The poster was folded in half, its aged back exposed and giving no hint of what ideas the other side held. It was lying on top of some contact sheets of black and white photos and a win for Kennedy window sign.

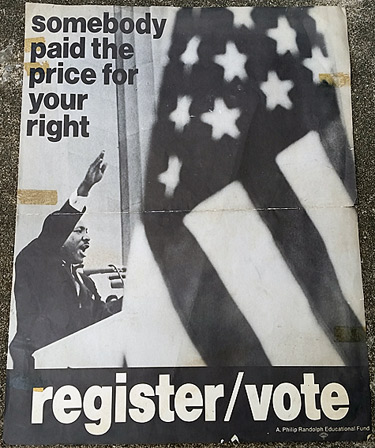

I opened up the poster and saw the black and white image of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., his right arm outstretched, a U.S. flag in the foreground intentionally blurred to put the focus on him. The wording on the poster reminded African Americans of the need and responsibility to vote.

The poster looked to be straight from the 1960s, with brown tape marks on its outer edges indicating that it had once been hung. I found another copy on the website of the Library of Congress, which dated it between 1968 and 1980.

The library also has a poster with the same message but with an image of African Americans protesting and a date range between 1965 and 1980. The earliest of these posters were done in the midst of the civil rights movement when African Americans were marching in the face of entrenched and violent opposition to both civil and voting rights.

The 15th Amendment in 1870 gave African Americans the right to vote, but it was only letters on paper. When the local laws hindering blacks were challenged over the ensuing years, southern governments merely replaced them with new barriers. For almost a century, blacks in the South endured the idiocy of literacy tests, grandfather clauses, poll taxes and violence that kept them from the voting boxes.

Tired of being denied common but significant rights, they marched on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, and crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge headed from Selma to Montgomery, AL, in 1965. That “Bloody Sunday” attack by state troopers led to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act that year.

The act changed the face of the voting population. Registrars had signed up 250,000 African American voters by the end of 1965. Voter turnout jumped from 6 percent in Mississippi in 1964 to 59 percent in 1969. Before the law was passed, only 5 percent of African Americans were registered in that state.

Provisions of the law forbade local governments from making any voting changes or redistricting without approval from the Justice Department or a federal court in Washington. These provisions not only affected nine southern states, but towns in California, New York, Florida and four other states.

One of the leaders pivotal to the movement for freedom and voting rights was A. Philip Randolph, first president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. He was the organizer of the 1925 union that fought for better working conditions for black porters and maids on Pullman Company trains. Randolph was also the main architect of the March on Washington that drew more than 200,000 people.

The poster was produced by the A. Philip Randolph Educational Fund, which was part of the A. Philip Randolph Institute founded by Randolph and Bayard Rustin in 1965. The fund organizes education programs between African Americans and labor groups. Among its earliest projects was a joint union apprenticeship program to train and place black workers in building-construction trades.

The message on the poster at auction is just as relevant today, if not more. Over the last decade, provisions of the Voting Rights Act have been challenged in court by some of the same states that had stemmed black voting in the past. The act is outdated, they say, pointing to the country’s election of its first black president.

In 2009, the Supreme Court upheld a provision in the 1965 law that required several states to get approval before making any changes in their election laws. In 2013, the court struck down the formula used to determine which states were subject to the provision, effectively killing it.

Another obstacle are Voter ID laws, which are in play in more than 30 states, according to the ACLU. These have the same foul odor of those long-ago poll taxes and literacy tests.