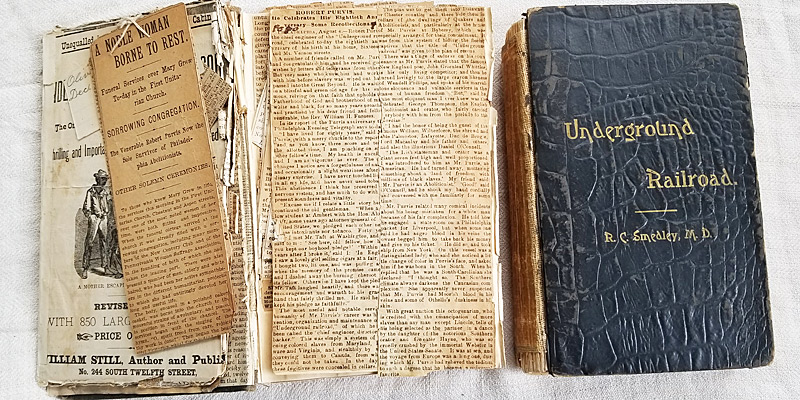

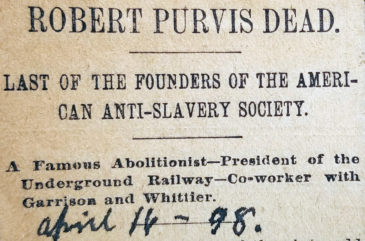

I could tell that the book had some years on it because the pages had lost their white edges and the cover was frail.

The discolored cover bore no title, just a fancy design in the center. I found the title on the spine: “Underground Railroad, R.C. Smedley, M.D.” Opening the book, I found Philadelphia newspaper clippings glued to the inside cover and stuffed in the front and back of the book, some held together with short strings.

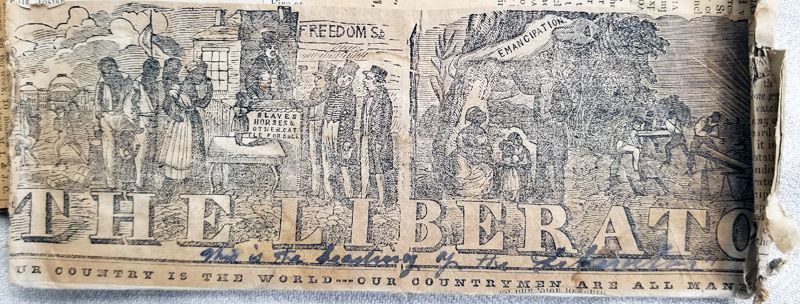

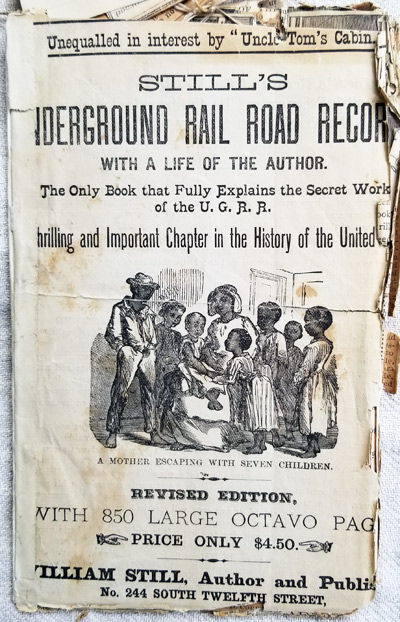

The first article was a review of Smedley’s book, but most were obituaries of male and female abolitionists. One clipping was an ad for “The Underground Rail Road Records” by African American abolitionist William Still (published in1872) and the masthead from a copy of William Lloyd Garrison’s “The Liberator” anti-slavery newspaper.

I handled the clippings carefully, because each time I opened a folded one, it split in half. The owner wrote in pencil the dates for some of the obituaries, as far back as the 1880s.

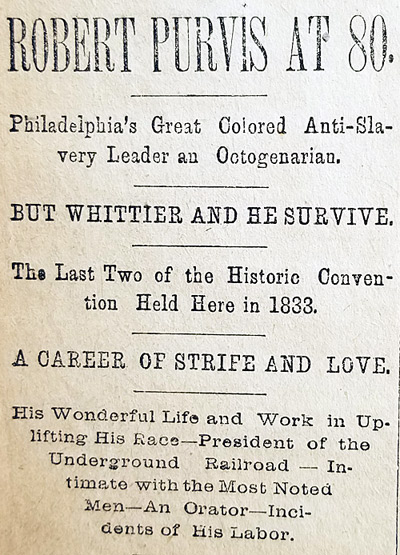

What was most fascinating were the clippings in the back of the book – practically all pertaining to Robert Purvis, another African American abolitionist who lived in Philadelphia and was doing anti-slavery work a decade before Still arrived in the 1840s. Purvis was one of the 64 male founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society (no women allowed) in 1833. He used his home in the city and his farm just outside it to hide enslaved Africans before spiriting them to Canada and other cities via the Underground Railroad.

Whoever owned this book was obviously an admirer of a man whom research showed was as committed as his contemporary William Still. But Still is the one most famously equated with the Underground Railroad.

How did I not know Purvis’ name? Googling, I found that a year ago, his current supporters were able to gain control of his house at 16th and Mt. Vernon Streets and make repairs. A state historic marker denoting its significance stands in front of it.

Smedley’s book covered the white families in Chester and contiguous counties west of Philadelphia. Each has a chapter relating the part they played in the Underground Railroad, with illustrations of each of them. Purvis was the only African American whose story was told, in the form of a letter he wrote to Smedley about his contributions. Still is mentioned four times as someone whom the white abolitionists relied on.

In the preface, Smedley wrote that the book grew out of a newspaper article he was going to write about the Underground Railroad in Chester County. But after learning of all the people who had committed themselves to this cause, he felt that their stories needed to be told.

He died before the book was published. Two days before, he had asked Purvis and Marianna Gibbons, whose grandparents were featured in the book, to edit and finish it. The book was published in 1883.

Many of the articles quote Purvis through interviews with reporters. He apparently never wrote a book about his life and work. Here’s what I culled from the articles:

Celebration of his 80th birthday, August 1890

Purvis was scheduled to have a lawn party with his friends, but all his children and grandchildren couldn’t attend so he held off until the fall. (He was married twice, first to Harriet Forten, an abolitionist and co-founder of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the mother of his children, and later a white Quaker, Tacy Townsend, a poet and abolitionist.)

“Robert Purvis, chief engineer of the ‘Underground railroad’ celebrated to-day the eightieth anniversary of his birth at his home on Sixteenth and Mt. Vernon streets,” the article began.

“A number of friends called on Mr. Purvis and congratulated him, and he received good wishes by letters and telegrams from others. But very many who knew him and worked with him before slavery was wiped out have passed into the Great Beyond. …”

(Garrison wrote in a letter: “To ordinary mortals four-score years seem long, but measuring by the events which the last eighty years have covered several lifetimes have been yours. What a panorama unfolds itself as you look backward!”)

The article continued. “In its report of the Purvis anniversary, the Philadelphia Evening Telegram says to-day:

“I have lived for eighty years,” said Mr. Purvis, with a merry chuckle to the reporter, “and, as you know, three score and ten is the allotted time, I am poaching on some other fellow’s time. My health is excellent and I am as vigorous as ever. The only changes I know are a forgetfulness of names and occasionally a slight weariness after ordinary exercise. I have never touched liquor in all my life, and I have never used tobacco. This abstinence I think has preserved my nervous system, and has much to do with my present soundness and vitality. …

“The most useful and notable service to humanity of Mr. Purvis’s career was his invention, organization and maintenance of the ‘Underground railroad,’ of which he has been called the chief engineer, director and backer. This was simply a system of rescuing colored slaves from Maryland, Delaware and Virginia and stealthily by night conveying them to Canada, from whence they could not be taken. In the daytime, these fugitives were concealed in cellars.

“The plan was to get them into Delaware or Chester counties and there hide them in cellars of dwellings of Quakers and abolitionists, particular at the house of Mr. Purvis at Byberry, which was especially arranged for their concealment. It was from this system of hiding the fleeing captives that the title ‘Underground railroad’ was given to the plan of rescue.”

Being mistaken for white

Purvis’ mother was African and his father British. He always identified himself with his African heritage.

“Mr. Purvis related many comical incidents about being mistaken for a white man because of his fair complexion,” according to the newspaper article. “He told how he engaged a stateroom on a Philadelphia packet (ship) for Liverpool, but when some one said he had negro blood in his veins the owner begged him to take back his money and give up his ticket. He did so, and took ship from New York. On this vessel was a distinguished lady, who said she noticed a little change of color in Purvis’s face, and asked him if he was born in the South. When he replied that he was a South Carolinian she declared: ‘I thought so. The Southern climate always darkens the Caucasian complexion.’ She apparently never suspected that Mr. Purvis had Moorish blood in his veins and some of Othello’s duskiness in his skin.”

His appearance was duly noted in several of the articles, including this comment: “The combination of eloquence and a striking appearance made him a figure of prominence” at the 1833 meeting that resulted in the formation of the anti-slavery society. Another writer noted that Purvis chose to live as a black man when he could easily have chosen white and avoided society’s racism.

His family’s origins

Here’s how Purvis described his family in another newspaper article:

“My grandmother was a full-blooded Moor of magnificent feature and great beauty. She had crisp hair and a stately manner. She was captured by an Arab girl one day and led to the sea where a slave ship awaited her and she was brought to Charleston. A refined woman named Day was captivated with her comeliness and bought her, educated her and treated her as a companion. A German named Baron Judah, a flour merchant, said he loved her and they were married in a Methodist church. Two children, a son and a daughter, were born. The latter was my mother. She, too, was remarkably beautiful, and my father, William Purvis, one of seven sons, three of whom had emigrated from England to Charleston, became enamored of her and they were marred.”

Purvis was born in Charleston on August 4, 1810. His father moved the family to Philadelphia to educate him and his brothers before settling in England. The father died before he could do so but left his family financially comfortable. Purvis attended Amherst College but did not graduate. Around this time, he met Garrison; Benjamin Lundy, a New Jersey abolitionist who owned several anti-slavery newspapers, and other abolitionists, including poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

His anti-slavery work

Garrison “unfolded for me his plans for publishing the ‘Liberator,’ the first number of which came out Jan. 1, 1831. In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society was formed in Philadelphia. I was a member of the convention and Vice-President of the society for many years. I was also President for several years of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and a member of its Executive Committee. I think it was about the year 1838 that the first organized society of the Underground Railroad came into existence. Of this I was made President and Jacob C. White Secretary. (Purvis also served as first vice president of the Woman’s Suffrage Society headed by Lucretia Mott.) … The funds for carrying on this enterprise were raised from our anti-slavery friends. …

“The most efficient helpers or agents we had were two market women who lived in Baltimore, one of whom was white, the other colored. By some means they obtained a number of genuine certificates of freedom or passports, which they gave to slaves who wished to escape. These passports were returned to them and used by other fugitives. The generally received opinion that ‘all negroes look alike,’ prevented too close a scrutiny by the officials.”

Unsurprisingly, Purvis didn’t have an easy time of it. Once, a group of men stood outside his house for two days waiting for him to come out so they could attack him. He and others were mobbed when Pennsylvania Hall was burned to the ground two days after it was constructed. The hall had been built by abolitionists for their meetings because they were not allowed to use other facilities.

“In those days we thought something was wrong with our work unless we encountered a mob,” he said.

Another time, he was on his way home after giving a speech when he met his English nurse on the road. She warned him not to go home or he’d be killed. He rushed home and waited on his stairs ready to kill the first person who burst through his front door. “There are moments when any man, no matter who he is, cares nothing for his life,” he said.

His death

Purvis died at home on April 15, 1898, at age 88, the last of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Several of the articles in the book announced his death.

In an earlier undated article, a reporter had asked if his anti-slavery work had paid off. “The glorious result has justified our work,” he said. “I believe in the oneness and indivisability of the human family.”

“And what of the future?” the reporter asked.

“Ah, that’s it. Let this be said: If there is one thing fixed in the mind of the colored race it is that they believe they belong here because they have been born here for decades and almost centuries; here they’ll stay, here they’ll die, and here they’ll hope for better things. … I never yet met a slave in the hundreds I helped to gain their liberty who thought he was born a slave. They all believed in their natural right to freedom.”

Glad to have found and read this past history.

I, too, was fascinated with the life of Robert Purvis & it was a joy to share his story.

I just fished reading Jim Rasenbergers wonderful biography of Samuel Colt. He briefly mentions Robert Purvis as a classmate of Cole’s at Amherst Academy.

I am so excited to read your article, having just discovered that I am a direct descendent of Robert Purvis on my maternal grandmother’s side of the family. Harriet Judah Purvis was my grandmother’s great, great, great grandmother. My family is just now learning of our connection to Robert, and I am reading everything I can about him!!

I’m excited for you. Robert and Harriet Purvis’ graves are in the Fair Hill Burial Grounds, a Quaker cemetery in Philadelphia.

Awesome find, Sherry! That book deserves to be in a museum. Thank you for sharing the photos and the excellent story about Robert Purvis — one of the most prominent leaders of the Underground Railroad.

Loraine

lorainelucas@msn.com

Here in Chester County Smedley’s book (love that you have a photo of an original

issue) is one of the significant sources on the White Abolitionists and Robert

Purvis. I was working with Kennett Underground Railroad for years and am now

focusing attention on Barnard Station Heritage Station where we plan to depict

Undergound Railroad History. Quaker Abolitionist Eusebius Barnard, my 3rd Great

Grandfather. Abraham Lincoln’s Quaker roots are to this Chester County PA Barnard

Family of abolitionists. In fact Eusebius’ brother William & 5 others from Longwood

Progressive (building still stands in front of entrance gate to Longwood Gardens,

Kennett Square PA) met with Lincoln urging him to end slavery 6 months before

Lincoln issued Emancipation Proclamation. They didn’t know they were Quaker 3rd

cousins once removed sharing original to America Richard Barnard, Lincoln’s 3rd

Great Grandfather.

If you’re in Chester County visiting, I’d be happy to give you an Underground

Railroad tour. Are you familiar with African American Artist Lee Carter (book My

Dad the Artist by LeRoy H. Carter Jr)? He local to Chester County and his artwork is

floating around.

Regards.

Hi Loraine

My grandparents lived in Chester County, not far down the road from Longwood Gardens. Their farm had been in my grandmother’s family for generations. She was a Quaker.

I had no idea that this particular area of Chester County had played such a pivotal role in the Underground Railroad during this time of Robert Purvis. Where is the best place online to research details of this time period?

Since this was a secret mission, is it impossible to determine which homes and farms (families) in this particular area hid those people that were fleeing?

Thank you for any guidance that you can provide.

Thanks for this article. For the past year, I’ve been reading lots of books on Slavery; especially Frederick Douglass’ writings.