They were in a different CBS studio each Sunday, this group of singers with some of the best voices in spiritual music. But Wings Over Jordan couldn’t just walk through the front door of hotels to the floor where the studio was waiting.

This was the mid-1940s in the South’s most inhospitable towns, so they had to take freight elevators to the local studios – some with only a microphone and not much more.

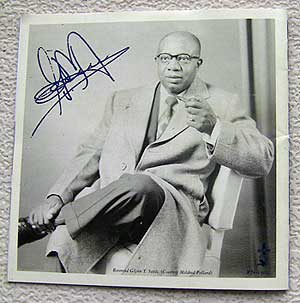

Kenneth Slaughter had arrived to this group of a capella singers late. The Rev. Glynn T. Settle and his Cleveland-based choir were winding down in much the same way as the war in Europe. He had kept it going for more than a decade, starting out with 35 singers on one radio station in his hometown and now down to about 20 joining Slaughter at CBS affiliate studios.

“We sang at every CBS station in the United States every Sunday morning,” Slaughter recalled.

I had never heard of the Wings Over Jordan until a local minister mentioned the choir at an event I was attending a few weeks ago. Slaughter is one of the last living members of the choir, the minister had said. I didn’t know if that was true – it’s hard to verify the first and last of anything – but I was curious about this famous group that had slipped past me. One blogger noted that it was the first black radio choir with a national audience.

I’m always discovering aspects of black history (and as such, American history) that have gotten lost in the lack of telling or died away because no one’s around who remembers. In the last month, I’ve come across one other bit of African American history that hit the airwaves when radio was just starting to get its wings.

It was a show called Destination Freedom, a regional broadcast from Chicago that was created in 1948 by Richard Durham. He researched and wrote dramatic scripts based on the lives of famous African Americans.

Now, I was back in early radio with a spiritual show that was immensely popular.

“When I was a kid, I used to hear them on Sunday morning,” said Slaughter, 90. “I never dreamed I’d ever be singing with them. … I wanted to play the saxophone in Count Basie’s Orchestra.”

“When I was a kid, I used to hear them on Sunday morning,” said Slaughter, 90. “I never dreamed I’d ever be singing with them. … I wanted to play the saxophone in Count Basie’s Orchestra.”

He grew up in a household with five other siblings, a father who worked at the Post Office and a schoolteacher mother in Columbus, OH. His grandfather Jonas had escaped slavery to save his life after trying to teach other slaves to read. In the late 19th century, the 14-year-old apprentice Jonas Slaughter had also cut the hair of Samuel Clemens, but it would be 50 years later before he knew that “Mr. Clemens” was the writer Mark Twain, according to an Urbana, OH, newspaper account.

Kenneth Slaughter attended Wilberforce University for two years in the 1940s, traveling and singing spirituals with a group called the Wilberforce Singers, he said. He had planned to major in music but realized that he had a better shot at finding a job if he chose accounting. At age 22, he was working in a store selling clothes when a member of the Wings of Jordan came in to buy outfits for the next tour.

“We need a tenor,” the man told him. “I had been thinking about going up and trying out,” Slaughter said. “This like fell in my lap.”

He auditioned in Columbus and then headed up to Cleveland, where Rev. Settle had first formed his Wings Over Jordan back in the 1930s.

Back then, Rev. Settle had watched as other ethnic neighborhoods got their own radio program, so he and his Gethsemane Baptist Church choir went down to WGAR to ask for a show of their own. They not only got a show – “The Negro Hour” began airing in 1937 (or 1935, depending on what you read) – but also a choral director and vice president. The white station manager, Worth Cramer, saw this as a good way for him to get into arranging black music and so he set about re-shaping the choir, according to a Time magazine article.

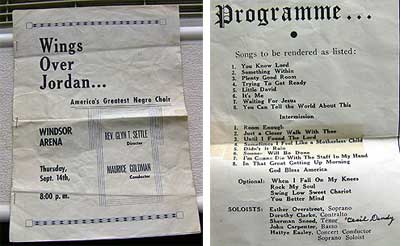

CBS picked it up the next year – and the choir changed its name to the words of a song that Rev. Settle’s mother was said to have sung – and it went national. By 1940, the show was on 100 stations in this country and by shortwave around the world, according to an NPR article quoting a Time magazine story. A St. Petersburg (Fla.) Times story stated that 10 million people heard it.

The radio show included such speakers as scholar W.E.B. DuBois, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., among others.

“Mr. Settle spoke but didn’t sing. Before every song, he described it,” Slaughter recalled. “He had a deep melodious voice. White people loved his voice. His mother and father told him if black and white people could get together they could get along. That was his thing.”

Over the years, the choir had sung in 45 states and five foreign countries, Slaughter said, performing both on the radio and in concerts. It was said to be the only choral group sent overseas during World War II.

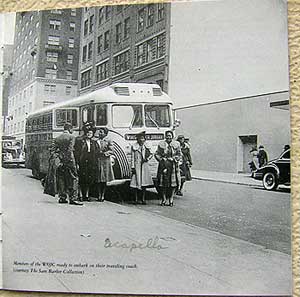

The singers rode a Greyhound-like bus with a large handwritten “Wings Over Jordan” sign across the middle, and across the top “CBS Network Artists.” Slaughter and the others surmised that the top-most sign was placed there to guard them against attacks in Southern towns.

Slaughter sang first tenor and was called on to sing solo only once. “I was very nervous,” he said. “I didn’t feel like I had soul. I didn’t. Soloist Esther Overstreet used to sing and she’d have tears streaming over her face. I asked her how could she sing those slave songs. She said, ‘I’m not thinking about slaves. I’m thinking about the terrible things, personal things, trauma in my own life.’ Women had a hard time back in those days.”

Life on the road, especially in the South, appeared to be both entertaining, daring and dangerous.

They looked for places with black and orange signs that said “Colored” where they could get food at the back. At one stop, they were told to make their own food, and the female singers “went in the kitchen and fixed the sandwiches themselves,” he said.

At a stop in Shreveport, LA, with no place to stay, they ended up in a whorehouse while the prostitutes were sent out to sleep in a sugar cane field. Fearful of bed bugs, no one took their luggage into rooms with cracks in the ceiling and galvanized steel in the shower.

In Harlem once, they stayed in a hotel that was home to dope pushers and pimps. Sometimes, they stayed at the Woodside Hotel, which was immortalized in Count Basie’s 1938 tune “Jumpin’ at the Woodside.” “It had a restaurant in the basement where all the great bands practiced,” Slaughter said.

Another time, they were in Florida, hadn’t eaten in 14 hours and finally found a place at the bottom of a hill near a river. They were warned by a white man that a mob of white men with bats was forming to attack them and wreck their bus.

“They weren’t used to seeing black people in shirts and dresses during the week,” he said. “You were supposed to have overalls on. You were supposed to be working.”

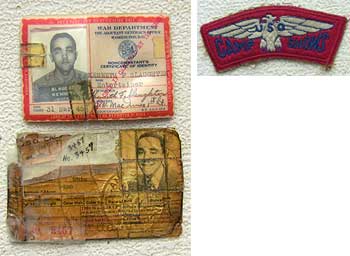

Then in 1945, Slaughter took his first trip by military ship to Europe as part of a USO morale-booster. The members waited in Harlem for six weeks while Saks Fifth Avenue made military uniforms for them to wear all the time on their European trip. They were also given the rank of captain that afforded them special privileges if they were detained by the enemy, he said.

Their military outfit consisted of a patch with the emblem “USO Camp Shows,” and they carried a badge identifying them as non-combat. Written in red across the badge were some ominous words: “Valid Only If Captured By The Enemy. 31 Mar 45.”

Morale was suffering among black troops in a military that took them as soldiers but didn’t accept them, their jobs confined to the menial duties most had left back home. The Wings Over Jordan was sent to boost their spirits with music that spoke of aiming high when the soul was low.

The singers rode Army buses to Genoa, Florence, Rome and other Italian cities, stopping at every camp. Slaughter met up with his brother Carl who was stationed there with the Army’s 365th Infantry Regiment, part of the 92nd Infantry Division that adopted the name Buffalo Soldiers given to black soldiers in the 1880s by Native Americans.

They were even called on to sing at special events, said Slaughter. In 1945, they sang the Lord’s Prayer at a special program marking the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and “God Save America” when the Italians returned Christopher Columbus’ ashes to Genoa after hiding them for safekeeping during the war.

“We didn’t (travel) like Bob Hope with the pretty girls,” Slaughter said. “We were (called) a foxhole unit, because we had to try to talk to ordinary soldiers who were fighting. We had to go to the hospitals where they were injured.”

The tour was booked for six months but was extended to 10 months. Slaughter didn’t make all of it, though. He got sick and was hospitalized for three weeks, losing 15 pounds. He and three others returned to the States in late 1945 and his stint with Wings Over Jordan was over.

The choir stopped broadcasting on the radio in 1947. Rev. Settle kept it going for a while, and in 1948 was faced with a walkout by some of its members who complained of being underpaid.

Meanwhile, Slaughter studied accounting, got married and moved to Philadelphia to work with the state auditor’s office. He got a letter in 1947 announcing that he was being given a service award from the USO for his work overseas.

My Father is Sherman Sneed a member of the 1945 Wings Over Jordan. He is the fourth man on the right side of the program photo.

I have audio tapes recorded in 1992 where my dad recalls his time with Wings Over Jordan…from being on the road across the country in that infamous bus. Talks about after Rev. Settle got ill, my dad was also the bus driver and did the narration. Includes the challenge of where they stayed when on the road, as well as having to get food in the back of restaurants. Vivid accounts of being in NY getting their uniforms and shots before going to Italy. My dad was a newlywed just two weeks before the USO tour, promised my mother he would only be gone for 6 months. So he was one of the three with Mr. Slaughter who returned back to the States. So much rich history. Wonderful to have his story mirrored in the article. Thank you!

I’m currently working on a mini documentary to keep the history alive!

Signed by a Daughter of Barritone Soloist Sherman Sneed.

Hello,

Thank you so much for making so much history available. My Goddaughter’s grandfather is one of the men on the Amen CD. The photo standing in the “V for Victory” formation in the early 1940s WRHS image – if you start at the front of the V, he is the fourth person back on the left. 2 women, then one man, then him His name was Charles Ross Jones Jr. I wondered if you had any additional photos or history that would help them know him better.

It’s an unusual request, and I am grateful for your reading it no matter if anything is available or not, Thank you

John Pratt Booker

Hi John, unfortunately, I do not have any more information. Sherry

I really enjoyed the information about Mr Slaughter and the Wings Over Jordan choir!

Thank you so much,

Robert Hill

Thank you. I grew up listening to the music on the radio and recordings. My dad sang along doing all the bass parts and I loved to hear him sing.