I liked the sound of Leroy Johnson’s voice before I got to meet him. It was strong, happy, eager to make my acquaintance, as people of his generation might say.

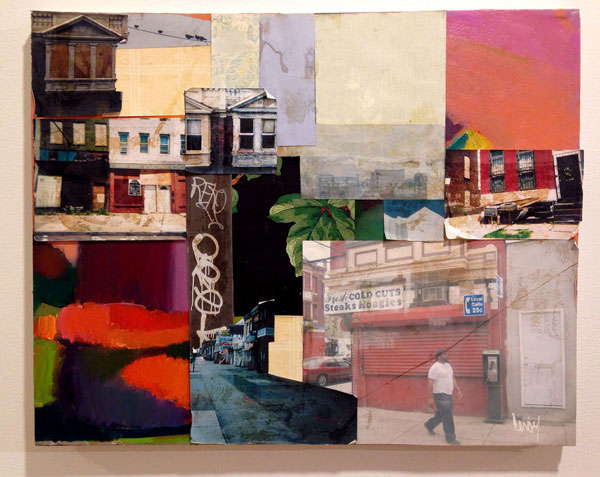

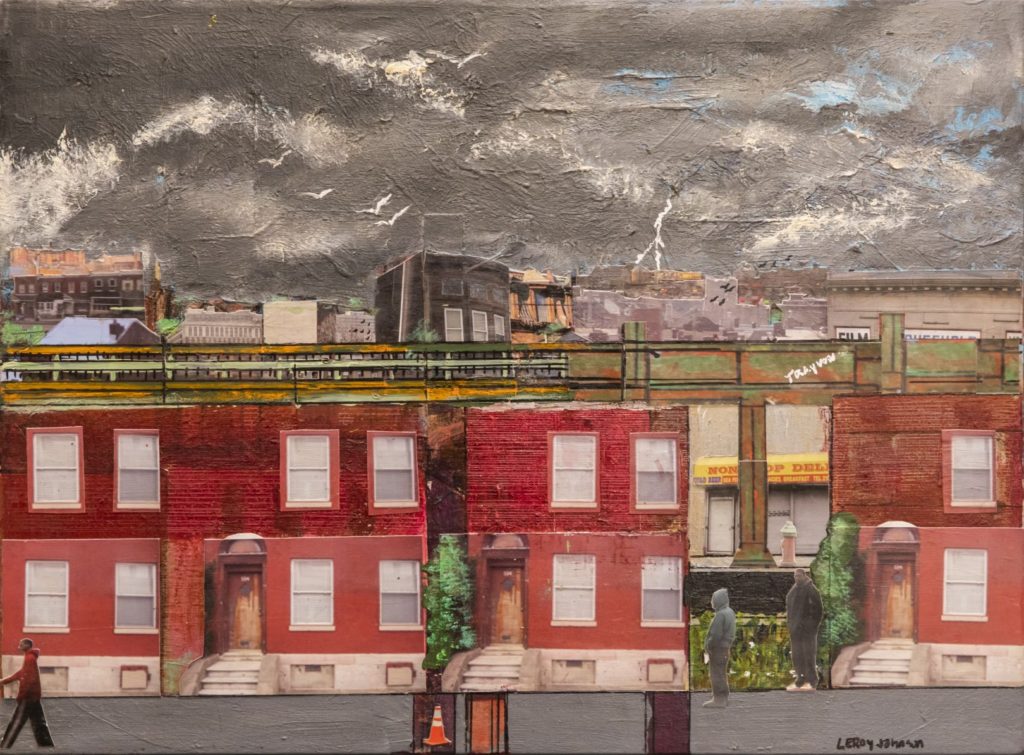

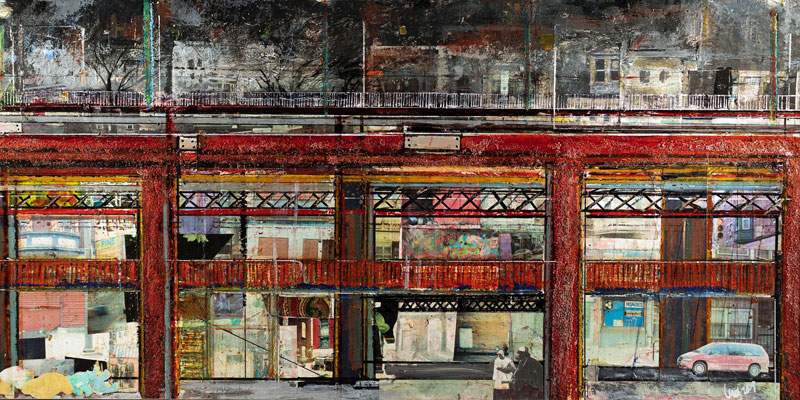

I had only learned of this African American artist about a week before. A friend told me that a painting by him was sold at the Black Art Auction in early June. I had never heard of Johnson but loved the gritty vibrancy I saw and felt in the mixed media painting titled “The El Series.” His image of this iconic elevated train in Philadelphia reminded me of another of its city-centric native sons, artist Ed Jones.

I just had to meet Johnson. He was like so many artists I had written about – deep into their work, and unrecognized and little-acknowledged by the larger outside art world.

The morning I called Johnson, he was at Jefferson University Hospital and seemed delighted that I wanted to write about him. He was as ebullient as I’d seen and heard him online in audio and video interviews. We made plans through his friend Genevieve Carminati to meet after he had arranged his treatments. I didn’t pry because you don’t ask folks about their health.

We never met, however. I learned in mid-July that Leroy M. Johnson had died of lung cancer two weeks before, on July 8, 2022, at age 85. I was crushed. Although I never fully knew him, I felt a warm connection to this man who found beauty in the articles we discard unceremoniously.

I decided to tell Johnson’s story the way I told of others whose works I picked up at auction and whose self was no longer with us – through research about who they were and what inspired them. I have not yet come across one of Johnson’s gems at auction.

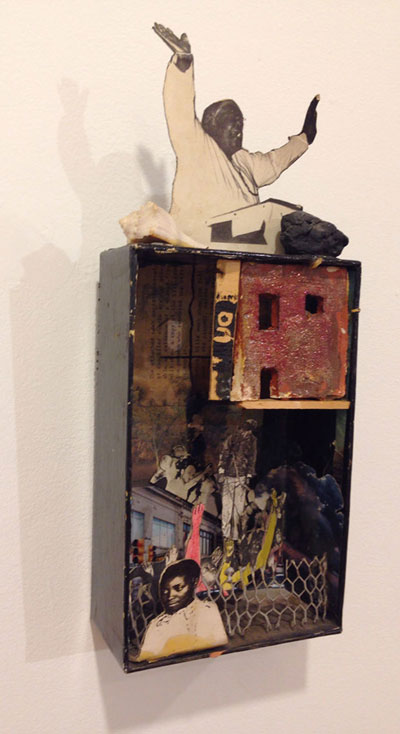

Johnson was largely a self-taught artist who found his voice in the layered nuances of the city that mused him. He was a collagist who used the stuff we scrapped – “they talk to me,” he told a reporter once – to create artworks from single bold paintings to three-dimensional houses that looked both fragile and sturdy. He worked in mixed media, charcoal, acrylic and clay. At one point, he made pipes from clay he found in digs across Philadelphia. He also produced prints.

Johnson considered himself an outsider, an original art-maker who followed his own path and eschewed the “sterilization” that he perceived as a fundamental problem with formal art education (he never went to art school for a degree). He painted what he wanted with materials and images within his eyeshot: cardboard, metal, fabric pieces, posters, cutout photos of people and old buildings in need of fix-up, corn husks, caution tapes, street and shop signs.

“My art bears witness,” he said in an artist statement. “I attempt to express not only aesthetic issues, but social, moral and spiritual as well. My influences are many: clay, naïve art, collage, combining painting, jazz and the spirits with(in) them. My work is concerned with life and existence in the inner city.”

His growing-up years

Johnson was born in 1937 in Eastwick, a diverse neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia near the then-nascent Philadelphia municipal airport. When he was about 7 or 8 years old, he read Richard Wright’s “Native Son” and asked his mother who wrote it. “A colored man,” she replied.

“At the same time, I heard a voice say, ‘You’re going to be an artist.’ So that was my first inspiration,” he told a producer for “The Inside Look” series in 2019. “Being a child and being brought up a Christian, you can’t argue with God,” he told another interviewer. “So I accepted that.”

Drawing and reading were always his twin passions. “I copied everybody when I was little, especially in pen and ink and pencil because that’s what I had available,” he said. He loved the cartoonists and cartoons of his time, including Will Eisner, and Milton Caniff and his “Terry and the Pirates.” Johnson had access to Life, Ebony and Jet magazines, he said.

“I always have everything around me that I need to do art,” he said. “There’s no shortage of things available to me at any time no matter where I am. Little kids are like that because they can play anyplace.”

Some of his later drawings bore the memories of his childhood: A blacksmith shop. A sign on a post with the words “The Lord is Coming.” Church revival tents. Swimming in the “filthy” Delaware River, and fishing and catching “big snapping turtles” there, too. Mr. Mosley and the men who cooked half a pig in a fire pit overnight for a barbecue the next day.

Johnson attended Bartram High School where he took classes in commercial art, graduating in 1955. He won an award for a sculpture in the annual Gimbel Department Store Art Exhibit. While at Bartram, he and four other commercial art students formed an arts league.

After graduating, the league planned an exhibit of their works, including paintings, watercolors and sculptures. One of the students was a piano player for Lee Andrews & the Hearts whose record “Long Lonely Nights” was a hit in 1957. All five worked other jobs, Johnson at the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot. They told a reporter that the art fair would be held at St. Cyprian Episcopal Church in Elmwood where the Rev. Paul Washington was pastor, but they did not have permission yet.

Johnson studied at the Samuel S. Fleisher Art Memorial, the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts) and the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine. He earned a master’s degree in human services from Lincoln University in the 1980s.

His artistic influences

Johnson “absorbed” the work of other artists, he said. Horace Pippin was one of his favorites because of the feeling the artist imparted, which reminded Johnson of his early home life. He was especially fond of Pippin’s “Giving Thanks.” Johnson’s mother cooked on a huge black cast-iron wood-burning stove and heated a heavy metal iron to press garments. The family ate at a large kitchen table, read newspapers and talked about politics and issues of the day.

“Like Pippin’s kitchen, my childhood home was filled with handcrafted items, quilts, blankets, rugs, crocheted and knitted doilies, clothing and the like. Horace Pippin’s paintings in the Barnes collection illustrate for me the descriptions and stories told to me by my grandmother, who was born in the 1890s, about her childhood. I see in the composition and palette of Pippin a striving for harmony and security. Building a wall from which he can be an observer and recorder, simultaneously exposing his vulnerability and sensitivity to the viewer’s gaze. A desire and need forged in migration, war, and existence in a nation where terrorism still confronted African Americans,” Johnson wrote for his art residency at the Clay Studio in Philadelphia from 1995-2001.

Johnson’s sensibilities were honed by both visual artists and writers, including Ralph Ellison and Wright.

“Ben Shahn and Upton Sinclair, that whole milieu gave me the idea that art was about being aware of society, being aware of people and being involved in that,” he said. “That’s what I thought art was. I never thought it was just being able to do a pretty picture.”

He also was inspired by the work of “Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley and other African Americans whose art is rooted in improvisation and process. The urban collages of the streets of Harlem by Romare Bearden, the intense urban paintings of Beauford Delaney and the artists of the Ashcan School. Most importantly, the work of Philadelphia painter Louis B. Sloan, a great influence in me.”

Art as a form of activism

Johnson felt that artists should be activists, not isolationists, and become involved in the community, especially with children. He told interviewers that he participated in the Black Arts Movement in Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the Black Panther Party (He didn’t elaborate. That’s one of the areas I would have explored with him). He was friendly with members of the MOVE organization and its founder John Africa, he said. He recalled when artists were among the protesters who marched to force Girard College in Philadelphia to open its doors to Black children.

“Much of that art was concerned with the pressing social issues of the time and jazz was seen as a structural and inspirational component in the creation of that art,” he said. “Artists such as Ben Shahn and Jacob Lawrence were artists who inspired me with their paintings dealing with social issues.”

“At that time, I could not afford much in the way of art supplies,” he added. “However, I was very aware of the Arte Povera Movement and the work of its artists. The art of impoverished materials was an important aspect of the movement. Necessity and awareness of constructivism and assemblage encouraged me in the use of found objects and materials from the urban environment to create glaze and texture in my work.”

Johnson acknowledged the racism in this country and how it undermined Black people. “The conditions people are living under now are directly related to the aftermath of the Civil War,” he said. “You remember Jim Crow was instituted then. “Birth of a Nation,” that so-called masterpiece of racism by D.W. Griffith, came out. That disgusting piece of crap. The way people are living now is not an accident.”

He was also worried about where the country was headed and its effect on today’s children.

“Even during the ‘50s and ‘60s when I was really crazy, still some place deep down I believed in America and that’s been shattered,” he says. “How do children feel? I grew up during the Second World War and the atomic bomb and all that fear. I know how that shaped my life and my perception. I can only imagine what’s happening to young people.”

What he tried to accomplish with his art

“I came to a conclusion long ago in my studies, while I was impressed with African art, I was far more impressed with African American art, particularly vernacular art, putting things together,” he said. “I respect the African-American vernacular art. In fact, I respect folk artists in general – white or Black or red, green, or yellow, (who) use materials at hand and make in a really creative, really make something that’s outside the (norm),” he added.

Johnson described himself as an “urban expressionist.” He pulled his images from the photos he shot in the camera dangling around his neck, the people on the streets, the rowhouses, train cars, advertisements on buildings and graffiti. “Little fragments of thoughts and little ideas from other projects make me realize sometimes I can collage them into a new form, a different form of expression,” he said.

His application of art extended beyond his studio. In 2003, he directed a neighborhood project at the St. Frances Academy community center in Baltimore. He taught community people, students and nuns to create a ceramic mosaic mural depicting Mother Africa, and civil rights leaders and symbols. It was titled “And Still I Rise,” after Maya Angelou’s poem of the same name. He saw art projects like this as a “healing force for social ills,” an article noted.

Johnson’s art is as layered as life, pieces on top of pieces that evolve into something we can’t control. “Most of my work, one day when they X-ray those bad boys, they’ll see that there’s more layers under those suckers than a little bit,” he said. “It’s to not know and see what evolves. For me, art is about endless exploration.”

Johnson doesn’t seem to have exhibited extensively for the first 30 years of his life. Likely because he came into his art at a time when white galleries and museums refused to show Black artists. “I was from the older generation when it was really difficult for artists of color to be shown in Philadelphia, period. We had to agitate and fight for that. So there was a lot more involvement (by artists) in the real world,” he said.

In 2019, when Trunc boutique in Philadelphia opened to highlight emerging and veteran artists, he – as well as artist Dindga McCannon – was among them. “When I was young, I used to walk in some places, and they would act like I was sticking them up. I would show them my work and they wouldn’t believe I made it,” Johnson said. “Stores like (Trunc) are great because IKEA’s not going to pick me up.”

In 1966, he was one of 12 local artists in an exhibition of contemporary Black artists at the William Penn Memorial Museum in Harrisburg, PA.

In 1969, he was selected for a major exhibit titled “Afro American Artists 1800-1969” sponsored by the Philadelphia School District and the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center. In 1988, he was part of a four-person exhibit at the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum in Philadelphia. Afterward, his works appeared to have been shown more often.

He was a resident artist at the Clay Studio from 1995-2001, where he taught at its school and the Claymobile, its outreach program; the Barnes Foundation in 2019, and the New Community Corporation (NCC) and the Montclair Art Museum in 1997 in New Jersey, where he worked with residents and students to create three-dimensional artworks for the public courtyards at NCC. At the time, he was an art therapist working with at-risk teens, as well as teaching workshops at Village of Arts and Humanities in Philadelphia.

Johnson visited Israel in 1999 and exhibited at the Tirza Yalon Kolton Ceramic Gallery in Tel Aviv. In 2015, he was selected for a group exhibit of Black artists titled “We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s” at the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia.

“I want history to see me as an artist who had something to say, and saying it in an elegant way,” Johnson said. “Like Thelonious Monk, playing my own notes.”

i put his painting in the black art auction to establish an auction record for leroy… he was happy that i did, i didn’t tell him and i wanted it to be a surprise…needless to know he would pass a month later…we were friends for 20 years and we sent many moments talking about art and life….i miss my dear friend…wm dodd

Hi Dr. Dodd. I’m so happy that you submitted the painting. It is very important for people such as Leroy to have a trail for potential purchase and sale of his artwork, but to also to raise his profile and highlight his talents. It seems that a number of people knew him; I regret that I was not one of them. Just talking to him for the few minutes I did on the phone left me with the feeling of a man who was very endearing. I did mention to him that I learned of him when his painting turned up at Black Art Auction.

Sherry