First, I saw a dark wooden sign with large white letters that told me I was at the right place: The historic site of Dr. James Still, known as the “Black Doctor of the Pines.” Nearby was a building covered in plastic as if it was being restored. Two workmen stood near it, talking.

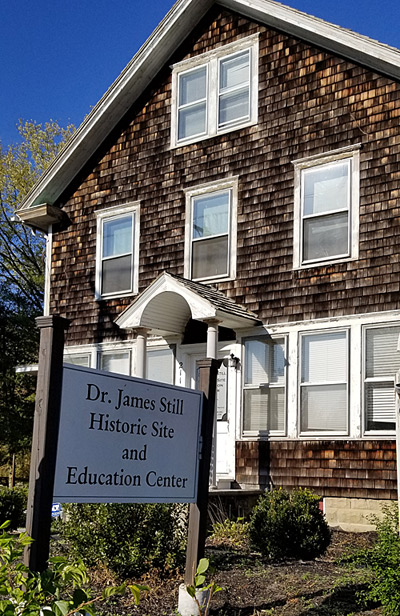

I drove past the structure to a cute brown shingled house with barns to the side and back of it. In front was a sign declaring it as the education center for the Dr. James Still Historic Site.

The site was one that you won’t likely find in an American history book. The plastic-covered building was the office of Still, a self-educated African American herbalist and homeopathic doctor who lived during the 19th century. His life and history are amazing because he was able to rise above an impoverished childhood and racist limitations to become one of the richest men in Burlington County, NJ.

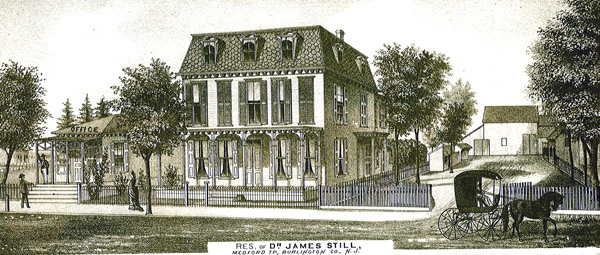

Starting in the 1840s, Still made his money by developing medicine from herbs and plants, which he sold to treat illnesses. He built a mansion and medical office on Church Road in Medford, NJ, and owned property throughout the county. His house was torn down in the 1930s and the office remained for years as a private home.

Around 2006, the office was purchased by the state of New Jersey, along with the shingled house and barn that were part of the old Bunning Farm next door. The plan was to renovate the office, but that has not yet happened. A group of volunteers cleaned up the farm property, and the farmhouse was made into an educational center operated by the Medford Historical Society. It offers workshops, seminars and other events.

Still dispensed his medicines in New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, a place I was always curious to visit. It would come up often in news reports when a fire raged uncontrollably through the woodlands. I learned about Still while researching what I’d find if I ever visited.

Last week, I took a trip to the Pinelands on a beautiful day to bask in the changing colors of autumn. I had stopped off at the historic Batsto Village on Route 542 when I remembered the story of the “Black Doctor of the Pines.” I knew I had to find the spot where Still had started out with little and ended up with much.

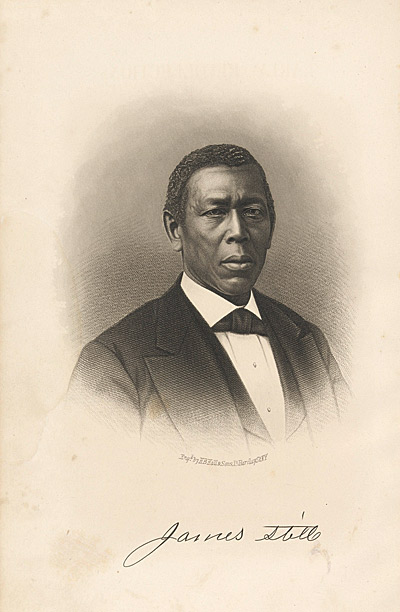

During the period James Still was born, he wasn’t expected to exceed at anything. His parents were enslaved Africans who lived on separate plantations in Maryland. His father was able to buy his freedom in 1798; his mother was not. With the help of abolitionists, his father made his way to New Jersey and worked to free his family. His mother tried to escape slavery once with her children and then again with her two daughters. She succeeded the second time but had to leave two sons behind.

That was “a great grief,” Still wrote in his 1877 autobiography titled “Early Recollections and Life of Dr. James Still.” The book details his personal life as well as stories of the patients he helped, the doctors who snubbed him, and his land purchases and deals. It was last reprinted in 2015.

Still was born in 1812 in Indian Mills, Burlington County. His formal education was limited, and he attended school for only about three months. Many times, the family had no food or clothing, he wrote in his autobiography.

The idea of helping sick people took hold of him when a doctor came to his home while vaccinating children in the area. “It took deep root in me, so deep that all the drought of poverty or lack of education could not destroy the desire,” he wrote. As an adult, he worked a number of menial jobs until he began distilling oils from herbs and plants that he sold. The idea of medicine was still burrowed in his brain.

He read books on botany and other medical subjects. Medical school was out of reach, so he taught himself. One of his first patients was a man who traded sassafras growing near his fence for some of Still’s home remedies, according to his autobiography. The man got better, as did many of his other patients, he noted. He was selling his herbal products at a time when ads touting cures and wonder drugs flooded the pages of newspapers.

“It did not occur to me at this time, however, that I was practising medicine …,” he wrote. “The doctors laughed at me behind my back at seeing my white-top wagon and myself going through the country healing the sick, and I laughed myself sometimes, but I could do no better.”

He was not making much money, though, because he wasn’t collecting payment on the spot. He changed his collection process, and his finances improved. He did so well that he eventually built a large home for his family and an office for his business.

“No man has taught me,” he wrote. “I can only account for success by endeavoring always to be honest in all things, – in medical treatment and in business operations, – and in a reliance upon that Divine Being who cares for the sparrow in its flight, and who uses the weak things of the world to confound the mighty. These principles I have endeavored to instil in the minds of my sons.”

His son James Thomas was one of the first African Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School in 1871. His son Joseph became an herbalist.

Still was not the only renowned person in his family. His brother William was an abolitionist in Philadelphia and wrote his own book about the Underground Railroad. His brother Peter, whom his mother had to leave behind in Maryland, eventually was reunited with the family and spent his time trying to free the wife and children he had to leave behind.

“He served in slavery forty-five years, and by saving and industry was enabled to buy his freedom from his master whilst living in Alabama …,” wrote Still. “He came to Philadelphia … and found his own brother clerk in the Anti-Slavery office there, and from him learned the whereabouts of his mother and brothers.”

Still died in 1882 at age 70. He was known as the “black cancer doctor” across the country, according to a blurb in several newspapers announcing his death.

Wow! I had never heard of him. You find such wonderful stories to enlighten us.