The apprehension in my framer’s voice was palpable.

I had given her a painting three months before for new framing. I had called often to ask if it was finished, but each time she had an excuse for why it was not.

This time, I waited silently on the phone hoping that she would tell me that it was finally completed. Instead, she told me something I didn’t expect: The painting had been torn.

I was surprisingly calm but livid inside.

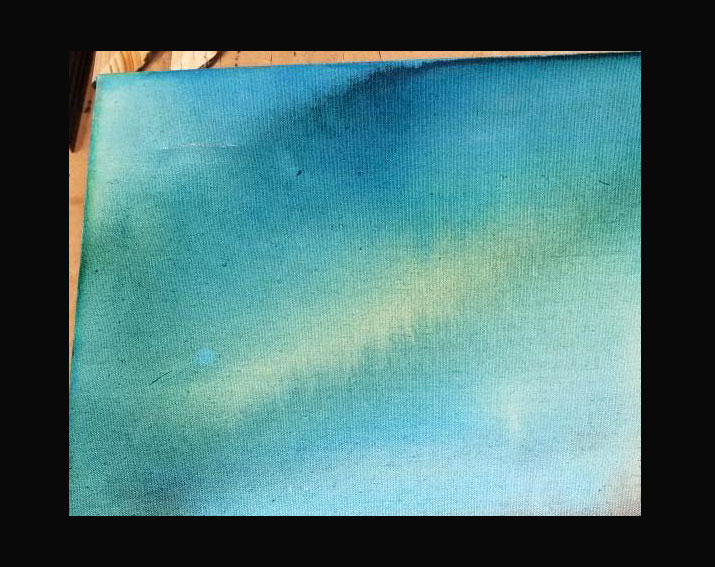

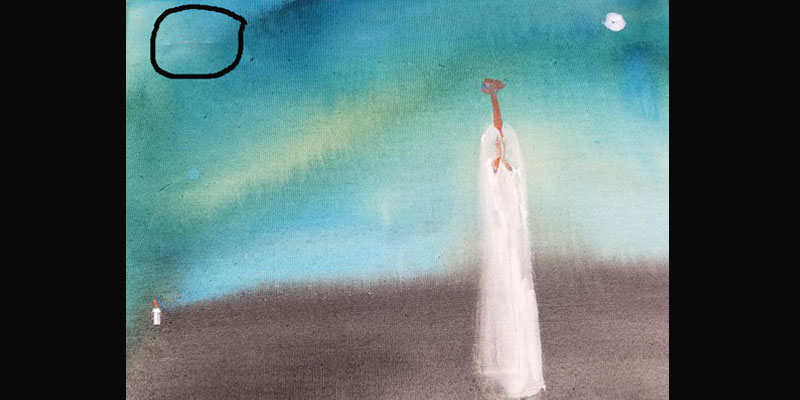

She had torn my beautiful A.C. Hollingsworth painting with the aquamarine sky and the thin brown people and the white moon. I had bought it a few years ago for more than I normally pay for artwork at auction. I was excited to purchase my first Hollingsworth, knowing that I may not get that chance again.

Now my framer of more than 20 years – who was also a friend – was telling me that she had torn it. She sent me a photo of the painting with a 2-inch tear in the upper left corner.

I listened as she told me that it had just happened. She was remorseful. I could only think that she was careless, and that made me angrier. She said she had considered having the tear repaired without telling me – which was unbelievable.

She offered to pay for the repair work. In subsequent conversations, she told me of people she knew who did conservation on the side. She was looking for someone cheap to do the repairs. That was not going to happen.

So I went searching on my own for a conservator with professional credentials. I recalled meeting conservator Mark Bockrath at an exhibit at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia some years ago and I got his card. I called him; he was busy but he recommended a conservator. He also graciously offered to vet others whom I found on my own.

One of the conservators I contacted warned me that any repair will not be perfect. So I didn’t expect the painting to look like its original self. I got costs from each of them, ranging from $3,000-$3,500 to an hourly rate of $160 (for six or eight hours for my painting) to $150-$200 to a flat $200.

An appraiser friend, Barbara Wallace, recommended two conservators whom Bockrath gave good reviews. I chose Carole Abercauph, owner of Painting Conservation Limited, who had the requisite experience, background and price.

Meeting Abercauph

Abercauph’s office was in a nondescript building on the corner of a quiet street. She met me downstairs and we went up to her studio by way of a freight elevator that was as old as the building. She operated it by pulling on a rope.

Her studio was large and messy, with paintings and easels and plants bathed in natural lighting from tall windows along a white brick wall facing the street. I loved it! I’d seen photos of artists workspaces, but this was the first one I’d actually been in. “It feels like an artist’s studio,” I said. “It is!” she replied.

Abercauph is not only a conservator but also an artist. She’s been drawing and modeling clay since she was a child. Born in Philadelphia, she was encouraged by her parents – her father Jules, a master jeweler, and mother Sadie, who ran the family business.

At age 10, she carved a mask from a round mahogany piano stool. It hangs on a wall among an eclectic gallery of artwork, a circa 19th-century gilded Italian frame that someone left behind, a repainted portrait of a gentleman and small terracotta wall hangings.

Also on the wall was a painting of an overpass/bridge on the former East River Drive in Philadelphia that she painted decades ago using egg tempera. Her base for the paint was the material in the sac around an egg yolk, she says.

Today, she mostly creates clay sculptures. Two in her studio are almost hidden on a bookshelf. Other in-progress human forms are on tables, the clay awaiting its next step.

Aubercauph has been a conservator since 1986, a year before she moved into the building.

She has an undergraduate degree in painting from the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts), which didn’t exactly prepare her for a career, she says. For several years, she was a social worker for state and city family-planning clinics.

She had thought about conservation but never acted on it. When she finally made up her mind, she was accepted into the master’s program at the Winterthur Museum/ University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation.

“Suddenly, there was the means for a path to conservation, a concrete means,” she says. “So I thought well that allows me to use my art and it also has a scientific component which I found very interesting.”

She worked for the Philadelphia Museum of Art for three years, and at small museums and historical societies, she says.

Abercauph’s work as an art conservator

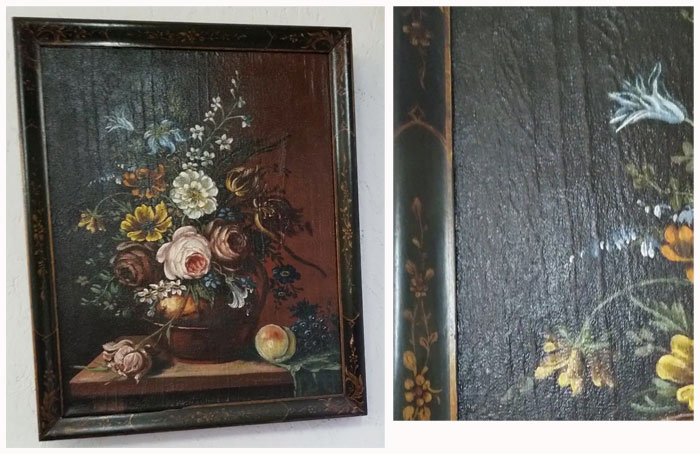

Just before I arrived at her studio, a customer had picked up a painting that Abercauph had cleaned. The owner had bought the painting at Freeman’s Auctions, the country’s oldest auction house, which is based in Philadelphia. Abercauph says she removed discolored varnish from the 1920 oil painting.

“All the time the pictures that people look at when they buy online, you’re looking at a photograph,” she says. “A photograph on a computer screen often looks a lot better than the actual painting does because the computer screen is suffused with light. So when they got the painting, it turned out to be much duller looking than what they thought it was going to be.

“Freeman suggested they bring it to me, and they did. And now they’re happy.”

Hearing that Freeman had recommended her made me feel very good about my choosing her for my Hollingsworth.

Cleaning an Andrew Jackson portrait

One of her most “wonderful” conservations was a portrait of Andrew Jackson that hangs in the Union League of Philadelphia. She discovered an inscription on the portrait and solved a mystery.

The inscription as presented in the Union League art and artifact collection:

“Painted from the Life/in rapid sittings on the 8th and 9th, Jan. 1839. [sic]/at New Orleans/by E.D. Marchant”

“That was a very tough job,” Abercauph says. “It is iffy when you have oil paint on the surface you want to remove. First of all, you don’t know what if anything is below.”

How to protect your own works

I have purchased a number of artworks from auctions that were dirty or the varnish had turned brown. “When one talks about the appearance of painting, one says, ‘Oh this is dirty and that’s clean.’ But what does dirty mean?” She explains:

Abercauph also suggests that paintings be properly fitted with a backing board to prevent dirt and other stuff from slipping behind them. She instructed me on how to dust my Hollingsworth.

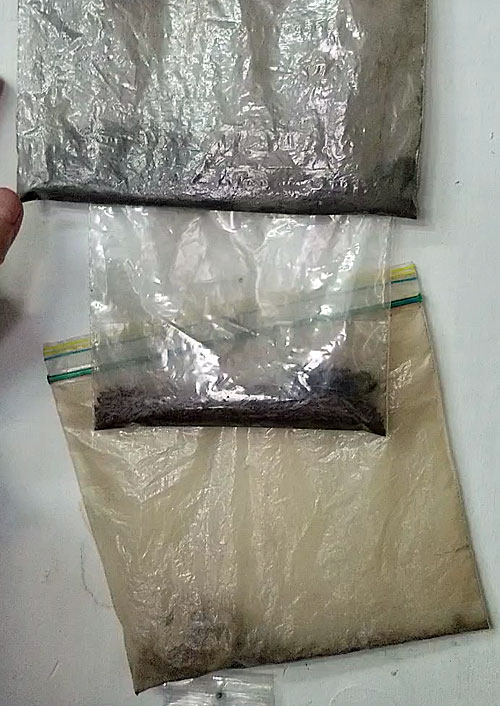

Near the gallery wall in her studio, Abercauph has attached three plastic storage bags containing some of the stuff she’s found at the bottom of the stretcher bar (the wooden frame artists use to mount their canvases) of paintings:

“Why would you know what’s going on in the back of your picture?” she says. “You wouldn’t.”

I guess it wouldn’t hurt to remove the painting from the wall once in a while if it’s hung, or handle it if it’s stored.

How can you tell if a painting is worth the cost of conservation?

Several of my paintings obviously need cleaning and repairing, but I’m not sure if they’re worth the cost. There’s no easy answer to that question, Abercauph points out. She explains with an anecdote:

The process for repairing the tear on my Hollingsworth

I was curious about how she repaired my painting. It’s not as if she could take a needle and thread and sew it back together. She outlined the process for me:

I learned from Abercauph that my painting was acrylic and not oil. I can’t tell the difference, and she noted that most people cannot.

Other works in her studio

Her workspace is filled with conservations done or waiting to be done. She points out one that was done wrong – a portrait of a gentleman that had been completely repainted by someone who knew nothing about conservation, she says. She calls it a “dead painting” because of the repainting.

“What a professional conservator (tries) to do is just retouch the damages,” she says.

She showed me an oil painting with noticeable ridge lines below the surface. The canvas was not your usual material.

“Conservation in a way it’s like archaeology,” she says. “You start with the surface and you find out what’s underneath.”

“If you look at something like that if you’re someone like me you say why are those raised lines there,” she says, “and it turns out that this little painting was painted on mattress ticking. And if you know mattress ticking has blue stripes and that blue stripe is made with a thread that is heavier than the surrounding threads and that’s what those raised lines are. They are blue threads.

“No matter what the painting for me I’m always learning things (which is why) it’s continually interesting for me.”

What she learns as she conserves a painting

Abercauph says she develops a connection with the artist whose works she conserves. She felt that with Hollingsworth, whom she researched to learn more about him.

Here’s Abercauph’s work on my painting.

Your site gets better with time! Very interesting and engaging piece. Thanks!

Valerie Harris

Thank you, Valerie. It was heartbreaking to learn of the tear but I’m happy I found Carole.

Sherry