I was rummaging through the loads of documents, photos and other papers I’ve picked up at auction over the years and found a portfolio of four reproduction prints by African American artist Charles White.

They reminded me that White was one of those artists who converted their works into reproductions, lithographs and serigraphs to make them affordable to more people. White was said to have produced at least five portfolios of small reproductions of his powerful ink-and-charcoal drawings, the first set in 1953 that sold for $3.

White began reproducing the drawings after realizing that only upper middle-class people and a few museums could afford them – not the black folks whose experiences he was chronicling. At the time, not a lot of museums or galleries were showing or buying his works or those of other African American artists.

“The primary audience that I was addressing myself to was the masses of black people, and they were not turning out in the hundreds to see my shows, and I had to find some way of reaching them, since my subject matter was related to them and should be made available to them,” he said in a 1971 catalog for an exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

White was known for his paintings, drawings and prints pertaining to the African American experience. He also illustrated dust jackets for books, as well as magazine and record covers. His drawing “Preacher” was on the cover of the February 1952 issue of Paul Robeson’s newspaper Freedom. He drew a sea of black women’s faces for the August 1966 cover of Ebony magazine’s special issue on “The Negro Woman.”

He was not much different from the Mexican muralists/painters of the 1940s – David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, who were also creating art of the people. In 1946, White and his wife artist Elizabeth Catlett went to Mexico where they both produced lithographs at the Taller de Grafica Popular (The People’s Print Workshop) in Mexico City.

During his two years there, White got to know and work with all three, influenced by their belief that art should have a broad reach. White felt an affinity for them because they all saw the world through the same lens. Like them, White made “images that are meaningful to me, images that are closest to me.”

Back in the United States, he published lithographs while at the Workshop of Graphic Art in New York. The idea of printmaking wasn’t new to him; he had been excited about creating lithographs since he was 17 years old, he said, but never had a real opportunity to work with the process.

White got a chance to do reproductions of six of his 15 drawings from a solo exhibit at the ACA Galleries in New York in 1953.

The portfolio was titled “Charles White – Six Drawings,” published in 1953, with an introduction by artist Rockwell Kent. There were 13″ x 18″ loose-sheet reproductions of “The Mother,” “Dawn of Life,” “Let’s Walk Together,” “Harvest Talk,” “Abraham Lincoln” and “Ye Shall Inherit the Earth” – whose original sold at Sotheby’s last year for $1.8 million (with fees).

The portfolio was apparently a hit among the folks White was going after: He reportedly learned that some black workers in Alabama had chipped in, bought a portfolio and shared the prints.

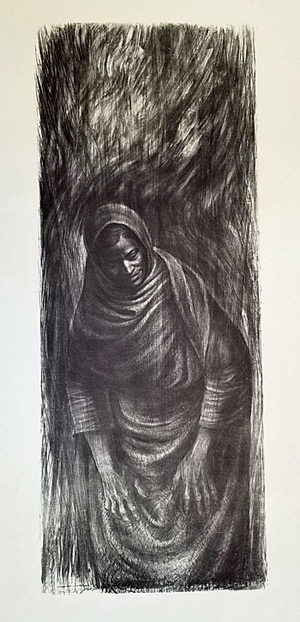

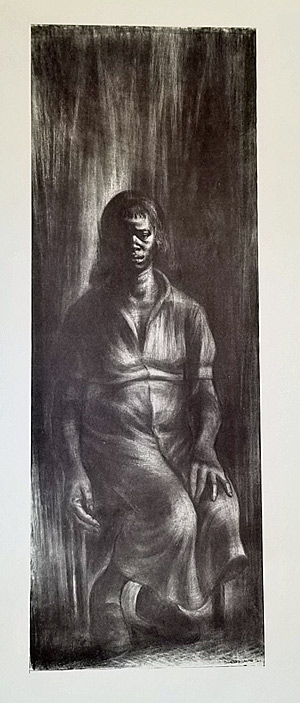

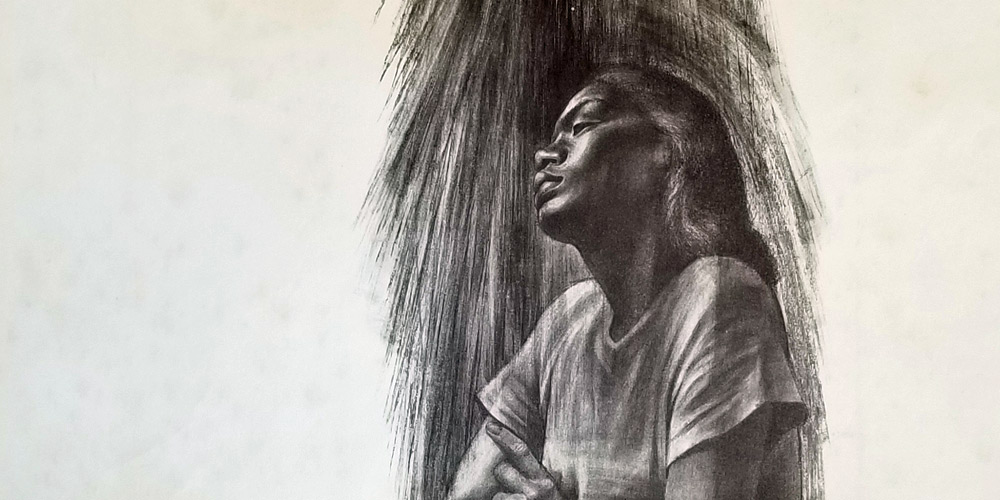

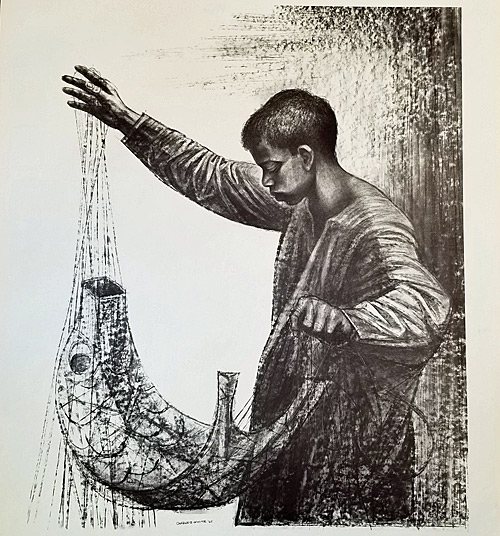

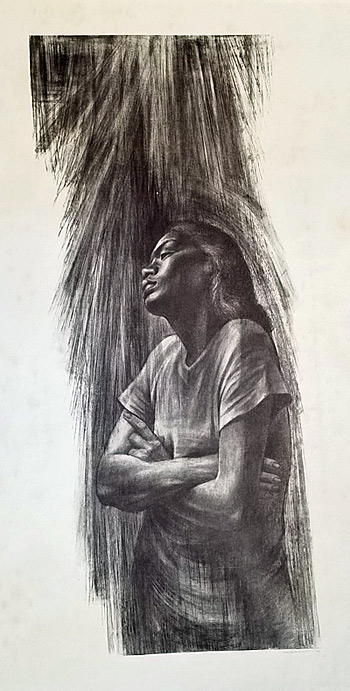

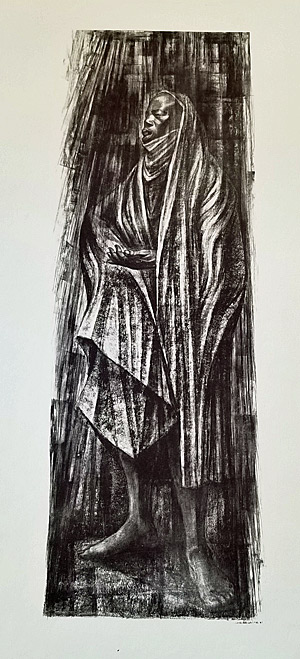

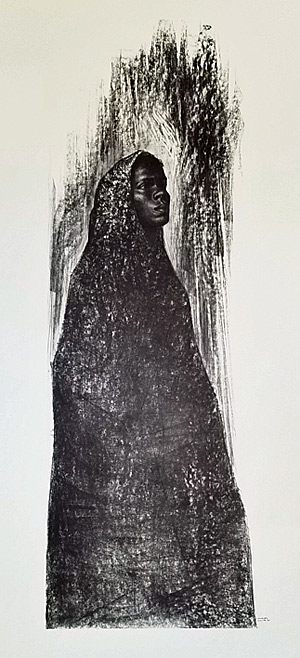

The reproductions I found among my papers were part of a set of 10 published in 1961 titled “10 / Charles White.” I have six of them: “Mayibuye Africa,” “Go Tell It On the Mountain,” “Flying Fish,” “Let the Light Enter,” “Birth of Spring” and “Nocturne.” Missing are “Southern News: Late Edition,” “Awaken From the Unknowing,” “C’est L’amour” and “Move On Up a Little Higher.”

Singer and actor Harry Belafonte, a friend and early collector of White’s works, wrote the introduction.

White was said have produced another portfolio of six drawings in 1964.

In 1969, he published “I Have A Dream” in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The portfolio held six prints, including “I Have Seen Black Hands,” “Vision” and a study of “Silent Song.” The set sold for $15 plus postage.

Most of the portfolios may still be affordable for a lot more black people than in the 1950s and 1960s, even at inflation prices. Those reproductions, though, are not as valuable as White’s lithographs, which for some are still in a reasonable price range.

“My whole purpose in art is to make a positive statement about mankind, all mankind, an affirmation of humanity,” White said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1964, as Kellie Jones noted in her book “South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. “This doesn’t mean that I’m a man without angers – I’ve had my work in museums where I wasn’t allowed to see it – but what I pour into my work is the challenge of how beautiful life can be.”