They were three teens from Black neighborhoods in North Philadelphia where graffiti was more prevalent than Picasso. Like most children in insular neighborhoods, they never much ventured outside their area, hindered by little money and forced segregation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Barkley L. Hendricks, James Brantley and Ed Jones had the artistic talent but lacked “polish,” as Hendricks would describe himself years later. Their high school art teachers, including Bessie Ruth Bridges, honed it. “There was a lot of talent there that had never been cultivated,” says Bridges, who taught all three – Jones, first – at Simon Gratz High School.

Bridges obtained permission from parents and her principal to take her classes for art majors to visit museums.

“I felt they didn’t have enough knowledge about the art in the city,” she says. “We would get on public transportation and go into Center City. We’d go to the art museums. I would take them through there and they would see the styles of art, different kinds of art and we’d talk about it.”

She also told them about the million-dollar values of some of the works in the museums, which was amazing to them. “I was just opening their eyes to the possibility of making a living as well as teaching,” she says. She tried to instill in them “how to express yourself and learn the different styles of art so you would know which way you wanted to go.”

Hendricks would become an internationally known artist whose life-size portraits of Black men and women with attitude changed the art world and its perception of people who shared his skin color. After Hendricks’ death in 2017, prices for his works skyrocketed into the millions of dollars on the secondary art market at auction.

His “Mr. Johnson (Sammy from Miami),” painted in 1972, sold for $4 million at Sotheby’s in New York in December. At Sotheby’s a month earlier, his painting “Jackie Sha-La-La (Jackie Cameron),” which sold for $48,000 in 2010, went for $2.8 million. That painting was from 1975.

“Barkley was a hard worker and he was an excellent artist,” Bridges says. “He had talent. I just helped him develop it.”

Brantley is a figurative painter whose works are delivered in an impressionistic style. Jones, too, is primarily a figurative painter but also does abstracts. I interviewed Jones several years ago after picking up one of his high-school paintings of Victorian homes in North Philadelphia at auction. The painting won an award in 1960 for the then-17-year-old. It was submitted by art teacher Hilda Schoenwetter, who was a landscape artist. Jones is featured in my book “ART WITH HEART: How I Built a Sweet Collection by Buying Cheap at Auction,” available at amazon.com.

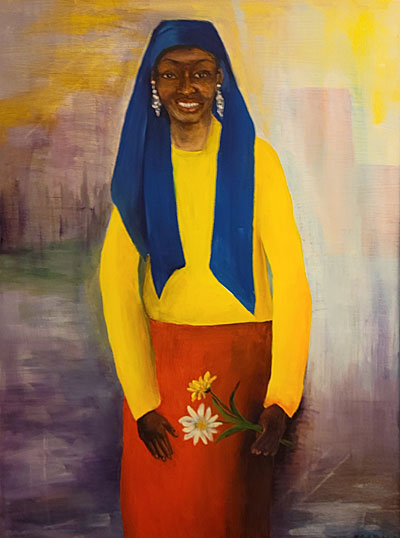

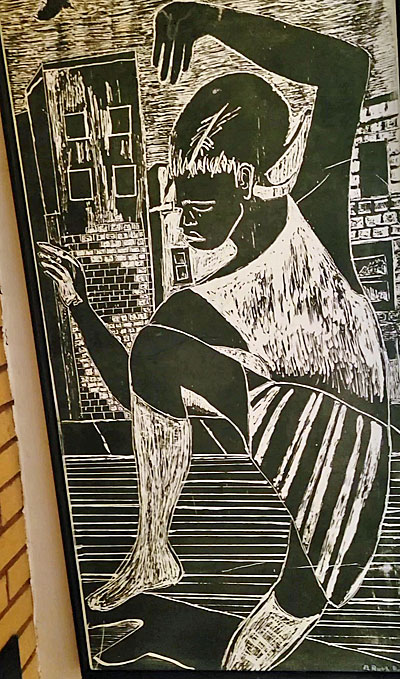

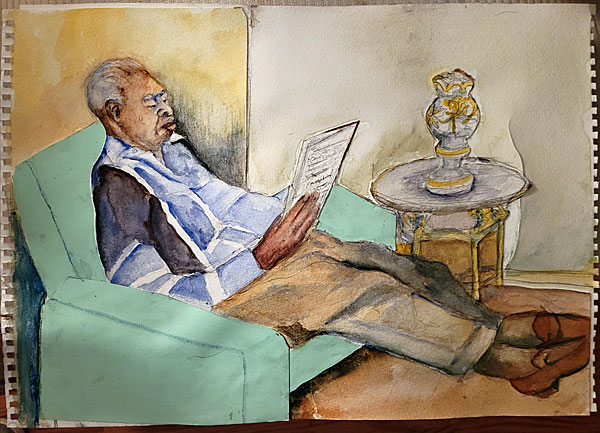

Bridges worked in the public schools for more than 30 years, retiring in 1986 as an art supervisor for the Philadelphia School District. She’s been painting for more than 70 years and is still at it at age 94. She has no studio – never has – but instead sets up her easel all over her home, mostly in her spacious kitchen. To produce prints, which can be messy, she goes to the basement.

You won’t recognize her name or likely see it in any anthology. You won’t hear much about teachers like her who mentored and pushed great artists toward their greatness. They are people in the shadows, among the many local artists across the country who paint because they love to and don’t worry much about being noticed.

Bridges paints what she feels and when she feels like it. She works in watercolor and oil, and she makes serigraphs, woodblocks and other prints.

“I just painted to please myself,” says Bridges, who lives with her husband Charles, a retired doctor who was teaching science in public school before deciding to go to medical school in his 30s. He became a doctor at age 40, he says.

“I don’t go around trying to get anybody to be impressed over my work,” Bridges says. “I just work to please myself. If they don’t see it, that’s their problem.”

Bridges as art teacher

She was among the teachers who gave young Black students their first formal art lessons. Bridges broadened their knowledge through the museum trips, taught them the fundamentals in class, and later in her career, played Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony” to train students to use the creative side of their brains, she says. Her students kept sketchbooks of their drawings.

At the museums, “I was exposing them to the history of art and how the artist started out and how some of them had never been to art school. That’s Van Gogh and people like that. And I would talk about them and how they lived, how they were very poor. Most of them died poor but they became famous afterward.”

Bridges also encouraged them to be original. “Like the Guggenheim Museum (in New York). The reason he (Frank Lloyd Wright) was so famous was because he had a new idea, a new way of working and a new way of expressing (him)self.”

Brantley remembers her and her teachings fondly. “She was very very good at representational training in terms of realistic paintings that we were really inspired to do,” he says. “In her class, we were given the opportunity to expand our own individual voices in terms of how we saw the world and how we could translate that in an art form.”

He credited her with helping him and Hendricks get into the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), where they enrolled in 1963. At the time, PAFA was just starting to admit Black students in numbers larger than one at a time. He says they were in her class in the early 1960s before heading off to the academy, where they each received a small stipend.

“She got these kids from the inner city to go down to Center City Philadelphia to one of the oldest most influential art institutes in America,” he says. “Had it not been for Mrs. Bridges, Barkley and I would not have attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. She was responsible for putting our portfolios together, getting 40 representations of artwork down there at the academy.

“We owe a lot to her.”

Bridges recalled Hendricks’ mother coming to her. “I encouraged her to encourage him,” she says.

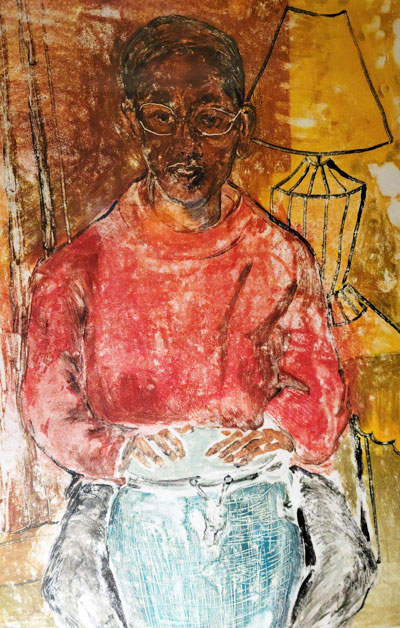

While at the Academy, Hendricks painted a portrait titled “My Black Nun” in 1964 in his famous style. In 1968, Brantley painted a self-portrait titled “Brother James” in the same style.

In an interview in 2017, Hendricks spoke of Bridges’ class:

“I was born an artist, and school was like a gem-polishing experience. I was a gem and I needed some polish. … I remember vividly, a good friend of mine whose brother was a bit older and he borrowed his brother’s Coltrane record and brought it into class. And we were to (make) some illustrations from that particular pressing, which always comes to mind (as) it’s one of the seminal musical pieces that still sticks with me. (So) being inspired to do record album jackets (for) music that I like. And starting illustrations, to develop basic skills, were part of the areas that I experienced in I think, it (was) Ruth Bridges’s class. And then I had another teacher whose name was Mary Higgins and she helped to give me a free rein in terms of direction, and when I got home, I followed through with the development of my representational skills … I stuck with realism, or representational imagery in the face of so much of the commotion of abstraction (because) I saw abstraction as not high enough.”

Began sketching as a child

Bridges is Philadelphia born and bred. Born on March 20, 1927, she grew up in Southwest Philadelphia with parents who came to the city during the Great Migration of Black folks from the South starting in the 1920s. They had lived in Winnsboro, SC, just northwest of the state capital of Columbia. In Philadelphia, her mother was a housewife and her father worked at a chemical plant. She was one of six children.

She was named Bessie after her mother. She signs many of her works as B. Ruth Bridges.

She recalls sketching as young as five years old. “Lots of times we used to get together as children and sit down and start sketching,” she says.

At Thomas McKean Elementary School, she did drawings for the bulletin board, and she was head of safety patrol. At Bartram High School, she was the one called on – and she volunteered – to create drawings for the hallways at holidays.

Her high school art teacher discovered her, she says, and taught her to paint flowers in watercolor. “It just came so easy. I didn’t think about it,” she says. “The teachers were all amazed.”

Bridges says she received a scholarship to the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts) where she learned printmaking. She says she majored in ceramics and was set to go to The Cooper Union School of Art in New York on a scholarship, but she didn’t have the funds to live on in the city.

She got a certificate from the College of Art and headed to Tyler School of Art at Temple University, where she received bachelor degrees in arts education and fine arts. She later received a master’s in arts education from Tyler.

After graduation in 1954, she was hired at Gratz and stayed for nearly 25 years. She left there to work at the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA), where students had to demonstrate their talents to be chosen. “The students who came there were really talented,” says Bridges. “I mean outstandingly talented. I taught watercolor and still life.”

She says Hendricks visited her often while she was at CAPA. Bridges taught there for five years before becoming a supervisor of art with the school district and then retiring in 1986. She says she has always helped students get scholarships to her alma maters.

For a while, she put up a tent at art shows, particularly in Haddonfield, NJ, bringing her son along to hang paintings and set up easels for displays. She sold “quite a few things,” she says. But she didn’t much like the process. “I got tired of that.”

Bridges was not one of those artists who was out there hustling to sell her works. “I didn’t try that hard,” she says. She is represented by the Moody Jones Gallery in Glenside, PA.

Teaching adults to paint

Bridges used Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony” to sparks students’ creativity, whether they were schoolchildren or adults. She also added relaxation exercises using their arms and fingers. “‘Cause you have to learn how to use your imagination,” she says.

She starts by teaching them to mix colors (“If you can only afford three colors, you can make color from those three – red, yellow and blue.”) and how to capture street scenes by learning perspective (keeping images in the forefront large and in the background, small).

Once, she taught an adult art class at her church to help raise money for repairs to the conference hall. “They didn’t know nothing about art at all. They didn’t even know how to mix colors when they came in there,” she says.

One of her senior-citizen students was Frank Meekins, a member of her church who was “extremely talented,” she says. “I liked Frank because he had a style that was original. Everything looked just wonderful, came straight from his own imagination. He did a lot of street scenes. I taught him how to do street scenes, but it was his.”

Meekins was born and raised in Philadelphia, worked at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and knew very little about painting before the class.

“When I went to her class, I learned how to use paint,” says Meekins, who at age 97 lives in Nashville, TN, near his daughter. “She taught me perspective, quite a bit about art. I could draw a little, but I didn’t dwell on it. … We started off with still art, flowers, street scenes, houses, buildings. I became a little proficient at it with her tutelage.”

Bridges brought photographs of street scenes to class, he recalls, and he based his paintings on them.

Now, he paints to keep himself occupied at the retirement home where he lives. “It’s gratifying because you’re doing something,” he says. “In these homes you got to keep yourself busy or you’ll go crazy. So I do a lot of artwork here. As a matter of fact, they have an art class here and I was asked to assist,” but the class was cancelled because of the COVID pandemic. He has not sold any of his paintings, he says, but has hung them on his walls and gifted them to family.

Bridges taught the class for about four or five years, charging $100 for five to six weeks of classes in the dilapidated hall. “I got enough money to redo all the walls. It had holes in them. Insulated the wall, fixed the ceiling and we went to kitchen and fixed it.”

A truly inspiring story of an amazing teacher who touched future amazing artist

My name is Gerald branch, I was a student of Ms. Bridges at Simon Gratz during the years of 1965-68. She inspired me to teach art in Philadelphia and to serve as a principal across 37 years. I have been an exhibiting artist for more than 40 years and was very much influenced as the others mentioned in this article. My Instagram account is geraldbranchart. I would love her to see the influence she had on my work, strongly encouraging me “don’t be afraid of color.” I would love to speak with her if I could.

Good afternoon Sherry,

I would personally like to thank you for writing this beautiful article about Mrs. Bessie Ruth Bridges. She deserves this. Sherry thank you for Introducing me to Mrs. Bridges work. There are so many more artist like Mrs. Bridges around the country who don’t get the credit they should. Keep doing what you do and keep educating the general public about these undervalued artist.

Best regards

Donnell Walker