, journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett and others agitated against murderous lynch mobs in the face of a government that looked the other way.

Billie Holiday in 1939 hauntingly sang against its horrors in “Strange Fruit,” written by a white Jewish teacher named Abel Meeropol. In 1935, the NAACP mounted “An Art Commentary on Lynching” featuring black and white artists at a New York gallery. The original gallery reneged, buckling under pressure from political, social and business concerns. Another gallery quickly stepped in. The exhibit was part of a campaign to force Congress to pass an anti-lynching bill introduced a year earlier.

Three years before White was killed, George Henry White had introduced a bill to criminalize lynching and subject the doers to capital punishment. The bill never made it out of the Judiciary Committee. The first anti-lynching legislation finally made it through Congress this year. White, who was apparently not related to the Delaware man, was the last remaining black representative elected during Reconstruction. There had been 22 of them.

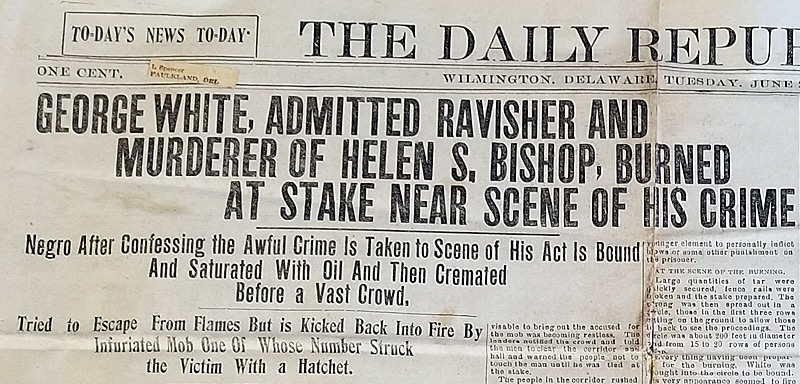

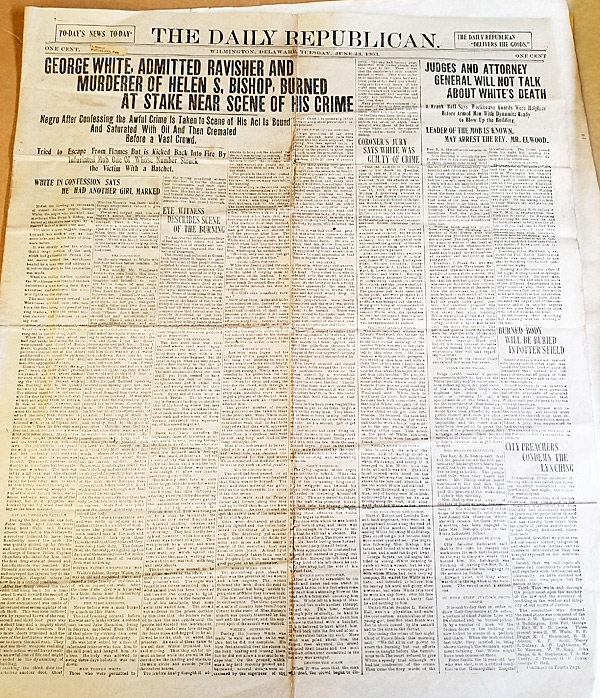

The newspaper I bought at auction was the Daily Republican, dated Tuesday, June 23, 1903. White was a farm laborer whose father George Sr. “was an old and respected slave and raised a large family of children all of whom turned out well,” according to the newspaper.

White had been charged with the death of the white girl, who was on her way home from school. The newspaper story claimed he had already confessed to the crime and recounted the details to the mob in his jail cell.

Here are some of those headlines:

“George White … Burned at Stake Near Scene of His Crime”

“Midst the howling of thousands of almost delirious people, George White, the negro who ravished and murdered Miss Helen S. Bishop, was burned at the stake last night by a frenzied mob of almost 5000 men.

“The scene almost beggars description and was such a one as has never been seen in the State of Delaware before. (This was not the first lynching in the state, just the first in the 20th century. This same article mentioned the lynching of Jake Hamilton in Smyrna, DE, in the early 1860s).”

“Eye Witness Describes Scene of the Burning”

“To describe the entire proceedings of last night is to relate the most harrowing tale of cruelty and barbarism that has disgraced the fair name of Delaware. …

“The dying agonies of the negro were terrible to behold. When the fire was lighted and he felt the first lick of the consuming tongues of fire he wriggled and twisted his … body and time and time again succeeded in throwing himself off the fire. This only served to infuriate the mob who promptly kicked him back into the blazing fagots.”

“Burned body will be buried in potter’s field”

“Souvenir seekers were not content with taking pieces of the rope that bound the lynched fiend or parts of the embers that burned him but many of them cut off pieces of flesh and toes and fingers and to-day exhibit the trophies. (In a similar case in Coatesville, PA, in 1911, whites returned to the scene for souvenirs after Zachariah Walker was lynched. White’s body parts were being sold around the city for $1 each.)

“Deputy Coroner Kilmer went to the scene to-day and secured what parts of the charred body that remained and took them to the morgue. … The charred remains were sent to the Potter’s Field at Farnhurst for interment.”

“City preachers condemn the lynching”

Several local ministers issued a statement, which read, in part:

“Resolved, first that we put on record our sincere sorrow, indignation and shame at the lawless and enthusiastic demonstration that has brought reproach on our commonwealth.

“Second, that we call upon all classes to condemn and repudiate such lawlessness and in humanity as has shocked not simply our own people but the nation at large.

“Third, That we in and through the pulpit insist upon the sanctity of the law and the necessity of confiding in the wisdom and integrity of our courts of Justice.”

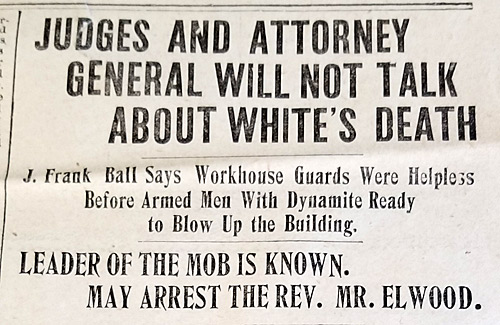

One person missing from the group was Rev. Robert A. Elwood who had called for the lynching in a sermon the Sunday before, and was chastised by some. His sermon had been advertised in a local newspaper, noting that Elwood would speak on the topic “Should the Murderer of Miss Bishop be Lynched” outside his church, Olivet Presbyterian Church at Fourth and Broome Streets. On that day, 3,000 people showed up.

The New Castle Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church found him guilty of inciting the lynching but offered no punishment. He was told to be more “judicious in his utterances.”

Here’s how he reportedly interpreted it:

“Finding of Presbytery: guilty; punishment, none; benediction: go thy way in peace.”

The newspaper (and others that wrote follow-up stories) noted that the lynching appeared to be well-planned. Arthur Corwell, a white man was charged with murder, but the charges were dropped to manslaughter after a crowd of 10,000 stood outside the police station to support him. His eventual trial was described as “farcical.”

Thank you for your courage to pull out the newspaper and share your thoughts. I was dreading reading about something you might mention about my uncle. At times I felt myself clenching my teeth and holding my breath. It is so tragic each and every time I realize that the blood which flows through my veins was once burned while it was flowing through Uncle Zachariah’s body. I am quite new to learning about my Great Uncle’s life and murder. It will be life long journey of healing and recovery and transforming our Lynching Legacy to one of Love.

There is still hope.

God bless!

Thank you, Shanda. It was a difficult blog post to write. I feel your pain. Sherry

Thanks for sharing this painful, yet relevant information, today lynching by rope has been replaced with death by knees or death by running, etc etc , death because you are born black .

Thank you for this history lesson which is so timely. 1903 to 2020, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

So true, so true.