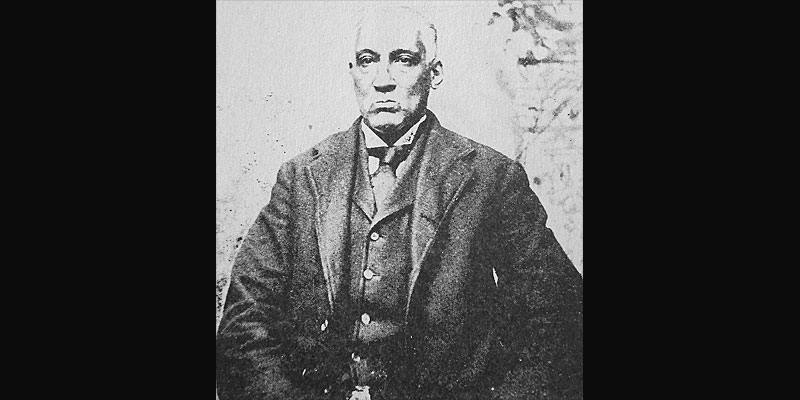

William Henry Dorsey was not only an artist but a collector.

That’s not unusual. What is unusual is that he was both at a time when Black folks were struggling to survive the dehumanization of slavery. He was building on a collection of African American art, books and memorabilia inherited from his father.

I came across Dorsey’s name some months ago while researching African American artists who went to Maine to paint. The name of Robert S. Duncanson, a landscape painter, came up in an article. Researching Duncanson, I learned of Dorsey the Black collector.

I knew I had found a kindred spirit who understood the sacredness of Black history. I was both amazed and proud that an African American had amassed an art and history collection in the 19th century. It was the same as I have been doing for dozens of years.

Duncanson is the artist whose work “Landscape with Rainbow (1859)” is on loan to President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden and hangs in the White House. The painting belongs to the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

I was familiar with Duncanson, but Dorsey was a mystery. Obviously, I was curious about who he was and how he was able to acquire his collection.

Journalist/editor James Wesley Cromwell wrote about the collection in Frederick Douglass’ New National Era newspaper in 1874. After seeing it, he was just as excited as I was about learning of it.

Cromwell and Dorsey were among a small group of African American history collectors during the 19th century. Several books from Cromwell’s own library were recently sold at Swann Auction Galleries in New York. His other books and papers are at Howard University.

On that day in September 1874, Cromwell took the stairs to the second floor of Dorsey’s home at 206 Dean Street in Philadelphia. Several rooms had been converted into a museum. The house had belonged to Dorsey’s father, Thomas, one the city’s most prominent caterers and prosperous citizens.

When Thomas died in 1875, he left behind enough capital for his family to maintain their lifestyle. William, the oldest child and only son who was born in 1837, saw himself as more an artist than a caterer. Self-taught, he was entering in an arena that American society thought Black people could not master. It took an inner creativity to produce something as wondrous as art, and in society’s view, Black folks just didn’t have it.

That’s not what Cromwell saw in the home of a man who had been a fellow student at the Institute for Colored Youth, which later became Cheyney University. Dorsey’s rooms were perhaps the first museum setting for Black history documentation.

“It was in the front room of the second story of one of those small but cosy homes of the many narrow streets of Philadelphia that we were ushered into a miniature museum and art gallery, the private collection of our old friend, Mr. William H. Dorsey, of that city,” Cromwell wrote. “Our surprise at what was in store for us was so unexpected and complete, and withal so pleasant, that we cannot resist the temptation to give the readers of the National Era an opportunity of realizing the same pleasure.

“To the lover of art, the admirer of rare curiosities, or the antiquarian, the collection of Mr. Dorsey would alike afford delight; the coins and minerals, the implements of warfare used by savage and barbarous nations, the ancient mosaics, the fine engravings, the oil and water color paintings by artists of established reputation, would repay a most critical examination.”

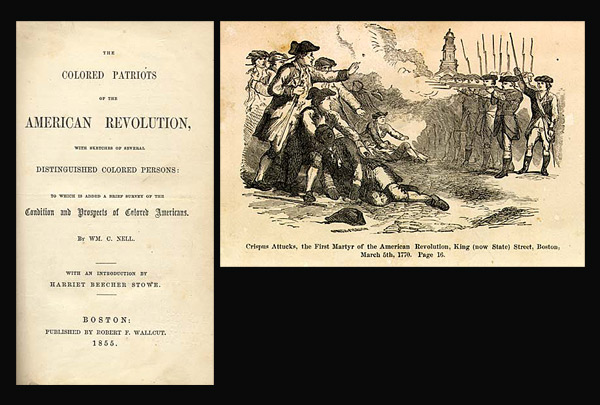

The volumes of books overwhelmed him with delight: “books and pamphlets, published by, and concerning colored men and women, – the music by colored composers – the number of steel and copper-plate engravings of eminent negroes, and photographs, autograph letters, autographs and facsimiles of men prominent in our race is very extensive, interesting, and valuable.”

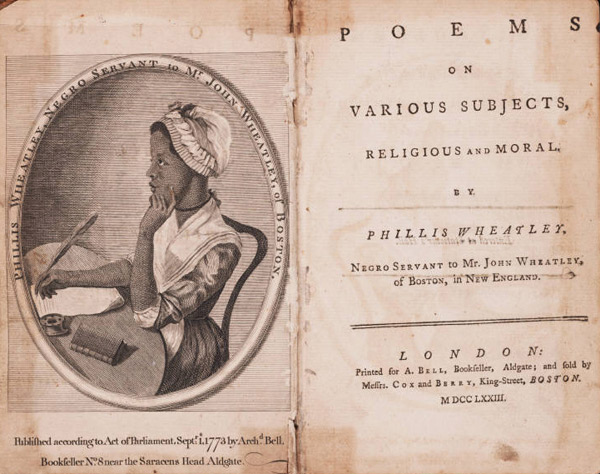

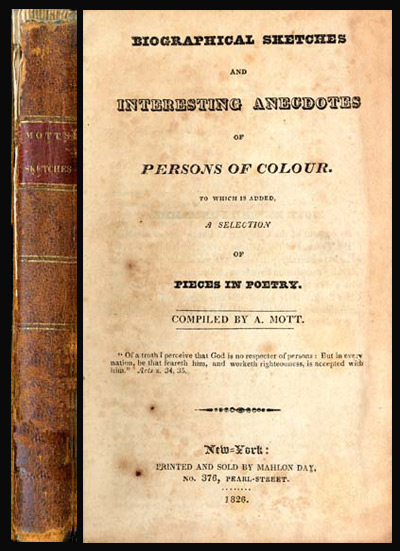

Among Dorsey’s books were:

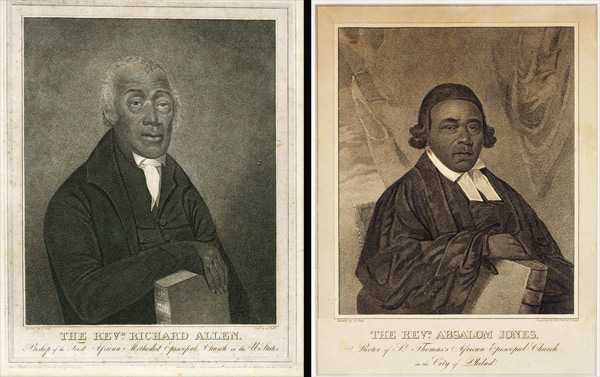

- 1801 edition of the poems of Phillis Wheatley, “embellished with a handsome copper-plate engraving, with the Revs. Absalom Jones (founder of the oldest Black church in the country) and Richard Allen (founder of the A.M.E. Church) as subscribers.”

- Henri Gregoire’s “An Enquiry Concerning the Intellectual and Moral Faculties, and Literature of Negroes (1808),” “a very rare, valuable, and remarkable work in this collection.”

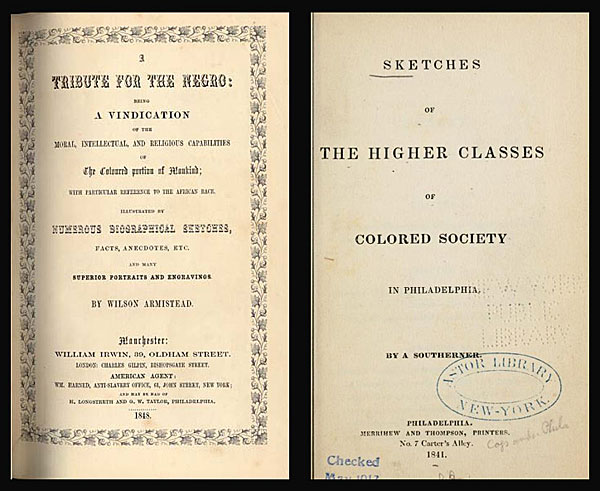

- “Sketches of the Higher Classes of Colored Society in Philadelphia (1841)” by A Southerner.

- “Tribute for the Negro,” “a work now out of print and seldom seen save in the possession of our old citizens who made pretensions to literature twenty-five years ago; or now and then at the second-hand bookstands of our metropolitan cities.”

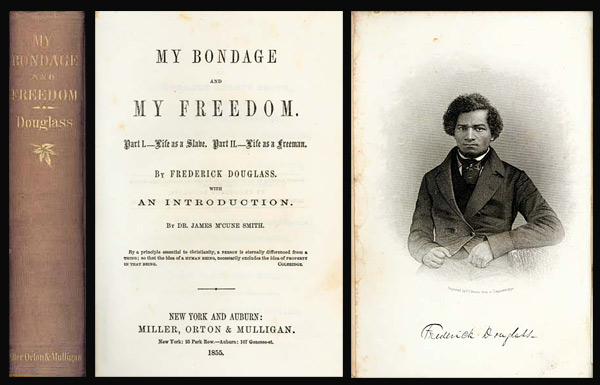

- Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” and “My Bondage and My Freedom.”

- Harriett Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

There were also letters, portraits and autographs of Douglass, musician/composer Francis “Frank” Johnson (as well as the uniform he wore in a performance before Queen Victoria), actor Ira Aldridge and abolitionist J. Sella Martin.

Then he turned to the paintings on walls where there were no bookshelves – particularly those of artist John G. Chaplin, who was working as a barber in a town outside Philadelphia. Chaplin had studied at art schools in Germany. He was said to have exhibited in the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

On a wall hung Chaplin’s “Toussaint L’Ouverture, a photograph in colors, … King Lear, in a storm scene, MacBeth, Mephistopheles in Faust, Emancipation and the Nubian are originals – the latter two, if chromoed would find a very extensive sale among that class of Americans to whom they would be specially interesting.”

There was also Duncanson’s landscape “The Evening.” A photo of a Duncanson painting titled “Evening” can be seen as a plate after page 22 here. Is it the same painting? I wondered.

A writer of an article in the Philadelphia Times who visited the museum in 1896 wrote of the artwork:

“Possibly, however, the greatest tribute to the capabilities of the negro race is displayed in Mr. Dorsey’s collection of paintings. One must confess to a feeling of surprise when it is found that a large majority of the excellent oil and watercolor paintings upon his walls are the work of negroes.”

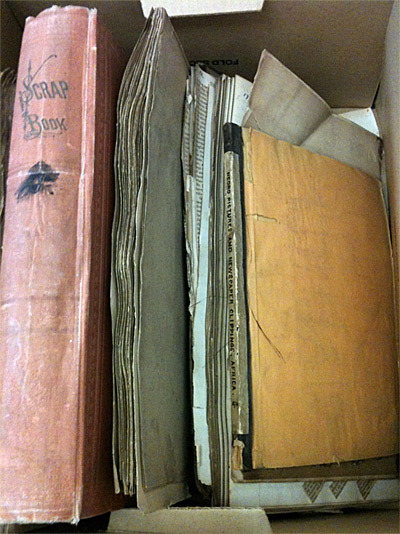

Dorsey was a prolific compiler of scrapbooks depicting Black history and culture, and Cromwell was impressed with those, too. He noted a photo of Nick Biddle, a Black man who was said to be the first person wounded in the Civil War while marching through Baltimore with a group of Union soldiers in 1861. Biddle, an orderly wearing a company uniform, and the others were attacked by Confederate sympathizers.

Another was a photo of Robert Bogle, another well-known caterer and funeral-home owner in Philadelphia who, Cromwell wrote, could “be seen officiating in his professional capacity at a funeral in the afternoon and at a party on the evening of the same day.”

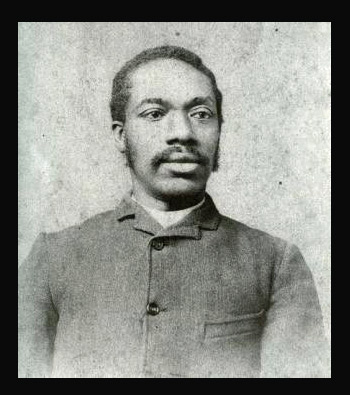

Today, Dorsey is known more for his scrapbooks. He filled hundreds of them, recording the lives of a people who were believed to have had no history beyond slavery. The books painted a picture of Black society, actors, enslaved Africans, politics, lynchings. Several were focused on Frederick Douglass. They also included ephemera on African and Native American history. W.E.B. DuBois used them to craft his book “The Philadelphia Negro,” published in 1899.

Cheyney University owns 400 of them. They are currently housed at Pennsylvania State University where they are being assessed for conservation.

In 1897, Dorsey along with collector and historian/activist Robert Adger and others founded the American Negro Historical Society whose mission was to study and preserve Black history. This was a decade before historian Carter G. Woodson organized the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History with the mission of highlighting the history through his own writings and publications.

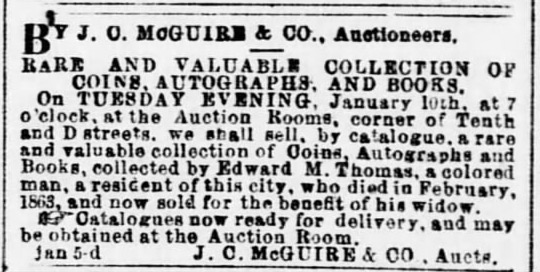

Dorsey’s contemporary, Edward M. Thomas, was also a notable collector. His home library was the subject of an article in the New York Weekly Anglo-African newspaper in 1860. The writer, a man who identified himself as Box, recounted his experience of visiting Thomas’ library.

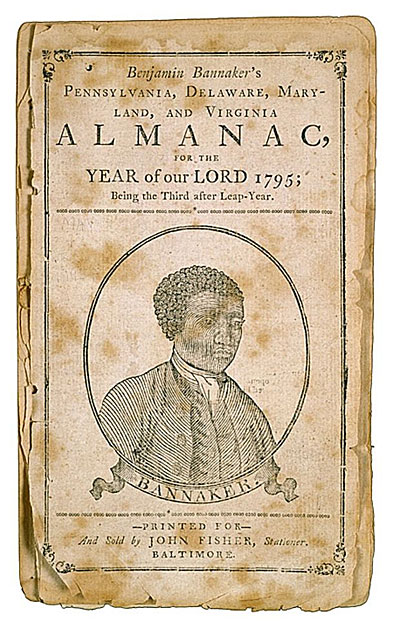

The library contained 500 to 600 ancient and modern books, 2,000 coins, and about 3,000 autographs of such people as George Washington, Lafayette who fought with Washington in the American Revolution, Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture and Black scientist Benjamin Banneker.

Box observed Chaplin’s portrait of Toussaint L’Ouverture, “the best portrait that my eyes ever beheld,” he wrote. “The life-like expression and perfectly easy and natural attitude are indeed wonderful.” He was also enamored with the artist’s portrait of Marino Faliero, the Doge of Venice (1354-55).

Chaplin was “a colored man of great artistic ability, and is acknowledged to be one of the best portrait painters in America. His great skill as an artist has been clearly set forth in the two pictures referred to, and should send a thrill of pride through the heart of every lover of the arts and sciences among our down-trodden people,” Box wrote.

Another was a life-size portrait of Thomas as well as a watercolor by Dorsey – described as “young and talented” – of a tower in ruins.

“Who would imagine in Washington that such a collection would be found to be the private property of a colored man? Many valuable collections may be found among our people, which are acquired not merely for show, but for actual study and service,” Box wrote.

Around 1861, Thomas and Dorsey, among others, began planning an exhibit of the Black artists around at the time. Thomas died in 1863 before it could be implemented.

Thomas’ coins, books and autographs were advertised in a Washington newspaper in 1865 to be sold at auction with proceeds to go to his wife. At some point, his paintings were apparently sold, including Thomas’ bust by white sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward and the portrait of L’Ouverture that were in Dorsey’s collection.

Black artists were not taken seriously by the mainstream art world or society in general. In 1877, Cromwell asked Dorsey to respond to a letter-writer in the People’s Advocate newspaper lamenting the lack of portraits of Black people. Cromwell was the founder of the Washington-area newspaper.

Dorsey pointed to his friend Robert Douglass Jr.’s portraits of Haitian generals and Liberian statesmen, and Chaplin’s “Toussaint L’Ouverture” and “The Death of Hannibal” that Dorsey’s mother owned.

In addition to Duncanson, Douglass and Dorsey, others included David Bustill Bowser, Patrick Henry Reason, Edward Mitchell Bannister and Edmonia Lewis, whose marble sculpture “The Death of Cleopatra” won high praise at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876.

Dorsey laid out the barriers faced by Black artists: Galleries would not accept them, exhibitions were only now starting to open to them and “you need money to be an artist, and prejudice kept them out.”

Bannister’s experience with a centennial committee bore this out. His “Under the Oaks” won a first-prize medal for painting. When he learned of the win, he went to the committee room to verify it.

“I endeavored to gain the attention of the official in charge. He was very insolent. Without raising his eyes, he demanded in the most exasperating tone of voice, ‘Well, what do you want here anyway? Speak lively.’ ‘I want to enquire concerning 54. It is a prize winner?’ ‘What’s it to you,’ said he. In an instant my blood was up: the looks that passed between him and the others in the room was unmistakable. I was not an artist to them, simply an inquisitive colored man; controlling myself, I said deliberately, ‘I am interested in the report that Under the Oaks has received a prize; I painted the picture.’ An explosion could not have made a more marked impression. Without hesitation he apologized and soon everyone in the room was bowing and scraping to me.”

The judge of the competition tried to rescind the award but was thwarted when other artists in the exhibition strongly objected.

The painting has been lost, but it was said to likely resemble his “Oak Trees (1876)” in style. That painting is in the Smithsonian.

The Philadelphia Times newspaper published an article naming some of the most well-known Black artists in 1890: Bowser, Douglass, Dorsey, Henry Ossawa Tanner and Alfred B. Stidum, known for his crayon portraits. Tanner was getting his footing as a photographer and painter. In 1891, he moved to France to study and remained in a land where he was more readily accepted.

There were African American artists before them, the most notable was Joshua Johnson (or Johnston). He was perhaps the first documented professional Black painter – as described by the Smithsonian.

A watercolorist, Dorsey was represented in some local shows. In 1880, he exhibited with several other Black artists at the Working Men’s Club of Philadelphia. They included Tanner, Duncanson, Bannister, Douglass, Bowser and Stidum.

While Dorsey was filling his museum, he worked as a civil servant under two mayors, as a personal messenger in the office of one and a turnkey of another. As a turnkey, he apparently was a jailer who kept the keys and locked the cells of prisoners in a City Hall jail.

Dorsey died in 1923. His scrapbooks are presumably all that’s left of his collection in his name.

He and Thomas were their century’s version of Arthur Schomburg and Charles Blockson, who in the 20th century compiled their own collections. The former had no repository for theirs, so their collections disappeared.

Schomburg’s is housed in a New York Public Library research library in Harlem that bears his name. Blockson’s is in a center at Temple University in Philadelphia that is named after him.