A young Isaac Scott Hathaway had slipped away from his father and sisters at the Cleveland museum. He went looking for a specific sculpture that he was certain would be there.

Finally, the Rev. R.E. Hathaway found his son and asked why he had wandered off.

“I told my father that I was trying to find a bust of Frederick Douglass here,” the son told an interviewer for the government’s Federal Writers’ Project in 1939. “Teacher says the truly great people are perpetuated in marble and bronze. And Douglass was truly great.

“My dad replied, ‘Yes, son, I know, but we shall have to produce artists of our own race to portray our own great men. … Well I made up my mind that day that I was going to make busts and statues of our great Negroes and put them where people can see them.”

The year was 1881 in the midst of the Reconstruction era, more than 25 years after slavery. The young Hathaway was nine years old.

He would fulfill his promise over the next 80 years as a ceramics artist and teacher at colleges in the South. He told that interviewer in 1939 that his American heroes were already “scattered in schools and colleges throughout the United States and some in South America, the West Indies and Canada.”

In 1907, Hathaway crafted 12″ busts of Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Paul Lawrence Dunbar and George Washington Carver. They were made of plaster and painted to give them a bronze look. He began selling them for $1 each, and by 1918, he was advertising them in the NAACP’S Crisis magazine for $1.50 each or 4 for $5.

Hathaway produced more than 100 busts and life and death masks of famous black people. His medium was plaster and bronze.

I had come across Hathaway’s name last year at an auction house that was selling coins. The auction included two that he had designed: commemorative half-dollar coins of Washington in 1946 and a double-silhouetted combined coin of Washington and Carver in 1951 for the U.S. Mint.

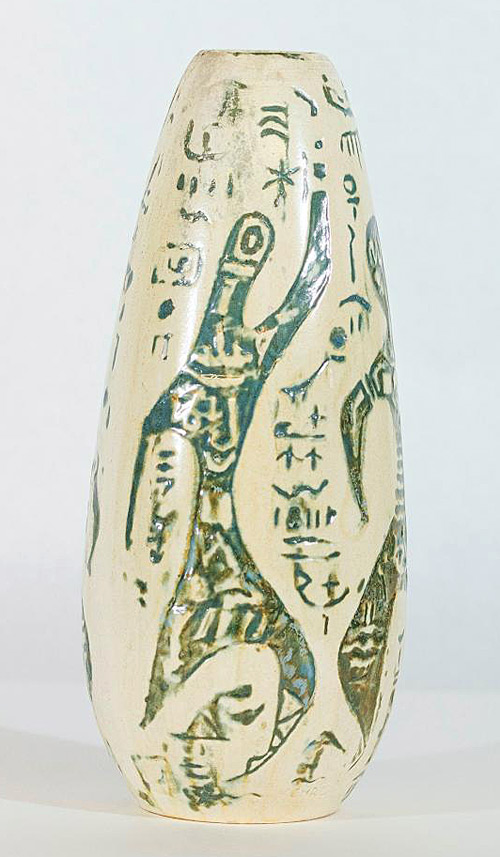

I was reminded of him recently when a friend noticed a vase for sale in an online auction on July 11 by blackartauction.com. The vase was not made by Hathaway, but it was fired at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama, where he had headed the ceramics department for 10 years. The cylindrical vase was cream-colored with green dancing figures and symbols.

Finding Hathaway piqued my interest about other African American ceramics artists. He was one of several during the 1940s and 1950s. They included Henry Letcher; Wilmer James; Joseph Gilliard, who in 1935 set up the ceramics program at Hampton University and taught there for nearly 50 years; William Artis, whose works show up at auction pretty often; Tony Hill and Doyle Lane. The most well-known was Sargent Claude Johnson, whom I was more familiar with as a sculptor and painter.

Even before them were the enslaved and free Africans whose names we may never know, except for Dave the Potter. Dave Drake was an enslaved African in South Carolina who made huge beautiful pottery inscribed with poetic verses.

One of the foremost contemporary African American ceramics artists is David MacDonald, born around the time when Hathaway and the others were working. He studied under Gilliard at Hampton and Robert Stull in the graduate program at the University of Michigan.

In 2017, Chicago State University held an exhibit of contemporary African American artists who worked in clay. They included Aaron Downs, Juarez Hawkins, Malika Jackson, Christine LaRue and Roberto Lugo – born of Puerto Rican parents but whose subjects are African Americans.

The vase in the online auction was inscribed “Tuskegee Institute Pottery” on the bottom and the name “Henre” on the side, according to the auction-house description. Googling, I found several versions of this vase, as well as other vases inscribed “Made by Student, Tuskegee Institute Pottery” from the 1950s.

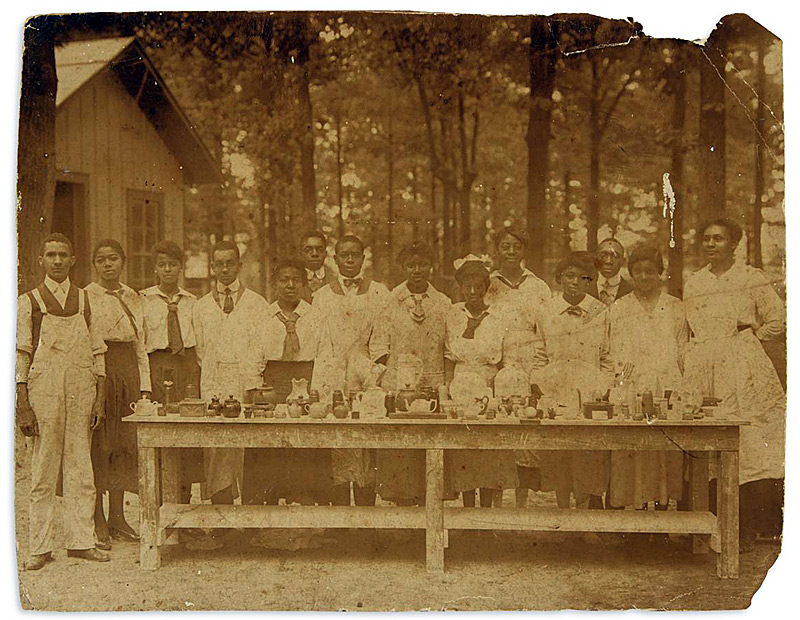

The online auction house noted that Hathaway had established the ceramics department at Tuskegee in 1937. Some sites identified him as a founding member. The department’s mission paralleled the focus of the school – and Washington, who started it in 1881- to teach mechanical skills aimed at preparing students to make a living. Washington died in 1915.

The school apparently sold pottery made by students as a way to earn money for themselves and the school itself. It’s similar to what Berea College began doing in the 1920s – selling student-made brooms. That college in Lexington, KY, was founded in 1855 by an abolitionist as the only racially integrated and coeducational school in the South.

Hathaway was born in Lexington in 1872 into a family that encouraged his artistic interests. After high school, he illustrated textbooks and drew racehorses to raise money to pay college costs for himself and his sisters. He studied art, sculpture and ceramics at several schools, including the New England Conservatory of Music, Cincinnati Art Academy, State University of Kansas at Pittsburg and the State University of New York at Alfred. While in Boston, he created his first bust: Bishop Richard Allen, one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1915, Hathaway taught ceramics at Branch Normal College, a black school that is now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, where he stayed until he was hired at Tuskegee in 1937.

Even before Hathaway arrived, Carver was experimenting with Alabama’s red and kaolin (white) clay. He had been hired by Washington back in 1896 as head of the agricultural department and was known for his scientific curiosity.

Carver kept some pottery on shelves in his office at Tuskegee. He acknowledged to a visitor in 1943 that they were crude but he had a purpose for making them: to show the manufacturing possibilities of southern clay. He had pulled pigments from red and kaolin clays to create wood stains, face powder, dyes and paints.

Hathaway was said to have been the first to make Alabama’s stubborn kaolin clay suitable as a medium for artwork. He used his own formula to tame it. He seems to have spent his time making his plaster busts.

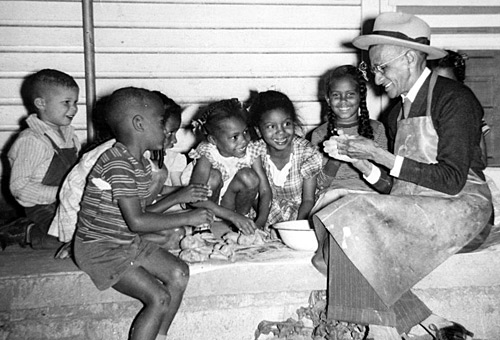

In the summer of 1947, he taught a ceramics class at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University). It was the school’s first such course, and he was the first African American to teach at the white segregated school. He left Tuskegee that year and became the director of ceramics at Alabama State University, an African American college. He stayed there until he retired in 1963 and eventually moved back to Tuskegee, AL. He died in 1967.

There’s no question that Hathaway was a master of clay. In the 1939 interview for the Federal Writers’ Project, he told of how he created a plaster cast of the ground and tree where a man had committed suicide in Louisville, KY, in 1903.

“The work was finished and set up in the courtroom as an exhibit in the evidence. So realistic was the ground and the tree here represented that the opposing council, Attorney O’Neal, accused the defense with mutilation of private property, his view being that I had literally undercut the ground and tree and brought the natural scene into court.

“When I was called to the stand, (defense) Attorney Bullit asked, “‘Hathaway, what is that?’ pointing at the cast.”

“‘It is a plaster cast,'” I replied. “‘Can you prove it,'” asked Attorney Bullit.

“‘Yes, sir,’ I said, taking a knife from my pocket, sticking it in the tree and revealing a white spot of plaster. This aroused quite a commotion in the courtroom as there were many others beside Attorney O’Neal who thought the cast was an actual figure.”