An African American baker named Cyrus Bustill baked bread for George Washington’s troops during the Revolutionary War. That’s what the documents showed, but family historian Joyce Mosley wanted more verification.

So she decided to join the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), the group of female war descendants that in 1939 had refused to allow the renowned Marian Anderson to perform in its Constitution Hall. When most Black women think of joining an organization, the DAR isn’t the first to come to mind. Many of us can recall the iconic photo of Anderson on that April day bundled in a fur coat at the Lincoln Memorial – forced out into the cold because her skin was Black.

Mosley acknowledges the snub, but the DAR had something she wanted: the authority and expertise to ensure that her great-great-great-great-great grandfather would get the recognition that was due him.

“I wanted to authenticate … that Cyrus Bustill baked bread for George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge and that he actually drove a wagon out there,” said Mosley, who has been researching her family history for the last 25 years. “I wanted a source to agree that it was true information. So, they were kind of my confirmation that the history that I had and I documented was all correct.”

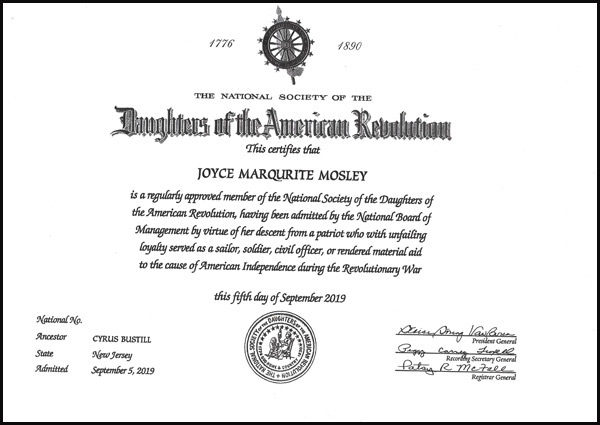

The DAR did not initially accept Mosley’s documents because they were not official government records. Over several years, members of the organization researched and authenticated that Bustill did indeed provide bread for the Continental Army, but it could find no records that the bread was delivered to Valley Forge. After three years, Mosley said, she became a member of the DAR in 2019.

How Bustill’s contribution was documented

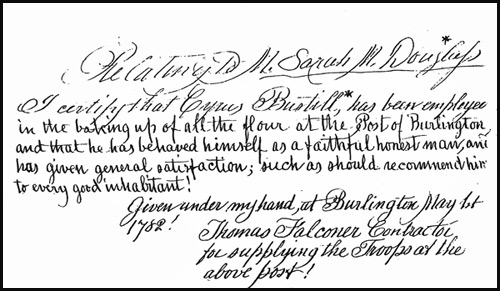

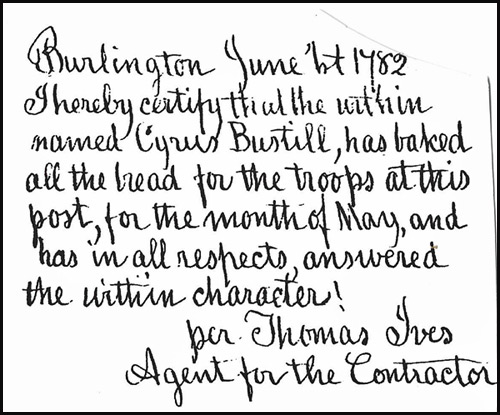

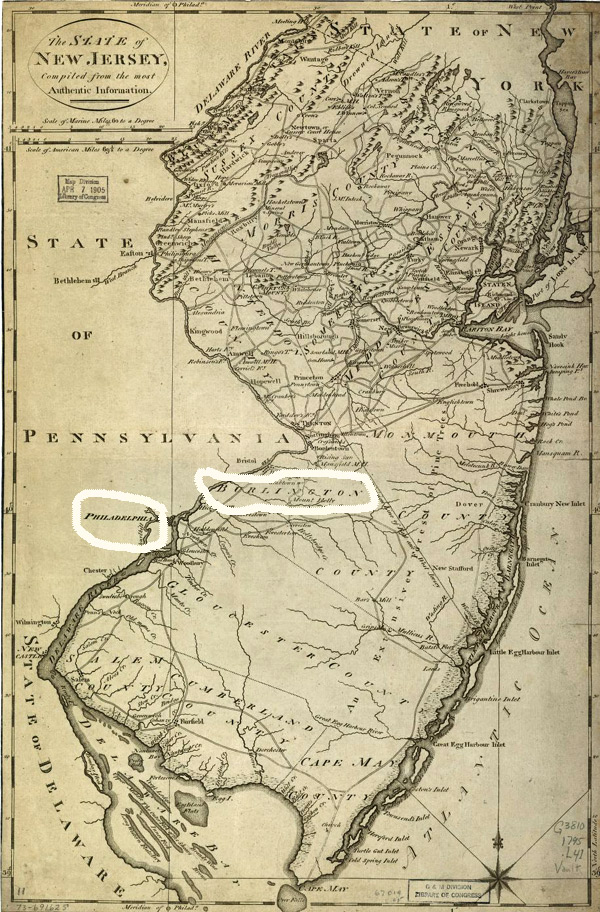

Mosley has handwritten documents signed in 1782 by two contractors who were in charge of providing supplies for the Continental Army. Thomas Falconer wrote that Bustill baked bread for troops at the port of Burlington, NJ. A second document signed by Thomas Ives attested to the same. A written line at the top stated that Sarah Mapps Douglass, Bustill’s granddaughter, was involved in some way in the documentation, presumably during the 19th century since she was born in 1806.

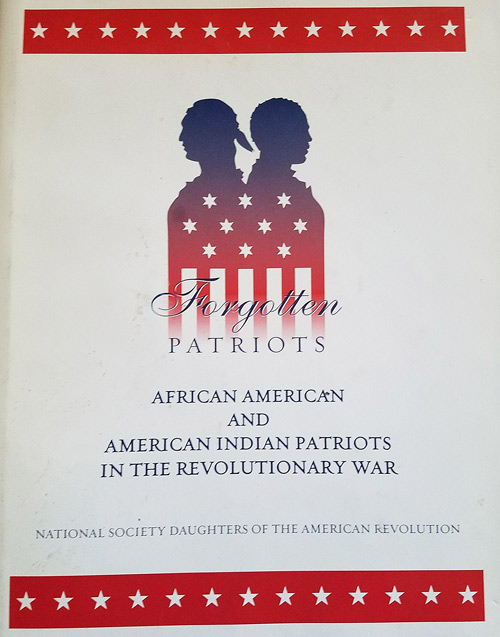

Another sign of proof, Mosley said, came from the DAR itself: Bustill was cited in the DAR’s 2008 publication “Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War.”

Her application was eventually assigned to Yvonne Liser, chairman of the DAR national Membership Committee and a member of a task force that helps locate documents and solve documentation issues for potential members.

Liser said the group’s genealogists could not accept the papers that Mosley offered. And Bustill being mentioned in the ‘Forgotten Patriots’ publication was not proof, she said, because those listed were not subject to the rigorous research the DAR requires for membership.

“The documents used to prove Cyrus Bustill’s service were 1) not original … and 2) not a government produced record,” Liser said in an email. “The DAR standards generally require primary sources, which the letters are not. The documents used to prove Cyrus provided bread/flour to the troops were letters from men that were agents for purchasing items for the troops and seem to be letters of recommendation from men who had done business with Cyrus.

“It just so happens the letters mention his service. These letters were transcribed by Cyrus’ granddaughter Sarah M. Douglass (known transcription because she wrote that at the top of the transcription). The reason we were able to get DAR to approve it is because I proved the providence of the letters through newspaper articles that included interviews with the granddaughter in addition to his own words spoken in a speech transcribed at the time he spoke it. We also proved the occupations of the persons who signed the letters.”

Liser and DAR members consulted museums, universities and libraries, and state archives in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, she said. “I ordered every microfilm for NJ state colonial war records, but he was not mentioned,” said Liser, a genealogist who is a member of the District of Columbia Chapter. “We checked all over for state records proving he provided bread/flour, but none were found. The transcribed letters were the proof needed to verify service, so I stuck to proving providence on those.”

“The letters stated he provided flour and bread to the troops at the post of Burlington, NJ,” Liser added. “We did not attempt to prove his service at Valley Forge, just verify the service provided in the letters. Unfortunately, we did not find proof of service beyond what was in the letters.”

Mosley says Bustill’s contribution of bread to the Continental Army extended beyond Burlington.

“The flour at the Port of Burlington was owned by the Continental Army,” she said in explaining the Valley Forge connection. “Both Falconer and Ives were contractors for the quartermaster department of the army. This department was responsible for acquiring supplies and hiring vendors to bake bread assigned to feeding the troops at Valley Forge.”

Becoming a member of the DAR

Mosley is a member of the Flag House Chapter, where she is the only African American among about 20 members, she said. The DAR has more than 186,000 members, said Liser, adding that the organization keeps no records on how many are African American. The group admitted its first black member in 1977 and named the first black woman to its national board last year.

Mosley, who’s part of an unofficial group inside DAR that calls itself “Daughters of Color,” noted about 60 women on a Zoom conference of that group this year. The stories of how some women of color became DAR members are featured an un-affiliated podcast titled “Daughter Dialogues.”

To join the DAR, a woman must prove that her ancestor contributed to the war in the period from 1775 to 1783. Among soldiers, an estimated 5,000 to 8,000 African Americans served in the Continental Army (20,000 fought with the British). On its website, the DAR has a list of ways a person could have served. This one seemed a likely category for Bustill:

“Those who rendered material aid and supported the cause of American Independence by furnishing supplies, with or without remuneration, loaning money and/or providing munitions. … The National Society reserves the right to determine the acceptability of all service and proof thereof.”

Sara Sukol, the DAR’s director of genealogy, says the organization accepts various forms of documentation for verification. “DAR never ‘pre-judges’ any documentation,” Sukol said in an email. “This, in effect, means we simply don’t say we would accept a pension, military record or ANY record for a patriot without reviewing it in context with an application. … We have accepted (and continue to do so) many different records to document military service.

“Yes, normally it’s a militia list, payment voucher or pension record in the case of military service, along with town and county records in the case of patriotic and civil service. However, we examine all documentation on a case-by-case basis and in conjunction with and in context of the entire application.”

Is it tougher for many African American women given their ancestors’ status in 18th– century America?

“Women joining with a free Black patriot generally have it easier than a woman joining with a lineage that includes a white patriot and enslaved (descendant),” said Liser. “‘Free Negroes’ had records such as wills, probate, pension, registrations of freedom, business records, etc., just like white men. Slaves were property with no records for the most part. Women who have joined that are descended from an enslaved person and a white person descended from a white patriot have a much more difficult time. There has to be some proof of parentage, which can be difficult. However, we are able to submit lineage analysis if we cannot find direct proof of parentage and to prove other things.

“For example, one member’s enslaved ancestor and her children were freed in the will of her enslaver, who he referred to her as his ‘dearest gal.’ The staff accepted that as proof of relationship.”

Many of the Black DAR members she has encountered, she said, are linked to a white male. Liser comes from a lineage of free Blacks from Virginia on both sides of her family. A Black man on her mother’s side was a soldier in the Continental Army. On her father’s side, a Black man paid a tax to support the war.

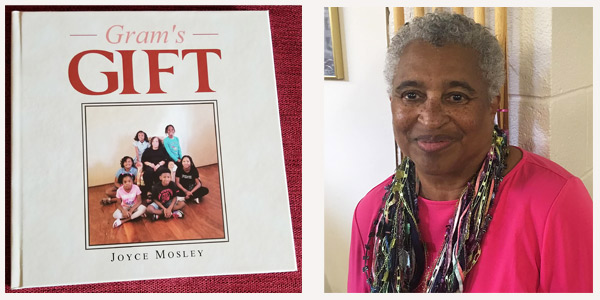

Joyce Mosley has been researching the history of Cyrus Bustill’s family for 25 years. A fifth-generation granddaughter, she has written a children’s book about his legacy.

The Bustills were a keeper of records

The Bustill family has long believed in recording its history. That has made Mosley’s research easier than it is for most African Americans. Her family documents are in archives at several historical societies and universities, including Howard University in Washington. A newspaper article from 1879 mentioned Sarah Mapps Douglass, who “has her genealogy written out for several generations back.”

“We’ve always had a written history,” said Mosley, who is related through Bustill’s daughter Leah. “We’ve had family reunions since 1902. Oral history was passed down from generation to generation, and my grandmother asked me to document it … because some of it was getting lost as it passed down the generations.”

Not only has she written down the history, Mosley has committed it to memory. She sharply and without hesitation cites names and dates as if she’s reading them on paper. Mosley has written a children’s book titled “Gram’s Gift” about a grandmother telling her grandchildren the story of Bustill and his lineage.

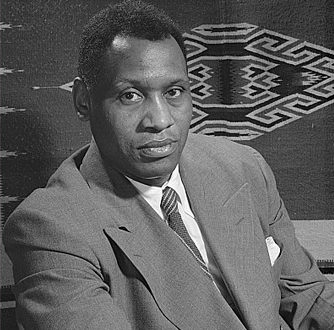

Cyrus Bustill was the patriarch of a long line of intellectuals, abolitionists and social activists, including singer/actor/activist Paul Robeson (great, great grandson); suffragettes Grace Bustill Douglass (daughter) and her daughter Sara Mapps Douglass; painter Robert Douglass Jr. (grandson) and David Bustill Bowser (grandson), an artist who made flags for the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War.

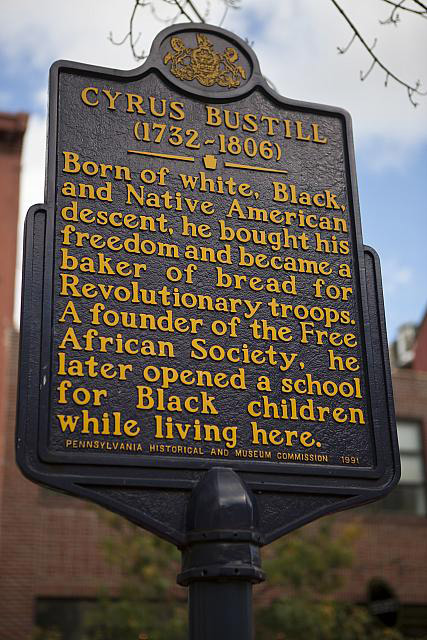

He was born an enslaved African in Burlington, NJ, in 1732 and appears to have been accepted to some degree into his white father’s Quaker family. Although Quakers had renounced slavery, Bustill’s father was among those who retained them. After the father died, 10-year-old Bustill was sold. He eventually worked out a deal with another Quaker – a baker – to purchase him, allow him to work much like an indentured servant and free him in seven years.

During his servitude, Bustill learned to be a baker. He was freed in 1769 at age 37, he later said in a speech, and opened his own bakery in Burlington. It was during the subsequent years that he baked bread for the Continental Army. Washington was at Valley Forge from December 1777 to June 1778.

“He learned to read and write when he was in his 30s, and he paid a white boy to teach him to read and write while the bread was baking,” said Mosley. “And he would teach himself at night with a candle in the bakery shop.”

Along the way, Bustill became a Quaker and embraced its teachings and traditions. He took the idea of nonviolence and forgiveness to heart. In 1787, he gave a speech in Philadelphia to enslaved Africans that seemed to advise acquiescence and patience with rewards waiting for them after they died. The family attended the Arch Street Friends Meetinghouse.

After the war, Bustill moved his family to Philadelphia and opened a bakery. An historical marker was erected in his honor at 210 Arch Street in 1992. His daughter Grace operated a millinery shop next door to the bakery.

He contributed money to help start the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and was a member of the Free African Society, a mutual-aid organization that assisted Blacks and enslaved Africans seeking freedom. He was involved in the Underground Railroad. He organized Blacks to bury the dead and assist the sick during the yellow-fever epidemic in 1793. He opened a school for Black children in his home (his granddaughter Sarah would eventually do the same).

Bustill died in 1806. Mosley has documented his grave in a family plot that was paved over on Limekiln Pike just outside Philadelphia. The site is located near a home whose original structure was built by a member of the family.

Cyrus Bustill’s story is among those that fill in the blanks of American history, and that partly drove Mosley to stick with her campaign to join the DAR. “I was going to do this,” she said. “Tell me I can’t do something, then watch me do it. It was just my tenacity.”

So why would Mosley want to be a member? There must be other ways to authenticate Bustill’s role.

“I wanted to be inside to change things, but I also wanted recognition of Cyrus Bustill,” said Mosley. “So many of our heroes get no recognition at all, get written out of history. So if I didn’t persevere and prove that he was worthy of membership, then I feel like I missed that opportunity to push African American history forward.”

What a wonderful and uplifting story. Thank you for sharing this.

Thank you Sherry for telling my family’s story.

Gram’s Gift is available at:

authorhouse.com

amazon.com

Joyce,

I am so proud of you and envious of your tenacity and perseverance. We always say, “Mimi would be so proud of you for keeping our history alive”, but I’m sure Grandpop would be too.

Thank you. Love you much.