As the flu pandemic raged, a desperate call went out in Richmond, VA, in the fall of 1918.

White doctors needed volunteers, particularly nurses, to help care for the endless flow of sick patients at John Marshall High School, which had been converted into an emergency hospital. The pandemic had forced them to put aside their prejudices; they were accepting volunteers of all types, including African Americans.

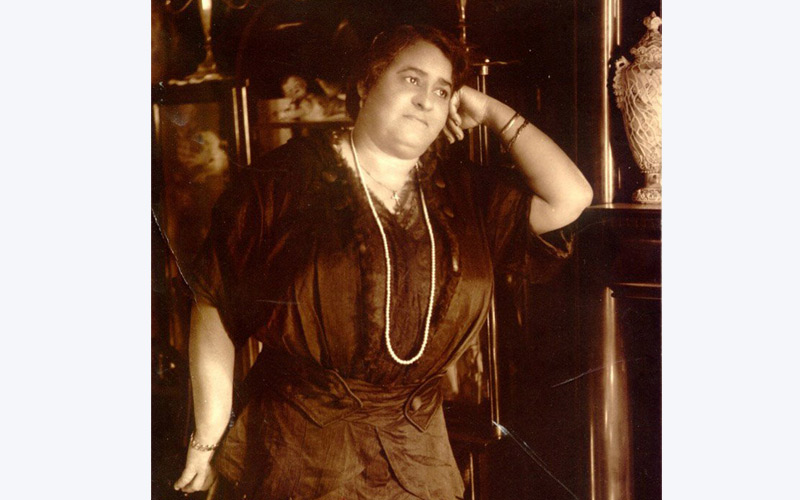

Maggie L. Walker, a member of the American Red Cross and one of the city’s most influential African Americans, and several other black women arrived at the school to offer their services.

What they found was disturbing: Black flu patients were housed in the basement and likely were not getting care equal to that of white patients on the main floor.

This was a sign of the times in a segregated society, and Walker was sure to know it. But she also understood that it didn’t have to be that way. She knew it from what she had accomplished through her own grit and smarts. Through the mutual-aid organization that she headed, she had opened a savings bank and an emporium next door to white shops downtown and a newspaper. She had showed African Americans what they could achieve on their own.

So, Walker and a group of other black residents persuaded the governor to open the black Baker Elementary School – which like Marshall had been closed because of the pandemic – to use as a hospital for black patients. The governor agreed.

Dr. William H. Hughes and 21 other black doctors pulled together a staff, and he was chosen as medical chief. Along with other volunteers, they were said to have seen 180 patients by the time the school reopened for students a month later.

Black medical professionals were combining their skills and expertise in aiding sick people in their neighborhoods where medical care and facilities were separate and unequal. Their counterparts in other cities were doing the same.

In Philadelphia, Dr. Nathan Francis Mossell, the medical director and co-founder of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital, set up an emergency location at a catholic school after its 75 beds quickly filled up. In Baltimore, the 40 beds in the sole black hospital, Provident, had to turn people away (across the country, many people, black and white, were treated – and died – at home under the care of visiting nurses).

The need for nurses was so great that the Army abolished its rule against using black nurses and solicited them. They cared for both black and white soldiers, but lived in segregated barracks. Many of the white doctors and nurses had been sent overseas to tend to U.S. soldiers.

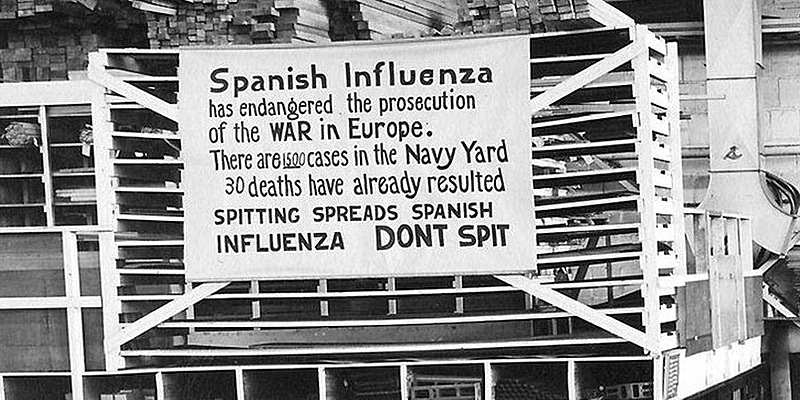

Although there was the notion among blacks that the virus was bypassing them, it was equally virulent among all groups. The virus killed about 675,000 people in the United States and up to 50 million worldwide.

It first spread in this country among U.S. soldiers in tight quarters on military bases where they were training for war. They, in turn, carried it with them on ships to Europe. The virus shot through the United States in three stages: early 1918, fall 1918 and early 1919, when it hit the hardest. It seemed to have a lighter impact in cities where people seriously engaged in social distancing.

Philadelphia has a dark spot on its history because of one foolhardy decision by its public health director. He minimized the severity of the outbreak, giving the go-ahead for a Liberty Bond Parade in support of World War I in September 1918 that drew hundreds of thousands of people. The throng watched soldiers, marching bands, Boy Scouts, military equipment and others along a route in downtown Philadelphia.

Three days later, all of the city’s hospitals were full and 2,600 people had died. And it got worse.

Given her background and influence, it wasn’t surprising that Walker would volunteer and then feel comfortable asking the governor for hospital space for her people. For decades, she’d been looking out for them. She kept their money safe in the black St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank, where she president, and she was a tireless advocate for the Independent Order of St. Luke, a self-help mutual-aid society that she pulled out of a financial mire when the previous director couldn’t.

The bank was part of St. Luke’s conglomerate of businesses that included the emporium, newspaper and print shop. The bank employed a large number of black females in white-collar jobs that were denied them in white businesses.

Walker was an ardent speaker who preached self-determination in the context of religion. She traveled far and near to build up St. Luke’s membership and its assets.

She was also a civil rights activist long before the term was commonly ascribed to those who fought for black people. She and her teacher-college classmates agitated to hold their graduation ceremony at the City Auditorium in Richmond with white students. They were permitted to do so but were segregated from the whites. She also protested segregated streetcars in the city.

Today, a memorial statue of Walker stands in downtown Richmond, and her house is a national historic site operated by the National Park Service.

Maggie Walker used the skills she had developed in building coalitions in the local, regional and national African American community to improve conditions for victims of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Mrs. Walker and Virginia’s First Lady Marguerite Davis worked together to provide better care for patients at the converted hospital established at John Marshall High School. They recruited individuals across all walks of life: nuns and other white and black volunteers to nurse patients; Boy Scouts to serve as stretcher bearers; and the local Young Man’s Hebrew Association to man a convalescent center for recovering patients. Truly, Mrs. Walker was a remarkable and capable woman.

Sherry, Excellent article. Would it be possible to purchase a copy of this article? Jantra

Glad you enjoyed the post, Jantra. Sorry, I don’t have a copy of the post but you can link to it. Thanks, Sherry.