Benjamin Britt was always a mystery to me. He seemed to be on the periphery of my thoughts, never fully formed, almost an illusion.

I would hear his name in snatches, but it was hard for me to conjure up an image of him or any of his works because I’d never seen much of either. I can recall only once that a painting of his came up at an auction I attended. A fellow auction-goer told me about an abstract on a wall near the door of the auction house.

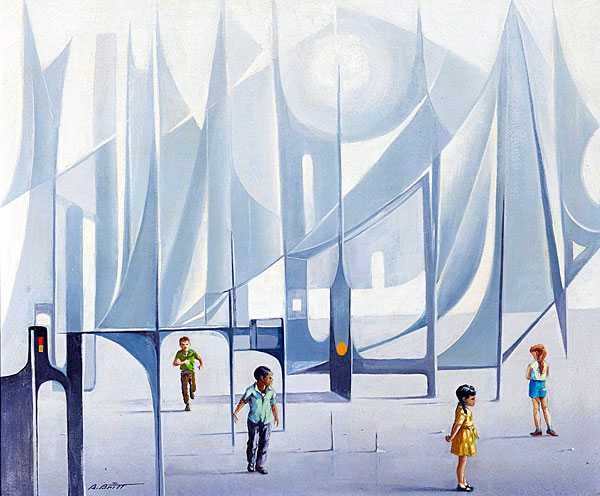

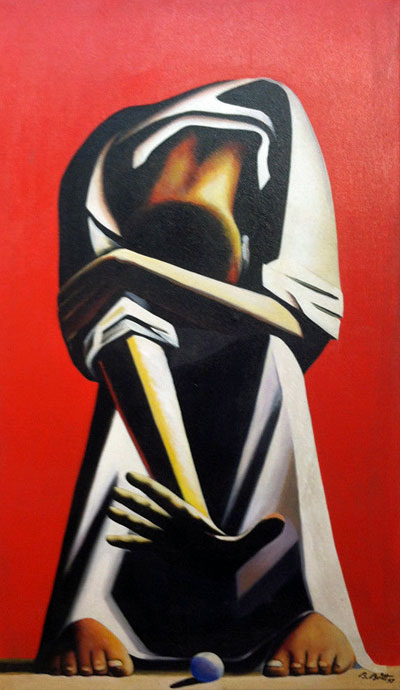

I acknowledged it but didn’t rush over for a look-see. As I was leaving the auction house early, though, I stopped by to view the painting. It was a small abstract with Britt’s signature (B. Britt, the “i” always dotted with a tiny circle) but it didn’t appeal to me. I’m sure this auction-goer bought it for a steal; no one else likely knew Britt’s name.

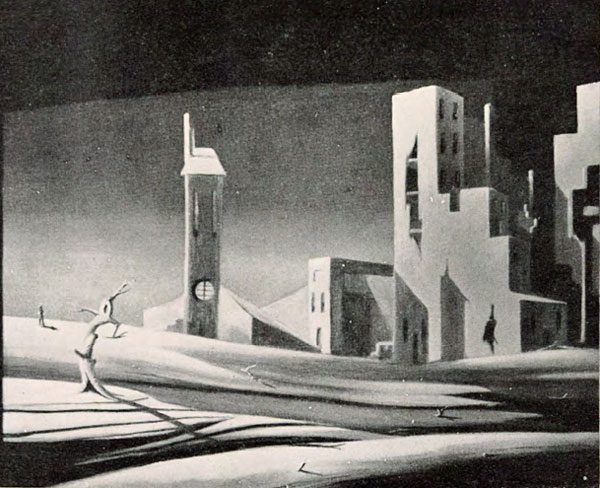

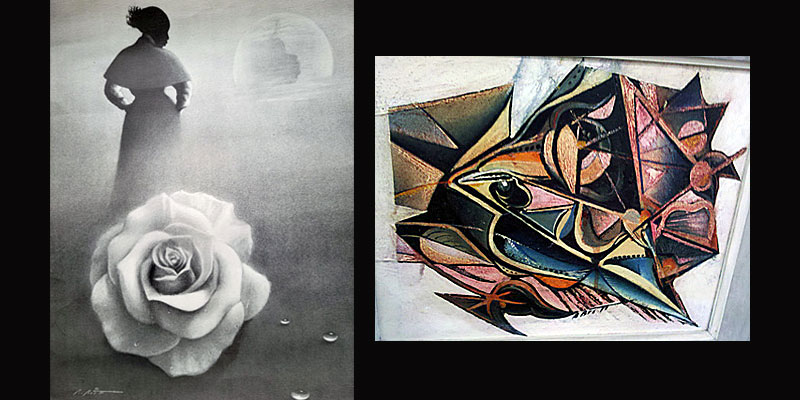

A few years later, I picked up a stack of unframed reproduction prints at auction that included one by Britt (and artist Andrew Turner, both signed to a fellow named Chester Walker Jr.). Britt’s print had no color, just a grainy gray background with seemingly disconnected images.

It was surreal: bottom left, an oversized rose with tiny water droplets; bottom right, floating penny-size water droplets; top left, the full figure of a woman, her back turned; top right, silhouette of a face in the moon.

Whatever did it all mean? I wondered.

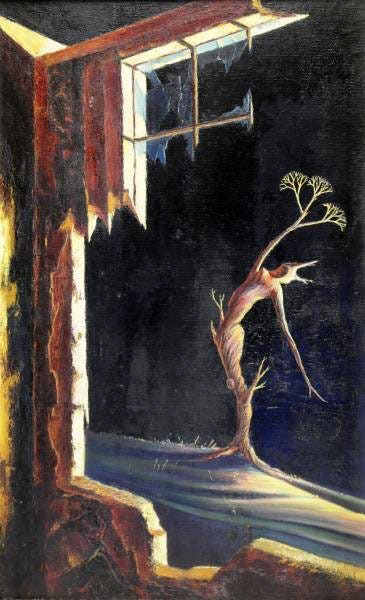

Britt died in 1996. He couldn’t answer for himself, but his son told me that Britt favored surrealism and abstract art.

This is how the Tate Museum in Great Britain explains surrealism to kids on its website:

“This was an art movement where painters made dream-like scenes and showed situations that would be bizarre or impossible in real life.”

And disconnected, as in the Britt print. One of the most important painters of surrealism was Salvador Dali, who was Britt’s idol.

“He enjoyed the surrealism,” says Britt’s son Stan, 77. “Dreams would be a big part of the definition (of his works) but in the style of Salvador Dali. Later, more of the abstract like Picasso, but I think the Picasso period … was a shorter period.”

When Britt was young

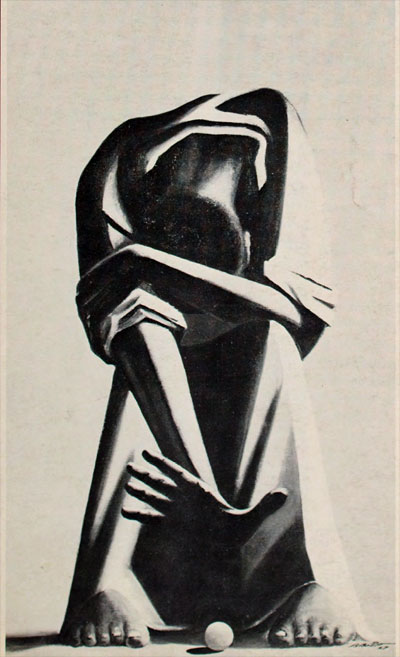

Stan says his father was influenced by the Bible verses that his maternal grandfather, a Baptist-minister, read to him as a young boy. Those verses would find their way into such paintings as “Wife of Lot,” “Yield Not” and “The Prodigal Son.”

In 1957, Britt won first prize for best figure painting in oil for “Yield Not” at the 16th Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture and Prints by Negro Artists at Atlanta University (AU), according to The Atlanta University Bulletin, July 1957. Britt’s painting was pictured in the publication. It was his first AU award, winning $300.

“He never forgot his grandfather reading the Bible verses to him,” Stan says.

Ben Britt was born in 1923 in the town of Winfall, NC, more a borough than a town with a population of less than 300 people sustained by farming, a lumber mill and the Norfolk and Southern Railroad. The town got its name Windfall after a windstorm took down its first building in the early 19th century. It incorporated as Winfall – without the “d” – in 1887. Today, the Winfall Historic District, consisting of several houses and buildings, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Back then, Winfall was a southern town in a southern state where Black Lives did not matter and laws made sure it remained that way. Today, Winfall has a Black mayor, who was elected in 1993.

Escape to Philadelphia

Stan does not recall his father mentioning much about his life in North Carolina, but he did learn how he ended up in Philadelphia. Britt’s mother and father left the state with him, his brother and sister when he was about 6 or 7 years old, along with his grandmother and other members of the family.

“My father’s father on my paternal side had an encounter with his (white) employer and hit him in the head with a shovel and basically killed him,” says Stan. “In North Carolina, the Ku Klux Klan was trying to find him because he went into hiding. A doctor that my grandmother worked for told her she needed to leave town because they would come after her and the kids to force him out of hiding.”

Her employer suggested that she take his last name to hide her identity. His surname was Britt, and she took it as her own.

“Not until late in my life, probably in my early teens, (was) there any contact with the family there in North Carolina,” Stan says. He recalls that on the way to visit his mother’s family in South Carolina, the family detoured to Hertford, NC, near Winfall, to visit his father’s family.

Although the experience altered the family’s life – Britt never saw his father or grandfather again – it did not influence his father’s art, says Stan. He did miss his grandfather’s Bible stories.

The influence of artist Samel J. Brown

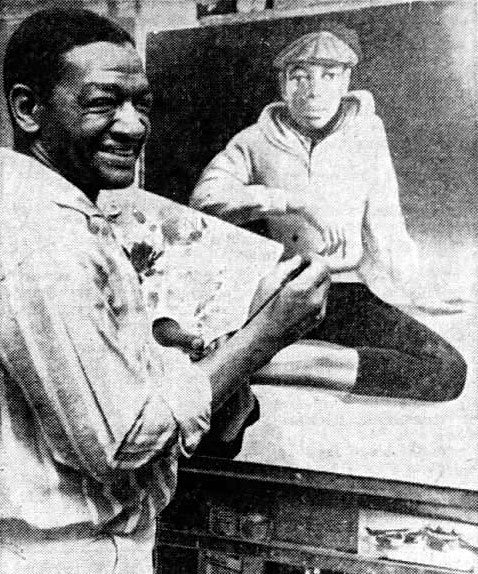

In his new hometown as a teen, Britt attended the newly opened Dobbins Technical High School where he met his future wife Marjorie, who was in the cosmetology program and later became a beautician. Britt was taking classes in commercial art, and one of his teachers was African American artist Samuel J. Brown.

Brown taught in the Philadelphia School District for more than 30 years. He, too, was born in North Carolina, Wilmington, in 1907 and moved to Philadelphia.

Stan believes that his father realized that he could become an artist while studying under Brown. Britt believed in Brown so much that when Stan was a student at Dobbins studying architecture, he urged him to seek out Brown for advice.

“He sort of dabbled before,” says Stan, “but (the) early successes he had at Dobbins with Mr. Brown … gave him the confidence that he could be an artist.” Another influence was the white instructor who taught him commercial art. Both Britt and his brother Willis were commercial artists; for years, the brother created illustrations for the Veterans Administration.

During a Black History Month program at a Millville, NJ, school in 1994, Britt told students that he had wanted to be an artist since he was 9 years old. “We had an artist come to my class and he showed some of his abstract paintings on stage and I said, ‘Shucks! I can do that,'” he said, according to the article.

At a school program in Bridgeton, NJ, about five months before he died in 1996, he mentioned that his grandmother in the 1930s had showed members of her church some drawings he had done of family members from photos.

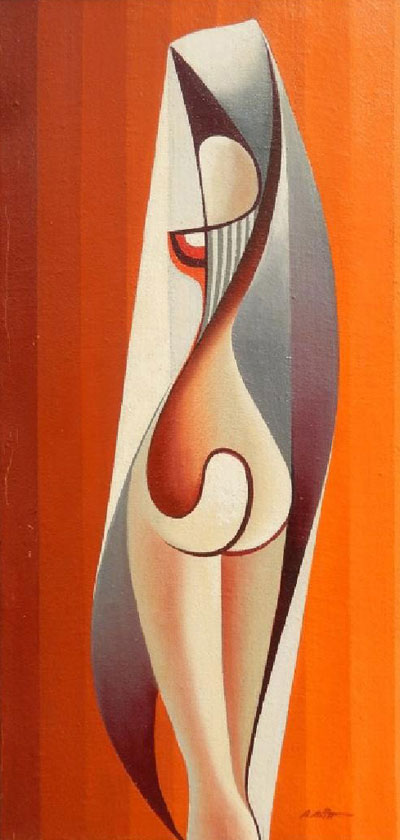

Phases of Britt’s art

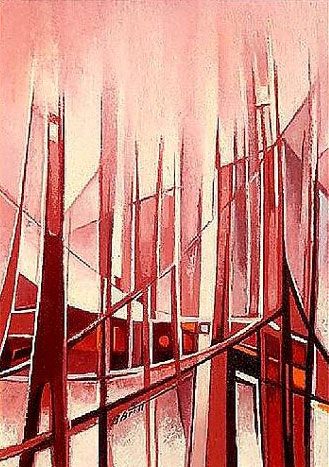

Stan says he has original artwork from each period of his father’s artistic life. The surreal painting “Pink Sand” is “a favorite because it’s the earliest painting I know of my father’s.”

(Britt’s “Pink Sand #2” won Atlanta University’s Purchase Award for oils in 1958, chosen by popular vote of those attending the month-long show, according to the AU bulletin and mentioned in the NAACP’s The Crisis magazine. The prize was $100.)

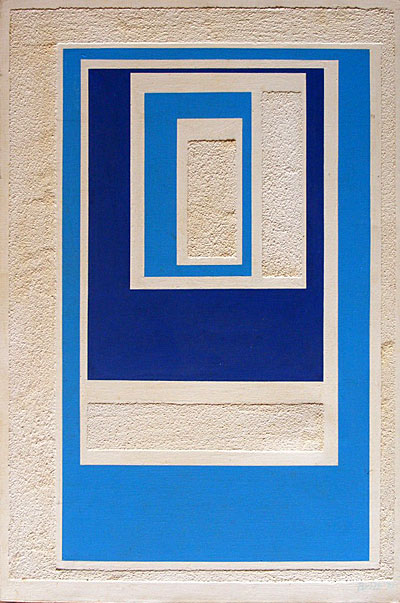

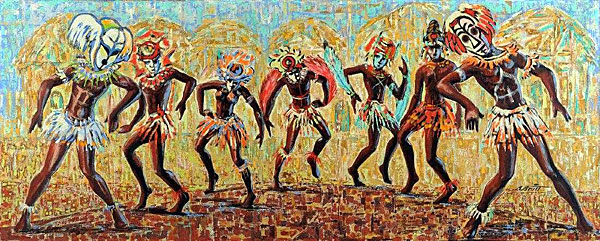

In the painting “Environment,” Stan says, Britt inscribed sayings on a wall pertaining to preservation of our natural resources. Britt’s abstract “Chicken Bone Beach” is based on the Atlantic City spot where African Americans sunned and gathered when whites-only beaches at the Shore were closed to them.

His father’s last period was “illustrative,” Stan says, when Britt produced figurines, portraits and commercial works to pay the bills. While he sold some of his art, Britt could not always depend on the sales to fully support his family.

“He did a lot of portraits, which I don’t think he enjoyed,” says Stan. “But that was another means of income.”

When Britt finished high school, he created artwork for ads for a local drugstore. He also drove a cab and worked at a company that made paper, which worked for him because it gave him access to watercolor paper, says Stan. He worked fulltime and painted in his off-hours. In a 1967 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Britt says he became a full-time artist when he opened his first studio in 1963. Speaking to the Millville schoolchildren in 1994, he said he had only been “recognized” as an artist in the last 10 years.

“And that’s simply because I’ve outlived a whole lot of other artists,” he said.

Britt expounds on his art

In the Inquirer article, Britt noted that he did what many artists avoided; he created paintings for clients to match their home décor. He saw it as a means to an end: allowing him to make money so he could paint what he loved.

“‘I would rather give in to this point and paint than work eight hours at a job I detest,’ he said. ‘I guess you could say I’m using practicality with the arts and that makes me a little different. Why can’t art be a business as well as esthetic expression?’

Britt, who lives above a small studio he opened recently at 7130 Germantown Ave., believes his custom paintings serve a need. ‘You’d really be surprised how many average people want original art works,’ Britt noted.”

“‘I’ll sit down with them over a cup of coffee, get some idea of their tastes and attitudes, the atmosphere of their home and see the wall on which they are going to hang the painting. Then I key the painting to that. What they are getting is a decorative wall piece and an original painting that encompasses my ideas and symbols.'”

Here’s more insight on the artist from the article:

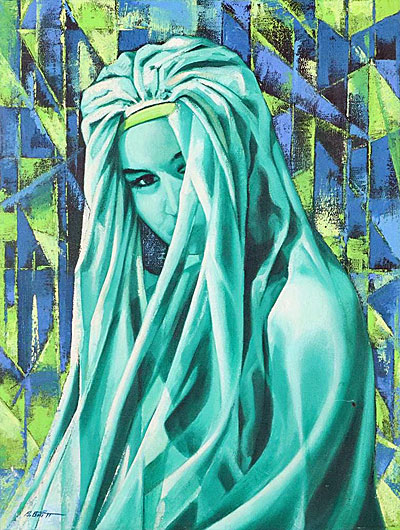

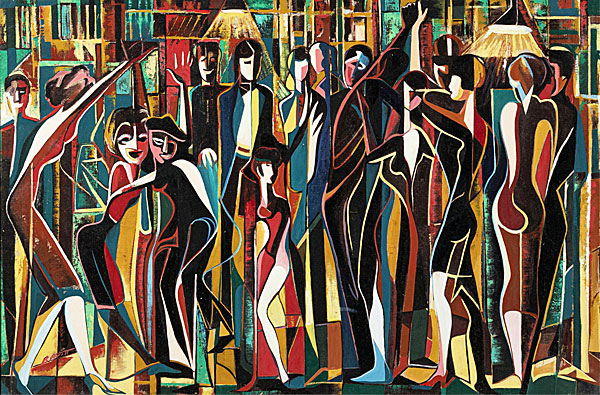

“Britt’s abstracts and surreal works are bright paintings which reflect what he feels and thinks. Often they are social commentaries. They are always statements on the things he has seen.

‘Soul Brothers’ is an abstract depicting a three-faceted face. The facial segments are black, white and red, representing Caucasians, Negroes and American Indians.

For Britt, the painting signifies the ‘thin line’ between the three. (‘They all think and feel and love and die; The only difference is their color,’ he said.)

Frequently something in a painting he’s doing suggests another one. He then goes to another canvas and gets the basic idea down (‘like taking notes’), then comes back and finishes it later.

“Making notes” is one of the reasons he always has three or four paintings going on at one time. Another is production.

This is partly because he has to produce to make a living and mostly because he’s ‘happiest when I’m in front of an easel.’

‘This is life to me and if I had to give it up I might as well give up living,’ he said.”

Britt’s schooling and exhibitions

Britt studied at the John Hussian School of Art, the Philadelphia Museum School of Art and the Art Students League in New York, according to a July 2, 1996, obituary in the Philadelphia Daily News. Along with oils, he also painted in charcoal and won prizes for his artworks, according to the 1967 Inquirer story.

He exhibited in shows in both Philadelphia and New York, his son says. He recalls his father participating in an exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1950 with his painting “Pink Sand.” Practically every year, he participated in the Rittenhouse Square Art Show, and his works were also shown at the then-named Afro-American Museum in Philadelphia, says Stan. He also participated in many group and solo shows.

He created a double portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a minister and civil rights leader that was hung in the auditorium of Joseph Pennell Elementary School in 1969, according to his Inquirer obituary.

In 1969, Britt was among 100 African American artists featured in the exhibit “Afro-American Artists 1800-1969” by the School District of Philadelphia and the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center. In 1973, he was included in a directory of African American artists by art historian Theresa Dickason Cederholm for the Boston Public Library. Its aim was to recognize African American artists who were ignored by and excluded from the mainstream art world and art history.

He also exhibited in Aesthetic Dynamics’ “Afro-American Images 1971” in Wilmington, DE. The Delaware Art Museum and Aesthetic Dynamics are re-creating that exhibition, spearheaded back then by artist Percy Ricks, which included 130 artworks from 66 national and local artists. It runs from Oct. 23, 2021, to Jan. 23, 2022.

He taught at the Wharton Center in North Philadelphia, YMCAs in Germantown and Center City, a Salvation Army branch and the Kensington Neighbors United Civic Association, according to his Inquirer obituary.

Artist Gladys Crampton told the story of how Britt taught her to use color. She was having a hard time painting bricks, so he told her to walk along Germantown Avenue and look at the bricks. “And when I came back I felt as though I could lay bricks. … Things weren’t told to you. You were given direction,” she said in a 1988 oral history interview.

Britt talks politics and religion

Stan remembers his father as a quiet man who talked politics and religion to him from the time he was in his teens. “Mentally, he was very much involved in politics. The idea of leaving the country with Marcus Garvey was very attractive to him.”

Although Garvey’s Back to Africa movement appealed to him, Britt never traveled outside the country except for the time he was in the Coast Guard during World War II in France and England. Traveling to other countries was always a dream, which he later shared vicariously through Stan’s travels.

In the 1960s, Malcolm X was preaching separatism because he didn’t believe that racism could ever be eliminated in the United States. Before he was killed in 1965, however, he began to embrace what he saw as the true tenets of Islam: the universality of man.

Britt “admired what Martin Luther King was doing but he had a much stronger affinity towards Malcolm,” says Stan. “He thought fighting back with white people was more important than the nonviolent position.”

A socialist, Britt was also troubled by how his socialist friends were harassed by the government, with some even arrested, says Stan.

“The whole experience of being run out of North Carolina is the thing that sorta pushed him in that direction to looking at another option,” he says, “because clearly for him and his experience, the existing political system here had failed. I think that’s what made that all very attractive to him.”

Britt introduced his son to the Koran but never embraced Islam as his religion. He studied religions and seemed to lean more toward Christianity after reading that Muhammad wrote about Christ in the Koran, says Stan.

“Even though he would talk about the Bible, he would talk to me about things in the Bible and do Bible paintings he never went to church,” says Stan. “He read both the Bible and the Koran excessively but as he would say he would never participate in organized religion.”

Living with Britt the artist

Stan often watched his father paint, something he very much wanted his sons to do. “He spent a lot of time getting my brother and I into drawing and painting and watercolors, probably I guess from the time I was able to hold a pencil,” Stan says. “As fairly young kids, he would drag us around to different museums, both in Philadelphia and as well as New York.”

When he was young, his bedroom was his father’s studio. “The easel and all the paintings were in my bedroom, which I feared because at night it looked as though many of those faces were coming alive. And I remember crying out to my dad about could he turn the paintings around. I knew all those people were looking at me in the dark.”

Stan did not become an artist, choosing instead a different artistic route. His parents separated around 1961, and his mother sent him every summer to visit his uncles, both carpenters, in either South Carolina or Virginia to get him away from the gangs in Philadelphia. When he was around 12 or 13, he was working with one uncle on a job site in Newport News, VA, on a hot day when a white man drove up in a “nice air-conditioned car.”

“Uncle said, That’s the architect. He’s the one who makes all the drawings that we use to do what we’re doing.” That night, his uncle showed him the drawings. “You should be able to do this because you’re pretty good at drawing,” his uncle told him. “At that time we were always drawing because that’s what my dad had us doing … and I was not a bad math student.”

“That was sort of my first introduction. I thought before then that I really wanted to be a sculptor. My mother said, ‘I’m not going to suffer to send you to school to be another starving artist. I’ve already supported one starving artist, so you have to go to school where you can get a job.”

He got a bachelor’s of science at Drexel University in Philadelphia and a bachelor’s of architecture at Columbia University in New York. He was president and senior partner of Sultan Campbell Britt & Associates in Washington, DC. Today, he is semi-retired and finishing up some projects he had started.

I first learned of Stan after reading that he was the architect for the rehabilitation of the house formerly owned by African American artist Dox Thrash in Philadelphia. Thrash was one of the creators of a print-making technique called carborundum in the 1940s.

Remaining close to his father to the end

Stan recalls his father moving out of the family home in 1961. It was a couple years after he learned that Britt had another family: two sons and a daughter. Stan and the daughter even attended Dobbins at the same time, but he only learned of her from his aunt, another student at the school. He discussed it with Britt, who introduced him to the oldest of the other children.

Stan and that stepbrother remained close throughout their lives, and he had the same type of relationship with his father.

Britt was still painting up to the end of his life, using one of the bedrooms in his two-bedroom house as a studio, says Stan. He was found dead in his home in 1996, at age 73. “They found him in a chair facing the television with a half-glass of sherry,” says Stan. “So if he was sitting in the chair with a half-glass of sherry, then I know he went the way he wanted to go.”

Stan asked him often how he’d like to be remembered. “His response would always be, ‘I want them to say ‘damn, he looks good for his age.'”

My father Lawrence EL and Ben Britt was close friends and art associates. I am Lawrence EL son and was raised around Mr.Britt and stood beside him when he did several paintings. Mr. Britt lived upstairs in an apartment building with my Father Lawrence. My name is Salim Ali ibn El. My father was a artist as well. I set up a web site for dad’s artwork that has never been seenby the art world. Salim Ali ibn EL. I am a silkscreen printer. Mr. Britt introduced me to the art of screen printing.