It took a minute for the revelation to sink in.

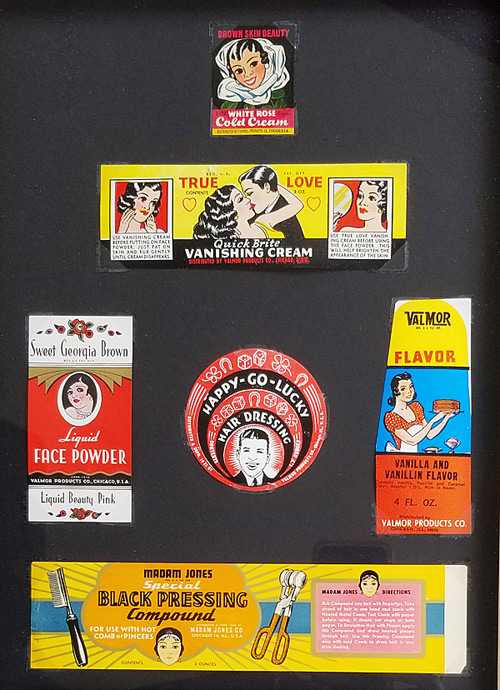

There in front of me were images of some of the hair-care product labels I had picked up years ago at a collectibles’ show. They were color illustrations of African American women whose tight African curls had been straightened into sleek shiny waves and whose dark African skin had been lightened to a rosy pink.

The labels had always been anonymous to me. I bought them because of their artistic quality, although I knew they were mass-produced by some company to show black men and women how to turn their own natural look into mainstream’s version of beauty in the early 20th century. Even before I bought them, I had seen ads for the beauty and hair creams in black publications.

I was excited to discover that the labels were created by an African American graphic artist named Charles Clarence Dawson, who was quite well known for his illustrations. Based in Chicago, Dawson worked for Valmor Products, a white-owned company that targeted black men and women women for its hair and beauty products.

Owner Morton Neumann never allowed Dawson – or Jay Jackson, another black graphic artist who came after him – to sign any of their labels. (Dawson did sign some of his ad work for other clients.)

Dawson was one of Chicago’s most renowned graphic artists. He worked as a freelancer for both black and white clients during the 1920s and 1930s, creating posters and advertisements aimed at black consumers. He and the other Chicago artists who helped shape historian Alain Locke’s “New Negro” movement were overshadowed by the iconic Harlem Renaissance in New York .

Dawson was born in 1889 in Brunswick, GA, and drew pictures of rural workers as a child. He attended Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and after graduating, landed in New York where he became the first black student to attend the Art Students League. He endured the discrimination there as long as he could. After saving enough money by working in a Pullman buffet car, he made his way in 1912 to the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the few art schools open to African American students.

His institute classmates included artist Archibald J. Motley Jr., who would eventually outshine him as a painter. He was among the students who founded the Arts and Letters Society, the first black artists group in Chicago whose focus was to get recognition for black artists. Dawson served in the army during World War I and was assigned to an all-black regiment known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

He was said to have seen combat in France. A U.S. general “loaned” some members of Dawson’s division to the French military to fight under its flag.

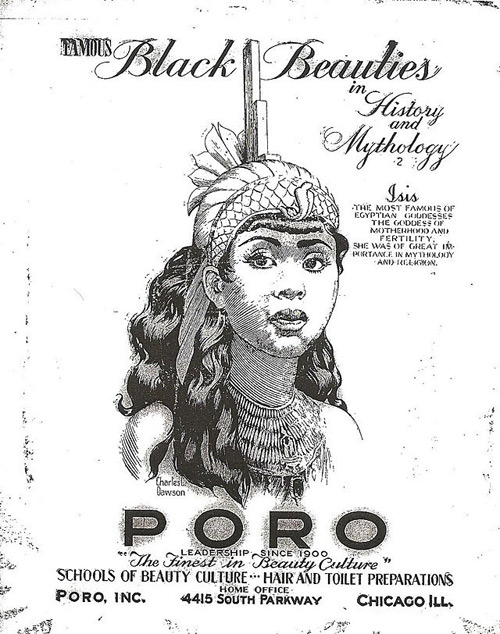

Back in Chicago after the war, Dawson worked as a salesman, but then turned to freelancing. Among his clients were black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux; Anthony Overton, who among other things owned a beauty company whose ads also featured skin-lightening and hair-straightening products, and Annie Turbo Malone, who founded a cosmetology school called Poro College in 1917.

A philanthropist who made her own products, Malone built a black hair-care empire before the better-known Madame C.J. Walker. In fact, Walker was one of her sales agents. At the time, beauty and hair-care items were sold door to door by agents or through the mail.

In 1924, Dawson and fellow Art Institute student William McKnight Farrow helped form the Chicago Art League, a club that held exhibits for African American artists who were shunned by white museums and galleries. Three years later, the club helped organize “Negro in Art Week” sponsored by the Chicago Woman’s Club at the Art Institute, according to “A History of African American Artists” by Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson.

Dawson created the cover design for the ‘Negro in Art Week” exhibition catalog, which included three of his own works. In 1933, he was called on to paint the mural “Negro Migration: The Exodus” for the National Urban League’s exhibit at the “Century of Progress” World’s Fair in Chicago (also known as the Chicago Exposition).

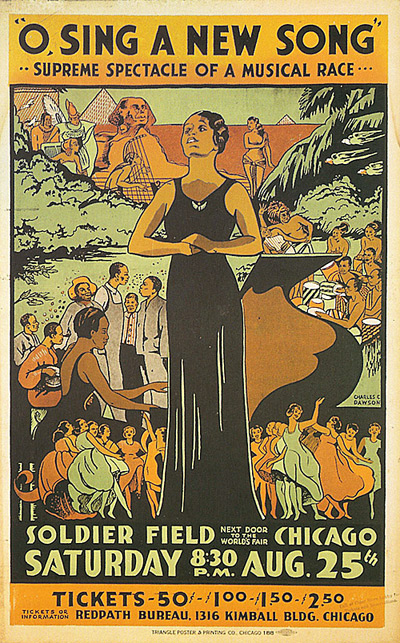

In year two of the fair, he was commissioned to design the official poster for a show celebrating black music and titled it “O, Sing A New Song.” Working for the Works Progress Administration in 1940, he built dioramas reflecting black history for the American Negro Exposition in Chicago.

Around this time, Dawson self-published a children’s book on important black achievers titled “ABCs of Great Negroes” with 26 linocut prints. He completed a watercolor of boys shooting marbles titled “The Crisis” in 1933 – a work that was not kindly accepted by all.

“The painting depicts a group of Negro and white boys playing marbles – in fact they’re down to the last one. That’s why I called it ‘The Crisis.’ But the Negro boys aren’t real black and they don’t look tough or have patches on their clothes. And they aren’t playing craps, but marbles. White people didn’t like that. They wanted to hold onto the stereotype as to what constitutes a Negro. I’ve decided in all my years to undo that stereotype, to try – like Ignacio Zuloaga, the great Spanish painter who showed the beauty of his people – to show the beauty and the wide variety of my people.”

Dawson is believed to have started working with Valmor in the 1930s. While Neumann the owner was an avid collector of mainstream artists, one writer noted, he ignored the talents of the designers who created the illustrations that made him rich enough to buy the others.

He was apparently married at some point; I found a postcard online that he designed with the inscription “Mr. and Mrs. Charles C. Dawson.”

In 1944, Dawson returned to Tuskegee University as an arts curator for its Museum of Negro Art and Culture at the George Washington Carver Museum, where the dioramas were eventually installed. He stayed there until he retired in 1951 and moved to New Hope, PA, to where African American artist Selma Burke had moved in 1947. Dawson died in 1981.

None of the articles about his life mentioned whether or not he painted or what he did after moving to New Hope, in Bucks County, PA. His original papers are in the collection of the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago and microfilm copies are in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian in Washington.