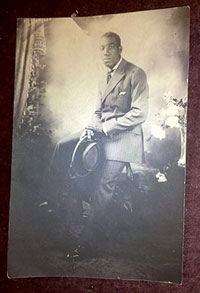

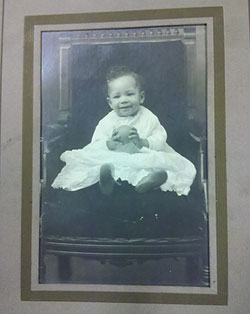

Were my eyes deceiving me, I wondered as I glanced at the group of photos lying in the bottom half of a small flat box on the auction table. A nicely dressed and coiffed black woman sitting in a chair. A clean and tidy black toddler standing with a cane. A black baby boy in white smiling into a camera.

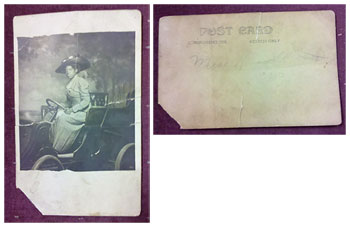

And in another half-box: A black woman in a wide hat posing behind the wheel of a 1920s car.

These were not the types of photos I normally see of black people at auction. What I see much too often are us in the stereotypical roles that only an evil mind could create. Rarely are we shown as normal human beings.

These photos showed a family that crushed the stereotypes. They were apparently done in a photography studio and paid for by them, and then tucked inside those old beautiful paper frames bearing the names of the studios. In this case, they were the Belt Studio in West Chester, PA, and Jackson on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn, NY.

The photos reminded me of the work of photographer James Van Der Zee, who was well-known for shooting pictures of people living in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s.

The lot at auction contained about 18 to 20 photos – along with some bills for services – and they sparked the interest of several auction-goers besides me. I knew that I would not get them cheaply, because several regulars were on hand who readily snap up black memorabilia. Since these photos were so extraordinary, I knew that I would have to aim high to stay in the bidding.

From the bills, I surmised that the family moved from Brooklyn to West Chester in the late 1920s (one bill dated March 1928 was from a moving company). There were others for work done on a house in West Chester. Some were made out separately to Rhoda Wilson, William Wilson and Clementine Wilson.

Here are some other interesting items I found in the stash:

A real photo postcard of Rhoda Wilson posing in an early automobile, with her name written lightly in pencil on the back of the postally unused card. These types of postcards were pretty popular during the early 20th century.

A photo of a woman who had stopped in mid-ironing to pose for a photo (taken with a Kodak camera?) inside what looked like her home. It made me realize how uncommon it was to see a domestic photo of a black woman ironing her own clothes.

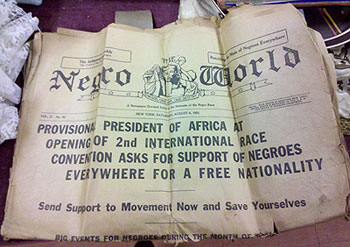

A copy of Marcus Garvey’s newspaper “The Negro World” from Aug. 6, 1921. It was yellowed and folded, but was still readable.

Was this a very political family whose beliefs matched those of Garvey’s? I’d love to know. The Negro World, a weekly newspaper started by Garvey in 1918, unabashedly espoused his philosophy of black nationalism and self-help among blacks. Garvey had founded the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1914 in an attempt to unite black people throughout the world around the notion of self-independence. He wanted Europeans out of Africa so the continent could be a haven where blacks could build their own government.

As part of UNIA, Garvey started the Black Star Line in 1919 as a commercial shipping company as well as a way to transport blacks to Africa. It was beset by problems from within and without, finally shutting down three years later.

I could imagine the adults in the photos empathizing with what Garvey was preaching. Their photos showed generations of a proud family who had made its own way: From grandmother Rhoda to granddaughter Ruth and grandson Clarence.

And here I was at this auction house hoping to take them home. Once the auctioneer got to the table, he almost missed the photos because someone had turned them face-down. Desperate bidders will sometimes resort to hiding or moving items (or here, obstructing them) to squelch the competition. In this case, however, the auctioneer was keen enough to figure it out.

He got the bidding started, and it progressed past $40, then $50, then $60. It was clear to me that the other bidder would not let up. So, when the auctioneer threw out $100 and looked at me, I slowly turned and walked away. “You can give it to her,” I said jokingly. “She’ll have to pay for it, though,” he answered to chuckles from all of us.

She got the lot for $90. I approached her afterward, remarking on how great the photos were. A dealer, she said that she had customers who’d be interested in them. As I shuffled through them to show her the one that I found especially adorable, she handed it to me – as a gift. How sweet of her.

It was the baby boy in white, below.

Fascinating post! I was googling “vintage black women” when I came across this entry – I don’t go to auctions, myself, but I have long been intrigued by vintage images of African-Americans in non-stereotypical depictions.

It started when I began sharing vintage photographs of my own African-American family on my Flickr site, and I quickly became interested in seeing vintage & retro imagery of OTHER African-American families and individuals.

I love the types of photography exhibited above because it shatters stereotypes and depicts the reality of the Black community, our history, and our accomplishments.

Thanks, Tori. I come across these beautiful photos from time to time. Like you, I’m always happy to find ones that we take of ourselves because they are never stereotypical.

Sherry

Clementine and William are my great great grandparents and Rhoda is my great great aunt their daughter

Fantastic, Hope. I’d love to know more about them.