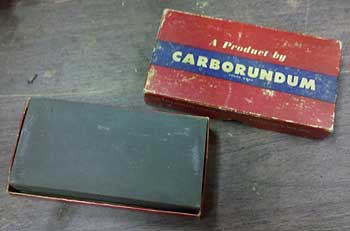

As soon as I saw the word on the label, I recognized the material. It wasn’t something that most people would notice unless they still used a strop or hone to sharpen a man’s razor.

“Carborundum” was printed in large block letters on the cover of the box, which was about the size of a large Hershey chocolate candy bar. The carborundum – the color of wet concete and just as solid and hard – was still in its original box, unused.

The word forced a name to collect inside my head: African American artist Dox Thrash, who with two colleagues at the Federal Arts Project in the 1930s came up with a way to use the substance to develop a new medium for their artwork.

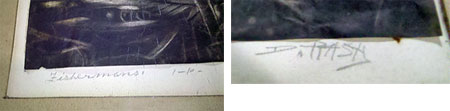

Thrash, though, is the artist most remembered for his part in discovering this technique – called carborundum mezzotint, carbograph or Opheliagraph (after his mother who had recently died) – and using it to its fullest in most of his works, including a recent piece I came across at auction.

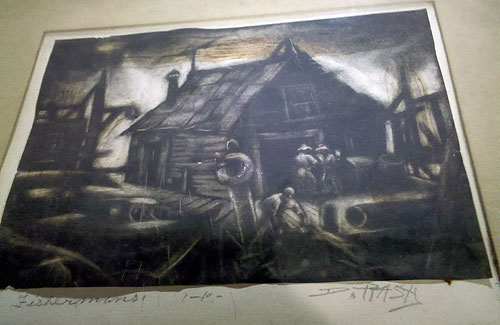

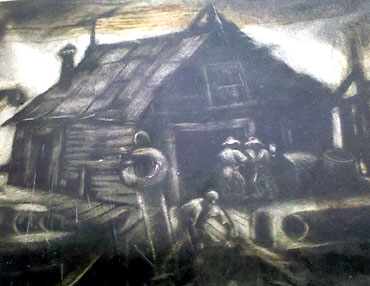

The artist had penciled the title “Fishermens” in the left corner, numbered it 1/10 with no date and signed it. The print was dark in tone with some light shadings – the characteristics of the carborundum technique – but it also looked as if it could use a good cleaning. Through the darkness, I could see the images of fishermen on a wooden dock and an old shack in the background.

When the print came up for auction, I knew that at least one other buyer was also interested. He always bids on African-American- related artwork and memorabilia for sale to his New York buyers, and he had deep pockets.

I was looking to buy the print for myself and I stuck with him in the bidding until I had to bow out, because the price was getting too high for me and he obviously wasn’t going to stop. So, I’ll have to wait for the next Thrash carborundum print to show up.

Thrash was a renowned artist in the late 1930s – when the carborundum process was developed – until the 1950s, but he soon faded into obscurity (he died in 1965).

Thrash was born in Griffin, GA, in 1893 to Gus and Ophelia Thrash. At age 15 he joined the flow of black people escaping the South during the Great Migration to northern cities that promised more but delivered the same or less. Thrash ended up in Chicago, where he took night classes at the Art Institute before enlisting in the Army in the unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

He returned to Chicago after the war, but by 1925 had found his way to Philadelphia, where he first made prints as a student of artist Earl Horter.

Thrash joined the Philadelphia Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Arts Project around 1934 or 1935 and became one of its most well-known participants. Carborundum was not a new substance; it was a hard abrasive material that had been developed in the 1890s and was used for grinding and polishing (and on razor strops and hones). Thrash and other artists used it to clean lithographic stones.

Around 1937, Thrash, along with WPA artists Hugh Mesibov and Michael Gallagher, determined that they could use carborundum (or silicon carbide) crystals to roughen a copper etching plate so it would trap ink to create varying tones of light and dark. Here is Thrash demonstrating the technique.

The discovery made him a very sought-after artist, nailing him a solo exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1942. The museum would hold another solo exhibit titled “Dox Thrash: An African American Printmaker Rediscovered” in October 2001-February 2002. Thrash participated in group exhibitions at the Pyramid Club in Philadelphia in 1946 and the New York World’s Fair in 1940.

A social realist, Thrash’s subjects were the black people and surroundings that he knew – the fishermen in the auction print, workers at a war plant, everyday people like the man in “My Neighbor” or “Mary Lou,” female nudes, the south where he grew up, and the Philadelphia streets and communities that became his home.

Even with his notoriety, Thrash had an endless array of jobs, just like many African American artists during that time, to keep afloat: elevator operator, vaudeville performer, railroad porter, dancer, graphics designer and steamship steward. In the 1940s, he painted a WPA nursery rhyme mural for the children’s ward of Mercy Hospital, an African American hospital that is now closed, and he was a house painter for the Philadelphia Housing Authority, retiring in 1958.

The WPA gave 70 of his prints to the Free Library of Philadelphia in 1943, which mounted an exhibition in 1987.

Thrash’s repertoire included more than just carborundum prints. He also created paintings, lithographs and etchings. I purchased a painting from a gallery a few years ago titled “Suburbia.” It shows a woman in a rural area looking out over an expanse of houses in the distance, possibly with worry about how suburban sprawl was encroaching on her life.

According to the gallery, the circa 1940 watercolor and ink painting was a study for a print at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.