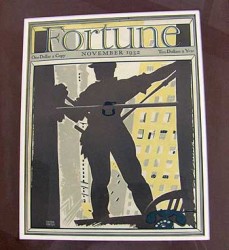

On first glance, the image reminded me of a mural I’d perhaps seen of workers building a skyscraper in Chicago. I don’t remember where I saw the work – I’m sure it was during a trip some years ago to the city – but this one had that same early 20th century feel to it.

The worker was plastered against skyscrapers in the background of a framed illustration hanging on a wall at the auction house. I was so focused on the buildings that I didn’t instantly realize what the man was doing. He was on the cover of the November 1932 issue of Fortune magazine, him drawn in a cool chocolate brown tempered by a background of soft cream and yellow accents. Then I realized that he was up high, washing windows on another of those monoliths.

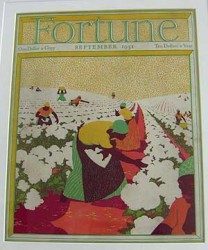

The image also stirred my memory of another Fortune magazine cover that I bought at a Black memorabilia show some time ago. It was a September 1931 issue that depicted a group of African American women picking cotton in some field, likely in the South.

Both of the covers were nicely executed, resembling more art that illustration, and that’s why I was smitten with them. When I first saw the worker cover, I headed right for it because I recognized the look. I was immediately curious about both it and the artist, a man named Ervine Metzl.

Metzl was one of the many artists who illustrated covers for Fortune, founded in 1930 by Henry Luce and his partner Briton Hadden. The two men had already started Time magazine, which was a big hit, and Luce gambled that the Depression was a good time to start a magazine about business – even when many businesses were failing and the country was in a funk.

His Fortune was instantly popular, mainly because of its covers. It was like no other business magazine of its time, straying from the use of stats and seemingly boring content. It had the aura of an upscale publication with an aim of humanizing business and the men behind it. The magazine went farther than that, though, imparting a social message from outside the corporate offices to the “farms and factories” that fueled those businesses.

Luce hired some of the best writers – including John Kenneth Galbraith and Archibald MacLeish – and commissioned some of the best illustrators to design covers and illustrate stories. Mexican artist Diego Rivera created several covers – including one with a Soviet hammer and sickle – as well as Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias. Illustrator Antonio Petruccelli designed more than 25 covers in the 1930s and 1940s.

Take a look at this interesting Petruccelli illustration of an overhead view of a meeting around a conference table. On first look, it’s only a meeting, but if you squint, as noted in a book on graphics, it looks like a gear for a machine.

“Fortune artists illustrated the growth of 20th century industrialization with streamlined, modern graphic styles and layouts, as well as more rustic, traditional subjects with more conventional illustration styles,” according to a Smithsonian article.

During the 1930s, Fortune’s covers showed the intersection of the industrial and agricultural worlds, as one was overtaking the other. My two covers exemplified those contrary cultures: the agrarian, as seen in the African American female cotton pickers by Edwin A. Georgi (mine is not signed) and Metzl’s urban window washer (done at a time when Luce treated the skyscraper as if it were an eighth wonder of the world to be celebrated).

Even more dramatic were covers juxtaposing the past alongside the future, as in these 1930s covers.

Metzl got his arts education at the school of the Art Institute of Chicago. During the 1920s, he created posters for the Chicago Transit Authority as part of its campaign to attract riders. He also designed stamps for the U.S. Post Office, illustrated books and wrote one of his own about posters.

Georgi taught himself to draw while he was recovering from an injury during World War II. After the war, he created ads, covers and story illustrations for a range of magazines. He was more of a pin-up-girl artist “without actually being pinpup,” according to one article.

The women cotton pickers on the Fortune cover were afar afield of his pin-ups, so I would love to know how he ended up with that assignment.