The history of black folks in America can be so elusive. Every now and then, I come across an item at auction that seems to have no connection to black history and with a little digging I get a bite. That was the case when I came across a bright yellow wringer washing machine that led me to an African American woman named Ellen F. Eglin who had perfected the wringer in her own way.

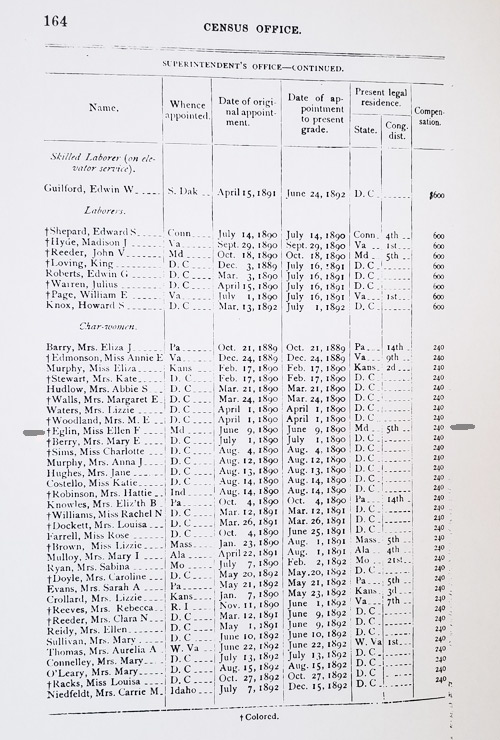

In researching Eglin, I also learned that she worked at the U.S. Census office in the 1890s, which I found intriguing. So I was curious about what her duties were, since this was the period of Reconstruction and a lot had changed in the country. But how much? I found her listed as a “charwoman” among appointees to the office. She was hired in June at a salary of $240 to work as an office cleaner.

Eglin is best known for the wringer, whose rights she sold because she knew it would be difficult to patent and sell the product. White women would not buy it if they knew it was invented by a black woman, she said.

Little is known about Eglin, so I’m not sure how long she remained at the census office. She arrived there 10 years after the civil service system was instituted whereby a test would be used to determine who gets hired rather than” who you knew.”

She was among the black men and women who held such jobs as charwoman, messenger acting as firemen, assistant messenger, skilled and unskilled laborer, and computer worker. They were not the first, though. Two decades before, a man named John Henry Smythe (his name is spelled without the “e” in some places) had already found a way in.

I stumbled onto Smythe’s name among a list compiled a few years ago by my friend Rebecca. He began working as a census clerk in 1870, the first tally taken after slavery was abolished. The U.S. census was a pen, ink and paper operation. Since 1790, U.S. marshals were the census -takers, or enumerators, roaming the country with instructions on what to ask and how to ask. The 1870 census – held from June 1870 to August 1871- was the last to use federal marshals, who were replaced by assistant marshals whom they appointed.

The information gathered by the assistants was sent to clerks such as Smythe in Washington who tabulated the information by hand.

Smythe was born in Richmond, VA, in 1844 and was sent to Philadelphia to get an education, but later went back South after his father died. He returned to Philadelphia in 1859 and attended the Institute for Colored Youth (which later became Cheyney University). He studied painting as the first black student to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He later painted fine china for a company in Philadelphia before heading off to London in 1865 to become an actor.

When that didn’t work out, he returned to the United States where he got a law degree at Howard University in Washington and landed a job first at the Freedman’s Bureau and then the census office.

Around 1870, the census office began hiring blacks as clerks, census-takers and other white-collar workers under its new superintendent Francis A. Walker, according to the census website. Walker relied on tests rather than patronage for jobs, and many of those who passed tests for that year’s census positions were African Americans and women. A newly invented tabulating machine eased the process of tabulating the data and by 1872 the work was done. Smythe moved on to other jobs in the government and elsewhere, and eventually was named ambassador to Liberia.

For the 1880 census, the marshals were replaced by trained census-takers.

After the civil service system was instituted in 1883, blacks saw it as a way into government employment and better pay. The census office was one of those places, where clerks earned a starting salary of $1,200 a year in 1900. African Americans faced discrimination but stuck with it, sometimes moving up in the office. Many had come north to attend Howard University, and came into these jobs with law and other degrees.

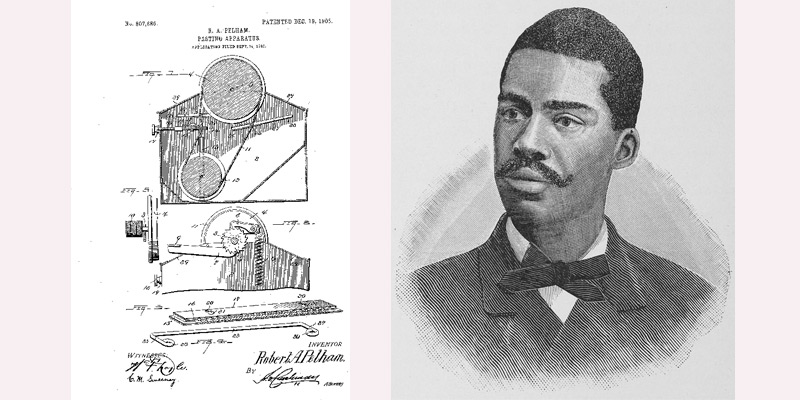

Among the early clerks were Ocea Taylor, Robert A. Pelham, William Jennifer and Charles E. Hall, who was described in a 1937 Crisis magazine article as “the senior specialist on Negro statistics.” He was said to be the first African American to be given a supervisory role over black census workers.

For at least three years starting in 1904 up to 1918, Hall, Pelham and Jennnfer supervised a group of black census workers who tabulated the numbers for a report on the African American population in the country. The 1918 report covered the years 1790 to 1915.

Pelham, who spent 30 years at the bureau and was also a journalist, invented a pasting device in 1905 for which he got a patent, and devised a tallying machine in 1913.

Sherry, I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed your article on the census and early black employees. I am a heavy user of the census due to my interest in finding out more about my ancestors and so any nuances about the census are also helpful in reading census data. But as usual you bring so much more to the topic then just basic facts.

Just as a side note about the richness of census data, in finding my great grandfather Calvin Walker in the 1870 census of Charlotte North Carolina, I was amazed to find a 90 year old woman named Nancy Springs living in the household of Aurther Walker, who lived close to my great grandfather. This woman gave her birthplace as Africa and I started immediately researching her to see if I could find out if we were related and where she came from in Africa. I won’t go into a lot of detail but I was able to out a lot more about Ms. Nancy Springs!!

But, back to your article, I truly appreciated your article very much as i do each and every story you tell us and please keep on doing what you doing, sister!

Thanks, Ruth.