Fashion shows have always been a mainstay in the African American community. Even now, they are still being held as fundraisers for sororities, clubs, churches and other organizations.

At auction a few years ago, I picked up a photo on cardboard of several black New York models from the 1950s. I wondered where the sponsors borrowed the clothes for them. In many places, especially the Jim Crow South, black women weren’t allowed to try on dresses before purchasing them, much less stroll around in them on an auditorium stage or down a church aisle.

So, black folks made their own way: Many of the models wore outfits made by local black designers, many of whom you may never have heard of. These designers worked in a world separate from the white mainstream from which they were barred, but they were important to the community where they lived.

In 1949, the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers (NAFAD) was formed to be an advocate for African Americans in the fashion field. Among its supporters was educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune and her organization, the National Council of Negro Women.

I first found the names of many of the designers while reading Hal DeWindt’s and other fashion columns in the New York Age newspaper from the 1950s. He wrote not only about gown-makers but also hat designers who were just as prominent. The New York Age, Jet, Ebony and other black publications – as well as black photographers – were instrumental in recording the history of the shows and people who produced them.

New York is and has always been the mecca for fashions in the United States, and Harlem seemed to be that place for black folks. While DeWindt focused on the black fashion industry in his town, the same was going on in other major cities.

“Thousands of black designers across America – some professional, some amateur – were a key element in a world of style and modernity against which black women shaped their identities, learned self-confidence and found myriad pleasures,” wrote Pat Kirkham and Shauna Stallworth in the 2000 book “Women Designers in the USA, 1900-2000.”

DeWindt filled his columns with details of the fashions shows and the models (which he sometimes called “manikins”), black modeling agencies and charm schools, and descriptions of the fashions and styles. A model himself, he was the first male to walk the runway for Ebony Fashion Fair (1959).

A designer who was very active during this period was Ann Lowe, who made gowns for rich socialites, including the dress worn by Jackie Bouvier when she wed John F. Kennedy in 1953.

Lowe apparently snubbed the community fashion shows; I never came across her name in any of the fashion roundups in several online copies of New York Age. At one point, though, Lowe herself was a writer for the newspaper, which is no longer being published.

“I love my clothes and I’m particular about who wears them,” Lowe said in an Ebony interview in December 1966. “I am not interested in sewing for café society or social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

Lowe was unknown to the “man-in-the-street,” Ebony noted. I suspect that many of the women who showed up at the Harlem fashion shows were not very familiar with her work. The names they knew were designers who got a “mention” in a column or a photo with a caption in Jet magazine.

Those “hidden” gems were always the ones who fascinated me. Many of them toiled in their own shops and other spaces assembling a collection that they could show off at weekend fashion shows, luncheons or their own annual shows in ballrooms and clubs.

They were making attire for middle-class black women who could pay $800 or more for an evening gown (Jackie paid $500 for her wedding dress, a steal. Many of Lowe’s upper-crust clientele paid less than her outfits were worth). The designers, some of whom were also models, produced these shows to attract clients and to raise money for worthy causes.

Here are some of those designers, several of whom were milliners. I could find little background info on most of them:

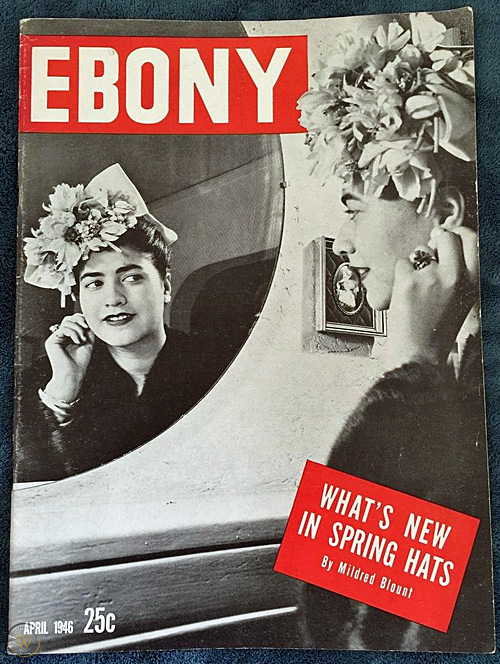

Milliner Mildred Blount

Blount designed miniature hat styles from the 17th to early 20th centuries for display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair – which got her noticed by the makers of “Gone With the Wind.” Working with her employer, the John-Fredericks Co, she helped make hats for the cast. Her clients included actresses Rosalind Russell (who invested in her company), Gloria Vanderbilt, Marian Anderson, Louise Beavers and Joan Crawford.

One of her hats was on the cover of Ladies Home Journal in 1942. She was featured in Ebony in April 1946, a year after the magazine was founded.

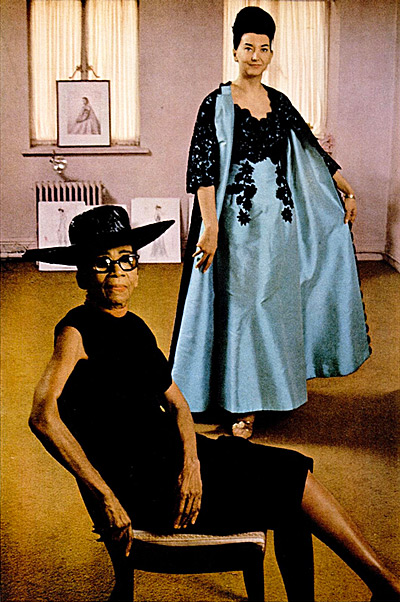

Designer Zelda Wynn Valdes

Valdes is cited in many online articles as the designer of the Playboy Bunny costume. But that may not be exactly true. She seems to have had a hand in it (at the request of Hugh Hefner) but she apparently was not the sole designer. She was the first black woman to open a boutique in Manhattan, in 1948. (In the photo at the top of the blog post, actress Joyce Bryant wears a Valdes gown.)

Valdes’ trademark designs were sexy low-cut gowns that hugged the body and accentuated a woman’s curves. Her clients included Dorothy Dandridge, Diahann Carroll, Josephine Baker, Marlene Dietrich, Mae West and Eartha Kitt. She was among the earliest members of NAFAD.

Designer Verlie Morrison

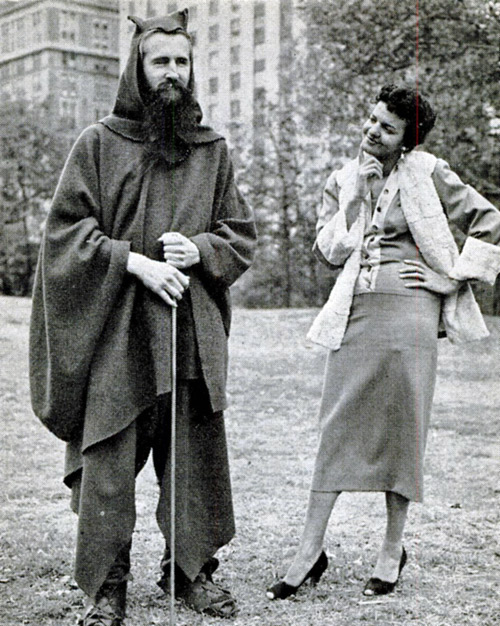

DeWindt mentioned Morrison, “an international stylist,” quite often in his columns, and she is mentioned a number of times in Jet magazine. She was born in Montreal and studied with French and Italian designers. She was always identified as “Canadian-born” in the articles.

Morrison’s fashions seemed to be a fixture at the Harlem fashion shows. She dressed Lena Horne and Sheila Guyse, a singer and actress who appeared mostly in so-called “race movies.”

In a Feb. 28, 1963 blurb in Jet: “Canadian-born designer Verlie Morrison has created a new group of stunning gowns for Lena Horne, several of which she will wear during her six-week engagement at the Waldorf Astoria’s Empire Room.”

Morrison was fitting Diahann Carroll for the designer’s winter show to benefit the NAACP Emmett Till Drive, according to an Oct. 22, 1955, article in New York Age. She was expected to present a 40-piece, $30,000 collection of gowns, furs and accessories, “the designer’s answer to the woman in constant search for clothes that are new and different.”

Emmett Till was a 14-year-old black teenager killed by white men in Money, MS, in September 1955 and his body mutilated. The murder mobilized African Americans, the NAACP and others who had not realized the brutality of Southern segregationists.

Here, Morrison models one of her gowns.

In an article in the Ohio Sentinel in 1958, Morrison was shown with a home economist for Pet Milk who was wearing an emerald green gown created by the designer. The dress was inspired by a new beverage made by the company.

The article appeared in several black newspapers around the country. It is not clear if Morrison was commissioned by the company to make the garment. The economist, Louise R. Prothro, was the one of the first African American women to be hired for a national position at a U.S. company.

Morrison often participated in fundraisers for the NAACP. At one event in 1954, she was shown in Jet magazine helping Horne into an $800 gown of Swiss satin and French lace that she later gave to the singer. At another NAACP benefit that year, she included a $750 white and gold gown among $8,000 worth of fashions. The gown was covered with 60,000 gold beads sewn by hand in clusters of 10. Esther Dorothy, a white furrier, provided $500,000 worth of fur accessories, including a $15,000 muff.

Milliner Milo Gough

Gough was one of the models in the photo I picked up at auction. She apparently was better known as a milliner. The original photo seemed to have been taken at one of her fashion shows. Each of the women wore a slender hat, presumably Gough’s designs.

A 1955 article in New York Age noted that Gough had studied with a French instructor named Andre Muzet (I found a hair stylist online with that name) for two years after taking design classes at local schools.

A blurb in Jet magazine mentioned a show at the Club Harlem featuring hats by Gough and outfits by Millicent Taylor, whose name appeared pretty often in the magazine.

Designer Milicent Taylor

Taylor was “wowing the East Coast in a red satin cocktail suit embellished with 82,000 sequins, all hand sewn, bead by bead,” Jet stated in its Nov. 5, 1953, issue. Taylor also created a pink silk evening dress and train from a sketch by designer Lowe. The dress is in the Black Fashion Museum Collection at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington.

In another Jet article earlier that year, she was identified as one of two Harlem seamstresses who worked 10 hours to hand-sew 100,000 bugle beads on a turquoise evening gown for her Palm Sunday fashion show. The gown was valued at $850 and the turquoise silk-satin coat at $400.

Designer Beulah Bullock

Bullock was known as “Mrs. B” or “Madame Bullock” because of her own fashion style and signature look.

“She was always coordinated from head to toe, everything matching, high heels and her signature turban!” according to her obituary. “You knew that was Madame Bullock as she glided through the streets of Harlem. Before there were reality designer shows there was Madame Bullock of Harlem.”

Bullock, who was born in Warrenton County, NC, died there in 2018 at age 105. She had lived in Harlem for 50 years before moving back to North Carolina. Bullock designed fashions for men and women during the Harlem Renaissance, and up until she was 95 years old.

“The annual shows of Beulah Bullock, New York top designer, always have demonstrated her prowess in the field of creative design, but styles recently modeled in the Hotel Diplomat’s Grand ballroom prove that, beyond doubt, the young woman’s flair for originality has soared to even new heights,” stated a fashion article in the May 1955 New York Age.

“The show was climaxed with a gown draping act in which the talented fingers of Beulah Bullock, using pins and yards and yards of lush fabrics, created gowns on models right on the spot, and at the phenomenal rate of one a minute. Guests left the show still wondering how the versatile lady could achieve such beauty with such speed and ease.”

A 1953 article in the Arizona Sun newspaper also noted her miraculous speed. “She can drape and finish a gown while the customer waits – a great time-saving for the girl who goes to business. She won first prize at one of the Harvest Moon Annual Balls in Madison Square Garden. The organization gave the award for a gown she fashioned out of 38 yards of heaven blue Chiffon and which was adorned with a host of 20-inch ostrich feathers evenly spaced over the whole skirt.”

“I am a lover of beauty,” Bullock said in the article, “and I enjoy expressing my ideals of beauty by creating materials into suits, gowns, dresses – any type of garment.”

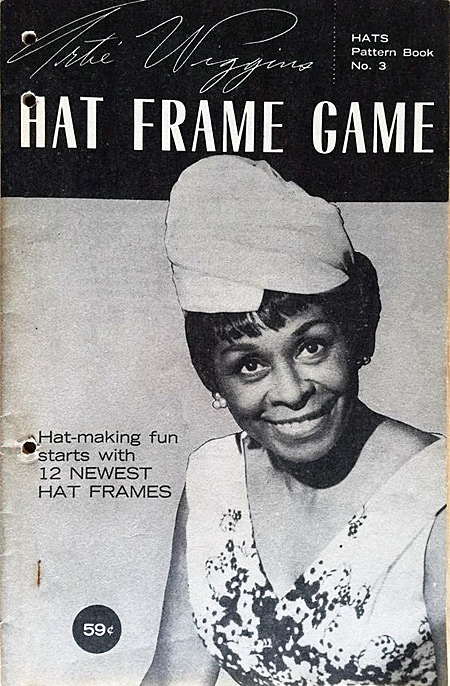

Milliner Artie Wiggins

Wiggins was a Chicago hat-maker whose name turned up often in New York Age and Jet. She was an author of two booklets on hats. She designed hats for Ebony Fashion Fair, as well as hats and patterns for Hats magazine. She also showed off her designs at fashion events in Chicago.

A photo and caption in Jet magazine in 1954 showed several of her hats from a show to benefit Israeli schoolchildren. In a 1964 Jet photo, Wiggins was shown wearing a designer suit she won for selling the most tickets in a Chicago Fashion Fair competition the year before. The design was a David Kidd for Arthur Jablow.

She was a close friend of Jackie Ormes, the first black female comic book illustrator who worked for the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier newspapers. Ormes used some of Wiggins’ hat designs in her “Torchy’s Togs” paper dolls.

Wiggins’ sister, Geneva Berrien, was a hat designer in Brooklyn. Her hats were shown in a spread with maternity wear in Tan magazine in January 1958. Like Ebony and Jet, Tan was published by Johnson Publishing Co.

Lois Alexander Lane

In 1963, Lane wanted to write her master’s thesis on black retailing in Manhattan. Her professor at New York University told her there was no such thing. The instructor was wrong. In 1982, Lane published a book titled “Blacks in the History of Fashion.”

In the interim, she opened shops in Washington and New York. Lane founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion in 1966 to teach African Americans how to design and opened the Black Fashion Museum in Harlem in 1979. The museum, which contained clothing, accessories and documents that she collected, is part of the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington. She was also a member and officer of NAFAD.

Other gown designers:

Ruby Bailey, was said to be an expressive person who was versatile in her tastes and styles. She also created portraitures and illustrations. She produced her own fashion shows and made costumes for theatrical productions.

Lois Bell, a designer and model. She was featured in a photo and blurb in a 1957 issue of Jet wearing a $500 lounge ensemble. She was repeatedly mentioned in New York Age’s fashion stories.

Willi “Madame Posey” Jones, mother of artist Faith Ringgold. Jones went into fashion designing after deciding against a career on the stage. She and several other designers – Barbara Mayo, Margaret Floyd and Bell – held their own fashion shows at the Waldorf Astoria in Midtown Manhattan and in Harlem to try to get major clients interested in their designs. She and her daughter made a quilt together in 1980 that they titled “Echoes of Harlem.”

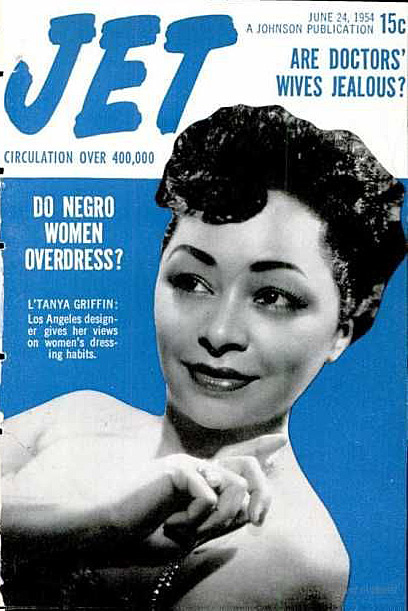

Bernice L. Tanya Griffin, known as L’Tanya Griffin, said to be one of the most well-known designers during the 1940s and 1950s.

Herbert Riley, described in New York Age as a designer.

Matiele Ria, a designer who had her own shop. She was also a singer and exotic dancer. A 1953 Jet blurb noted that she wanted to to save money to go to Paris to learn dress designing.

James P. McQuay, fur designer/manufacturer who offered his designs at fashion shows and whose ad for fur storage showed up in New York Age.

Other hat designers:

Juanita Scott, mentioned in Jet, 1954: “After being shacked up with velvets and velours for a month in Atlantic City, Harlem hat designer Juanita Scott delighted customers with a collection of chapeaux in shapes and shades borrowed from the sea. Her ‘lobster’ cap of sapphire blue has jeweled claws.”

Here’s a hat that Scott created for Gerri Major, woman’s editor of the New York Amsterdam News, for the 1952 Kentucky Derby. The designs on the hat and an ascot worn by Major mimicked newspaper sports pages and headlines.

Cleo Sims, got a full-page spread of her spring hats in the March 1959 issue of Jet. She also wrote for New York Age.

Rowena Mays, made a hat for a September 1959 fashion show that “told the audience ‘thank you’ in musical notes.” The theme of the show was “Rhapsody in Blue” and Mays wore a pale blue dress designed by Dee White. Lois Bell was her model for the day.

Suzanne Jerideau, highlighted in several fashion articles in New York Age.

“We were all ears as she told about the merits of the new cloche, the angel of a hat that has been named for the fall. This number has top billing because of friendliness of its lines. Almost any woman can wear it.

“Suzanne Jerideau, acclaimed for her original hats, says that now more than ever, women depend on hats for extra amount of enhancement to her other clothes which means that the hat designer more than ever must collaborate in spirit, if not in person, with designers of dress.”