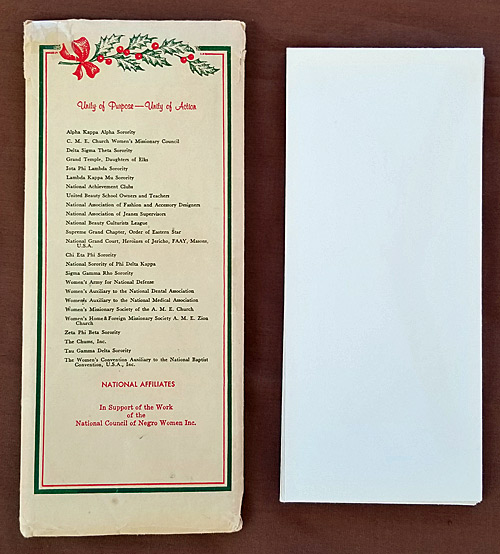

As I flipped through a box of auction items I didn’t remember buying, I came upon a bulging tan envelope with a Christmas wreath at the top and the names of African American organizations under the slogan “Unity of Purpose – Unity of Action.” At the bottom was the name “National Council of Negro Women.”

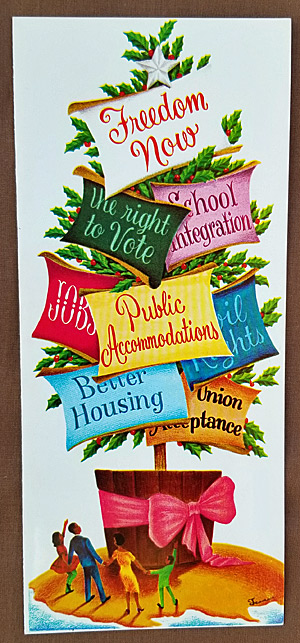

Opening the envelope, I pulled out a set of Christmas cards with an African American family looking up at a tree decorated not with ornaments and lights but with large placards bearing demanding phrases:

Freedom Now, The right to vote, School integration, Public Accommodations, Jobs, Better Housing, Civil Rights, Union acceptance

I knew these were the rights that African Americans had long fought for, but I’d never seen them displayed in this way. The envelope contained 10 cards and eight envelopes, all in good condition.

The NCNW, I learned, developed the cards to help raise scholarship money for black students whose financial aid was stripped after they participated in civil-rights activities or needed financial aid help. In the fall of 1964, the group stated that it would sell six million of these “Freedom” Christmas cards for that purpose. By 1966, 72 students had been award scholarships.

The cards were being sold against the backdrop of the civil rights movement and the Civil Rights Act, which had been passed by Congress and signed by President Johnson on July 2, 1964. Thousands of students had participated in marches and sit-ins in their towns or left colleges to agitate for their own rights, either individually or through the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

As Johnson signed the bill into law, NCNW president Dorothy Height was one of the many people at the ceremony. A few years ago, a fountain pen was found in the NCNW archives that is believed to be one of the more than 75 pens Johnson used to sign the bill that day.

The scholarships were awarded to several members of the Nonviolent Action Group, a SNCC affiliate, at Howard University, including members Stokely Carmichael, Ed Brown and Courtland Cox.

Another recipient was William Porter, who was expelled from Albany State College in Georgia but later readmitted. The money was used to pay his tuition. Porter had left the college to work full time as a SNCC volunteer but stayed out longer that he expected. As SNCC’s southern fundraiser and campus coordinator, he secured scholarship money for returning students who had worked in the movement.

NCNW also paid the tuition for Harvey Gantt, who in 1963 was the first black student to attend his hometown Clemson University in South Carolina but only after suing the university, and Lucinda Brawley, the first black female student who arrived some months later. Gantt, who years later became mayor of Charlotte, NC, and Brawley eventually wed.

Other scholarships went to Marion Barry, who later became mayor of Washington, DC, to pay his graduate-school tuition and Endesha Ida Mae Holland of Greenwood, MS, who used the money for tuition for vocational college. Holland went on to earn a doctorate degree and establish the African Studies department at the University of Minnesota.

NCNW has long been involved in the fight against discrimination, beginning with its founding by educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune in 1935. During the 1960s, it was perhaps the largest African American women’s organization in the country under Height’s dynamic and vocal leadership, and remained a force. The group was continuing a practice begun in the 19th century by Mary Church Terrell and the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. “Colored women are the only group in this country who have two heavy handicaps to overcome, that of race as well as that of sex,” said Church, the founder.

They are words that could easily have been said in the 20th century by Height, a protégé of Bethune’s who led the NCNW from 1957 to 1997.

Height and the NCNW were on the front lines of the civil rights struggle alongside the men – although they were not always acknowledged for their participation. They helped organize “Wednesdays in Mississippi,” an interracial group of northern women who traveled to the state as part of Freedom Summer in 1964. Height and New York civil rights activist Polly Cowan pulled the group together.

For three years, they worked with black women on housing, education, hunger and self-empowerment in one of the most vicious and segregationist states in the country.

“Many groups came into Mississippi,” Height is quoted as saying in the 2012 book “Black Women and Politics in New York City.” “NCNW never left. … Whether it was carrying books and art supplies to the Freedom Schools during Wednesdays in Mississippi, keeping Head Start on track, setting up pig banks, or building houses, we were helping people meet their needs, on their own terms. Women knew that if they joined the National Council of Negro Women they were going to help themselves by helping others.”

In an effort to alleviate hunger, the NCNW provided pigs, wire for pens, instructions and other assistance to help families provide their own food.

As head of NCNW, she was involved in the planning of the 1963 March on Washington. She and NCNW members went down to Selma when hundreds of children protesters were jailed. She went to Birmingham to console mothers soon after the bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls in 1963.

Height was the only woman standing near the podium when Dr. Martin Luther King gave his “I Have A Dream” speech at the march. Only one woman was allowed to speak – Arkansas civil rights activist Daisy Bates, after the chosen speaker Myrlie Evers was tied up in traffic. The only woman on the march committee, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, had to force the men to allow a woman to speak that day.

“The National Council of Negro Women has been there even when our story has not been told,” Height said in a 1979 speech at a symposium on NCNW history. “You may remember that in the summer of 1963, there was a great march on Washington. We were there. We did something that we were asked not to do, but it was too late when we heard they were asking that no one meet after the march on Washington (the men of the march met with President Johnson).

“We held a meeting called ‘After the March, What?’ And out of that meeting, there came a molding of some new spirits and new interests. So that by 1964, when Bob Moses called for the summer in Mississippi, the freedom schools, we had a coalition of women already working together, and those women went down into Mississippi on Wednesdays.”