I became acquainted with the works of artist Tom McKinney when I first started buying art from a framer before I discovered auctions. I bought a print awash in dark tones titled “Lazy Afternoon,” of three Black men sitting on stone steps.

Their scraggly faces and thin bodies told the story of lives worn down by too many hardships and too much booze. The faces also showed character, which gave them an element of dignity. It wasn’t a piece, though, that hung in a prime spot on my wall.

That was Tom McKinney then.

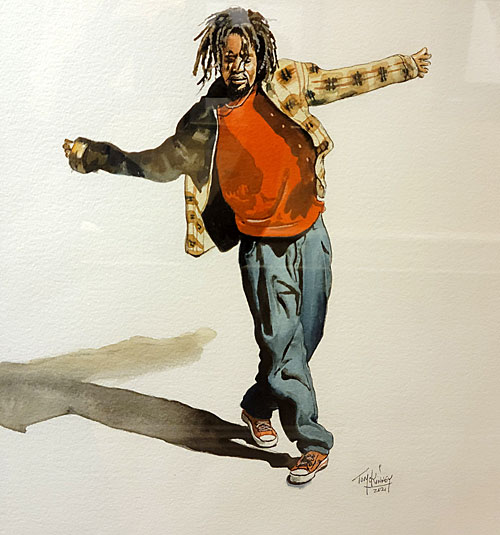

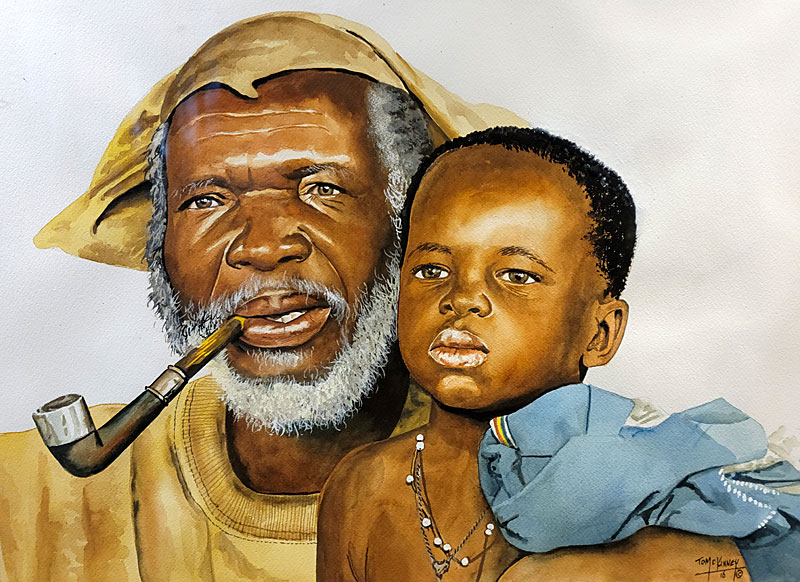

Today, he paints his everyday folks in flesh tones and clothing saturated with color. Thirty of his watercolors are in an exhibit and sale at the Rydal Park retirement community just outside Philadelphia until Sept. 1, 2021. It is one of several senior retirement communities where he has been selling his artwork these days.

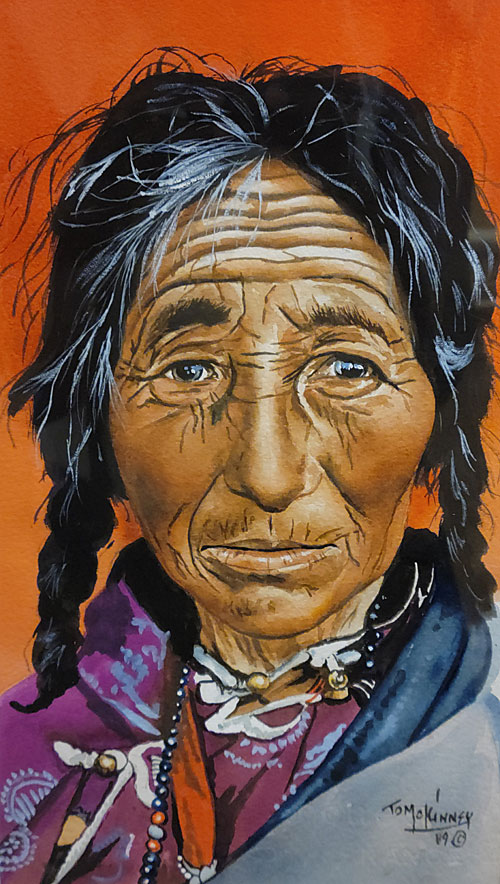

Off from the lobby of Rydal Park, McKinney’s watercolors line opposite walls along a hallway toward the elevator, forcing residents to stop and linger at paintings of children playing, people waiting to be vaccinated, men playing cards, cats and dogs, white people, Black people, Africans and a Native American.

These new works – all originals, he doesn’t do prints anymore – show an artist who has evolved.

“The difference is I grew,” says McKinney, 81. “A lot of people say, I have your work, and I’m thinking you don’t have the best work. But that’s all I could do then.”

“When I look at this particular show, I say you getting pretty good, man.”

McKinney’s “blossoming” – as he called it – occurred about five to 10 years ago, he says, after he began painting watercolors at the suggestion of his friend and fellow artist Joseph Holston. McKinney is a self-taught artist who learned primarily by querying other artists, studying exceptional works, trying new techniques that popped into his head and always generating new ideas. He has been painting for nearly 60 years,

“It’s like learning how to play an instrument and learning a certain touch,” says McKinney, a jazz lover. When one musician listens to another’s techniques, “you can’t do it right then, but you heard it and somewhere in the back of your brain, it starts to surface and all of a sudden, you hit it. You say, Yeah, that’s what I’m trying to do.”

McKinney says he has made a good living off his art. His works are in private collections, with most of his prints purchased by individuals at art shows from Maine to Florida. He has built a reputation along the art-show circuit, starting with Rittenhouse Square where he returned for 15 years. (A resident of Rydal Park owns three Madonnas that he bought from McKinney at a Rittenhouse show in in the 1970s.)

Also for 15 years, he was a fixture at the Virginia Beach Boardwalk Art Show and a few times at the Atlanta Fine Arts Show. He’s also done shows in Hawaii, California, at military bases in Germany and Alaska, and the Essence Music Festival in New Orleans.

He was one of 100 African American artists who participated in the exhibit “Afro-American Artists 1800-1969” mounted by the School District of Philadelphia and the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center in 1969. His painting was titled “Our World Today.” The exhibition – with catalog – was a premier event.

Bill Cosby has purchased about a dozen of his works, including a Count Basie that hangs in his Cheltenham home (McKinney saw it there recently on a newscast after Cosby was released from prison). Several of his pieces were on the sets of the TV shows “The Cosby Show,” “Frank’s Place” and “Bustin’ Loose” (not the movie), he says.

“I did all this myself,” says McKinney. “I had no idea how to do half this stuff. But I would call guys and say what do you do when you do so and so and so and so. A lot of people couldn’t believe I could make a living out of my art. And I didn’t hustle. I didn’t hustle.”

His narrative style of painting

McKinney says his works are in the style of Norman Rockwell, whose realist paintings presented everyday people living everyday lives. In fact, he sent a letter with a photo of one of his paintings to Rockwell in 1971, he says, and received a reply in a congratulatory letter that wished him success.

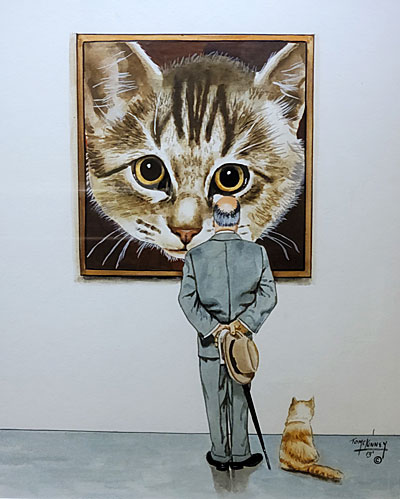

One of the paintings on the wall at the exhibit/sale is based on Rockwell’s “The Connoisseur,” of a man staring at a Jackson Pollock painting in a museum. In McKinney’s whimsical version, the man stares at the oversized head of a cat while a real cat sits at his feet.

McKinney is a storyteller in both his paintings and in his person. He speaks not in sentences but in anecdotes, spilling them out as naturally as he talks.

“I did a big (painting) of a lady. She’s standing with a short skirt on, and she got her hand on her hip and she’s looking up at a painting of Marvin Gaye. … The first person who saw it, this guy said, Man, I’d love to have this in my office. He said, I’ll be back and bring my wife. I say, Uh oh, brought his wife, she said, Umm, Umm (skirt was too short). … Then a doctor and his wife came to a show I did in Virginia. She’s walking around looking and she says, Honey, honey, come here, come here. She said, What do you think of that, and I guess he figured I better say the right thing, and he looked and he said, It’s nice, and then she explained to him the woman is for the guys and Marvin is for the ladies. She told him the whole story and I said, How’d you know that? She said, You tell your story well. They bought it.”

Black artists who influenced him

His African American artist heroes are Carl Owens and Barkley L. Hendricks, both of whom he knew. Owens created Anheuser-Busch’s “Great Kings of Africa” series and album covers for Motown Records. Hendricks’ works are larger-than-life portraits of African Americans. His paintings are in the collections of major museums.

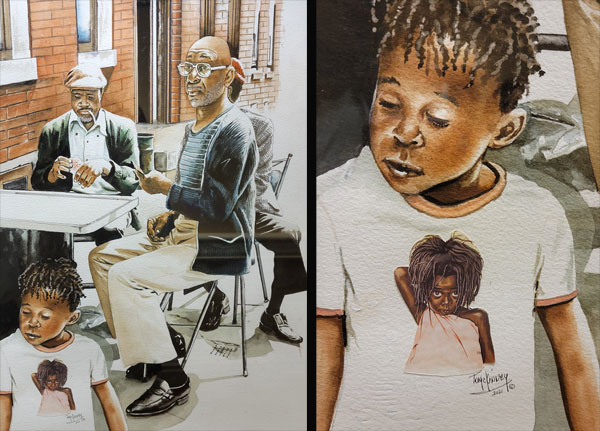

McKinney uses photographs to build his paintings: ones he has taken himself (he loves people-watching because “people fascinate me”) as well as those of a photographer named Fred F. Carter of Philadelphia and from newspaper articles. A beautiful painting of three older men in the exhibit/sale is based on a photograph by Carter. “You see the old guys playing cards? That’s me. That’s what I like to do,” McKinney says.

The influence of jazz

Jazz is a constant but invisible element in his works: “I try to capture a feeling,” McKinney says.

He is a jazz connoisseur who amassed a collection of 250 jazz albums, some of which he has sold. His father turned Little Tommy on to jazz, although his father was more into big band. After he got older, McKinney haunted the jazz clubs in Philadelphia – the Showboat, Pep’s Musical Bar and Aqua Lounge – drinking in the music but never consuming the alcohol or drugs. He has met several great jazz performers, he says.

In 1983, he created a portrait of Miles Davis for a tribute at Radio City Music Hall and met him backstage. He became friends with Grover Washington Jr. after the musician bought one of his paintings of a drummer at a Philadelphia gallery. Washington later invited him to New York for a recording session. Once, he says, he sat with Billie Holiday backstage at the Academy of Music and got her signature.

McKinney created several paintings of Davis, including one in different poses. I picked up a print of that one at an estate sale about 10 years ago. He says it was one of his most popular prints; all 1,000 sold out.

“I went to (John) Coltrane’s house in New York. I went to school with his niece. I went up there for the Randall’s Island Jazz Festival. Miles had just done the ‘Kind of Blue’ album (1959) … I say what you doing with that? She says that’s my uncle. He was playing with Miles at the time. Who walks out of the bedroom playing his horn but John Coltrane. Well, I’m done. After that, whenever Trane came to town, I would always go up to him and talk to him. I didn’t try to be buddy, buddy. I’d say, Hey and ask about her. That’s how I met a lot of musicians. When I tell people (that), they don’t believe me.”

Why he paints?

McKinney says that people always ask him these questions:

What made you paint? “And I say ‘bills.'”

What inspires you? “I say, ‘bills.'”

Not entirely, though.

“It’s just a gift,” he says. “I feel that I would commit a sin if I didn’t use it. This is what I was given. I can’t play trumpet; I wish I could play like Miles. I can’t play a saxophone; I wish I could play like Charlie Parker. I can’t, but they can’t paint like me.”

“What’s so wonderful about the creative process is you never run out of ideas,” he adds. “You’re walking down the street, and something come up. You’re sitting somewhere looking. Driving down here (for the interview at Rydal Park) I was thinking of a painting I’m getting ready to do and I was thinking of how I’m going to do it and try to find my cat.”

He has a 13-year-old cat and two male kittens who share his apartment in Warminster, PA, where the dining room serves as his studio. On this day, one of the kittens has disappeared inside his home. His cats are the models in his paintings.

Most of the humans in his paintings are Black people, because that’s who he is, McKinney says. Early on, he didn’t paint white people because he couldn’t paint them well. That changed after a friend asked him to do a portrait of a doctor at a local hospital.

“I say, Man, I can’t paint white people. He said, You ever try it? He said, They’re offering $5,000. I’m gonna try! They sent me a beautiful photograph of this doctor. The drawing wasn’t the problem. I started to paint, and I said this is not working. I got so frustrated I got up and went to the movies. My mind is still going like crazy. Your mind is a wonderful thing ’cause it goes when you’re not. I’m sitting there and something came over me. I couldn’t wait to get home. I started painting. Something told me to do this and try that and do this. All of a sudden, it just began to come out. When I finished, I say, Oh man, I didn’t know I could do this. So I called my buddy and he said, How’d you make out, and I said, You got to see this. So they bought it. They loved it.”

His childhood

He got his first serious art push from his grandmother Mabel McKinney, who was “the spirit that kept me going.” McKinney was born in Philadelphia on June 22, 1940. His parents separated, and he was raised in the home of his grandparents. Both parents remained a constant in his life: his father lived in Philadelphia and McKinney saw him every day; his mother moved to Cleveland, OH, and he visited her during the summer.

His father sketched jazz musicians he saw in Downbeat magazine, and Little Tommy drew cowboys and cartoon characters (not well, he says). His grandmother noticed that he was always drawing. One Saturday when he was 13 years old, she took him to a building in Center City Philadelphia that he did not recognize. They walked down a long hallway.

“On each side was a room and when I looked in there, there were people drawing. We finally got to the one that she wanted to go to. She walked in and this little short guy come out. He looked like Groucho Marx and he had a deep accent. His name was John Hussian. He said, Hello, Thomas. He said, So you want to be an artist. I said, I think so. My grandmother she never said a word. He said, Come on, let me show you around. So he walked me around, showed me all the people. I’m looking. I said, Man, I like this. She just smiled, and he said, Well, we can start next Saturday. You’ll come every Saturday from 9 to 12. I said, Yes sir. So she said, How you like it? I said, Grandma, thanks.”

Hussian founded the Hussian School of Art in 1946 to help GIs returning from World War II to start a career in the arts. Hussian taught him how to draw first; it would be at least two years later before he was allowed to use color, McKinney says.

He remained at Hussian for four years, receiving a certificate. He also studied for two to three years at the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts) in the 1950s.

Mabel McKinney taught him the importance of saving: When he worked as a busboy as a teenager in 1955, he handed her $15 from his $40 a week pay for savings and put another $5 in his account at a local bank. And she taught him to depend on himself: She forced him to learn to iron his own shirts.

With his salary at another job in 1960, he paid $60 for a large drawing board that he still uses (he prefers to sit as he paints). “I was really an artist then,” he says.

Joining the military

McKinney volunteered for the U.S. Army in 1963. He was at Fort Gordon, GA, when President Kennedy was assassinated (at one point, he painted a portrait of Kennedy that I picked up at auction). He was stationed later in Germany, where he painted mothers, daughters, girlfriends and dogs for fellow soldiers.

His sergeant set him up in a room at Army headquarters in the city of Budingen. “You’re good, man,” McKinney says, quoting his sergeant. “You’re going to be something someday.”

“So I started painting with poster colors and I got good at it,” he says. (Now he paints in gouache, a water-based medium, but he labels his works as watercolors for simplicity of explanation).

He left the military in 1965, then worked at Boeing, the Franklin Mint and as a freelance illustrator. Finally, he went out on his own. It wasn’t easy until he learned of the art-show circuit – malls, in particular – from white artists.

“I got on the network,” he says. “I bought equipment. I spent about $3,000 on a tent, display panels, all the stuff. I loved it because I liked the adventure of going places.”

His best work

McKinney says he has no favorites or best among his paintings. “I haven’t got there,” he says. “I never think this is my best piece. This is the best piece I did right now.”

One of his most popular prints is titled “Pretty Eyes,” which has become the one most associated with him. It shows a pretty dark-skinned Black girl with big eyes and dreads. The prints sold out as quickly as he could make them, 500 to 1,000 a month on the art-show circuit, he says. He later affixed her as a cutout on the T-shirt of the child in the painting of the card players.

“I say when I die, put ‘Pretty Eyes’ on my tombstone. It’s like everybody knows Isaac Hayes because of ‘Shaft.’ Marvin Gaye, ‘What’s Going On.’ … You’re known for one particular thing.”

Although McKinney has been painting and selling his works for decades, you won’t find any of his paintings in major museums, which is perhaps the hallmark of acceptance in the mainstream art world. Does that bother him?

“It does and it doesn’t,” he says. “It does because I figure I’m better than a lot of these people and it doesn’t because I’m still selling my art. I’ve made a living my whole life pretty much on my artwork. That says something about me and my abilities.”

We have two original pieces by Tom McKinney that we bought at an auction in North Carolina. They were framed but were in terrible condition. We thought they were prints until we had them reframed and learned they are both originals. One is a large collage of a jazz trio that we learned to be in acrylic and the other is smaller portrait of a farmer with a warm friendly demeanor that I am unsure of the medium. I love him because he reminds me of a man who was part of my childhood. We very much admire Mr. McKinney’s work and enjoy having them in our home.

I have a Tom McKinney that I purchased from Walmart as an 18yo in 1999. It’s a painting of an adolescent black boy holding a black baby in his arms and is looking down affectionately as the baby is holding his thumb. It was the first time I had seen a seemingly regular occurrence captured in paint form. It spoke to my teenage heart. I am now 44yo and still have the painting in my home. It is one of my most treasured pieces of art.

I purchased a painting directly from him at Rittenhouse Sq in the 70’s. I think it was a self portrait except the subject was playing a guitar?

Have had it on my wall for years.

Wonderful article. Thank you.

I just bought a house, and as I was unpacking my pictures, I found one I had picked up from a goodwill during one of my hunts a little over 10 years ago. It’s called “Neighbors” by Tom McKinney and decided to search it on Google and came upon this story. I’ve loved the work for years just didn’t know anything about the artist….now I know. Thank you for this beautiful story. I’ll be looking to purchase more of his work.

Hi Yolanda. It was a pleasure interviewing Tom McKinney. I’m glad you love his work.

I just bought a house, and as I was unpacking my pictures, I found one I had picked up from a goodwill during one of my hunts a little over 10 years ago. It’s called “Neighbors” by Tom McKinney and decided to search it on Google and came upon this story. I’ve loved the work for years just didn’t know anything about the artist….now I know. Thank you for this beautiful story. I’ll be looking to purchase more of his work.

I love his work. A painting stood out, so i got it. What enjoyment it is to read Mr. Mckinneys life story.

i just read all this story of TOM MCKINNEY,VERY GOOD READ SHERRY! Mr mckinney his art work I COULD SIT AND LOOK AT ALLDAY TELLS A STORY OF EACH ONE THE TRUE STORY.I FOUND THE LAZY DAYS OF SUMMER AT MY MOMS THAT HAD PASSED AWAY COUPLE YEARS AGO.YES IT CAUGHT MY EYE NOW I KNOW!

Great story, Sherry! Thank you for telling it, and for including some of Mr. McKinney’s inspiring artwork.

Thank you. He was a fun person to interview. Very witty.