As I drove down the narrow one-way street tight with cars on both sides, I kept an eye out for artist Dindga McCannon’s house. Look for the purple steps, she had told me after I accosted her at a New York auction where her painting “The Last Farewell” had just sold for $130,000.

Not only were the steps to her rowhouse in South Philadelphia the color purple, but so was the door. There was no way to miss it.

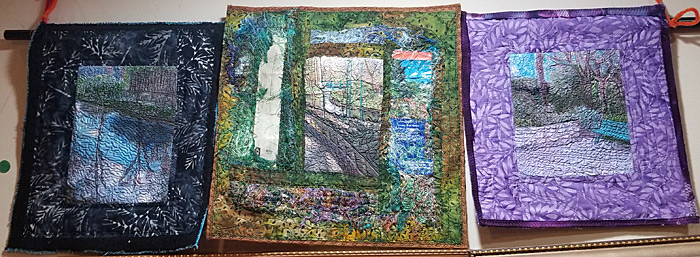

The interior of her house was just as vibrant, the walls loaded with warm and colorful quilts. I wasn’t expecting to see so many quilts especially since she was represented at the auction by a painting.

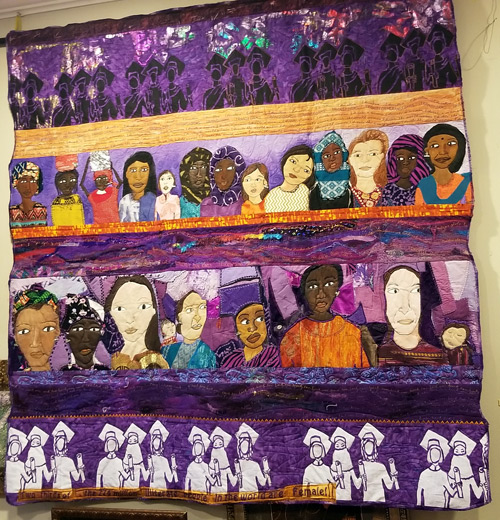

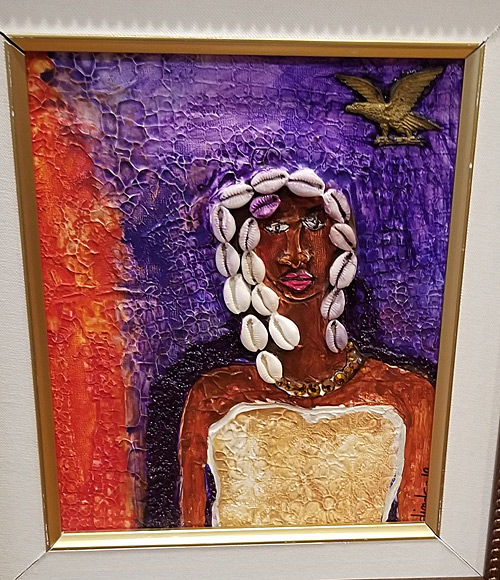

McCannon has hung a smorgasbord of large quilts, most bearing the faces of black women – sheroes rather than heroes; small quilts of landscapes inspired by Claude Monet’s Garden at Giverny and quilts pertaining to her family’s heritage.

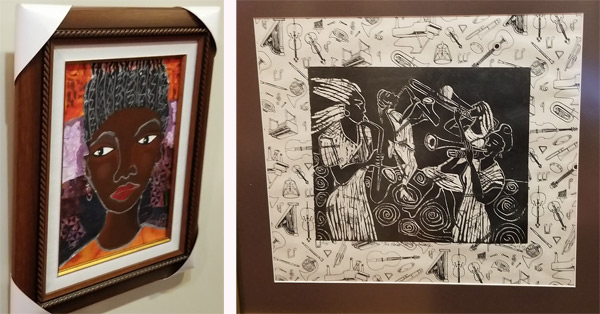

Between her sofa and dining room table was a rack of clothes she had sewn for sale, and almost hidden near the door were terracotta pots of fabric flowers, one of which won her first place some years ago in a needlecraft contest. A handful of prints were interspersed among the works on the walls.

She is one of those artists who paved the path for contemporary black artists, some of whose works are finally being accepted as worthy of attention. It was not so in the 1960s and 1970s when artists like her could barely find a spot on the walls of major galleries and museums or collectors willing to buy their works. Many of them are names that very few remember.

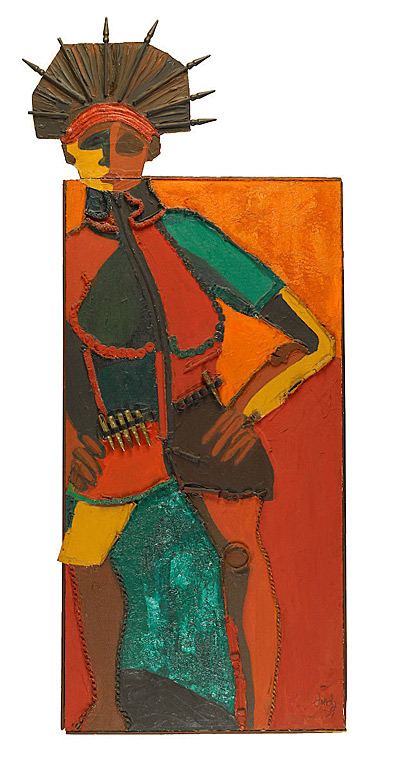

Despite the sparse recognition, McCannon has kept at it. She has always created art to represent the power of women, her primary subject of choice since the beginning. She feels entrusted to tell their story, she says, because it is her story. She refers to her works not as “it” or “they,” but as “she” and “her.”

“I call myself a womanist,” she says. “I’m really interested in their lives, their histories, the stories of African American women.

“A lot of the black artists, particularly at that time, were men so they focused on things that men were interested in. So, I being a woman focused on things that I was interested in, which is what other women are doing, have done, have created and how we continue to push through barriers. Under the most stringent and sometimes bad circumstances, we still seem to be able to accomplish things.”

McCannon describes herself as a mixed-media artist. She makes jewelry, creates etchings and works in linoleum. She’s painted murals in New York, where she was born in 1947 in Harlem, helped create a women’s arts collective in the 1970s, and six years ago moved to Philadelphia, figuring that rents were cheaper and making a living as an artist was more doable.

She works primarily in textiles and is in the process of making prints of some of her earlier paintings. Her works are textured – with sequins, stones, shells, buttons, beads, metal pieces and even paper. In that sense, she says, they are different from her well-known counterpart Faith Ringgold, whose story quilts are internationally known.

Here’s the trajectory of McCannon’s life:

Connecting with the Weusi art collective

“I was a young artist. My 16th summer, I couldn’t find a job so I ended up working as a volunteer for the American Red Cross and they sent me to a school right down from the block where I lived on at 121st Street. The director there saw that I was very much into art, so he let me teach art classes. That was probably my first art job.

“Then one day, he came in and he said, this weekend I went out to 127th Street and St. Nicholas and I saw all these artists hanging their artwork up on the fences. He said you should probably go over there, they might be able to help you.

“So, the next Saturday of course I was right over there. At the time there were maybe 50 artists who hung their work on the fence. At the time the group was called Twentieth Century Art Creators and they kind of took me in and they showed me the artistic ropes. Through them I had my first exhibition. The group had a dispute and they split. One half remained Twentieth Century Art Creators and the other half became ultimately Weusi.”

Weusi was an arts collective founded in 1965 by African American artists who sought to create art that represented their own culture and heritage, thereby becoming a part of that era’s Black Arts Movement. They were based in New York but had counterparts in other major U.S. cities, including AfriCOBRA in Chicago and Spiral, formed in the early 1960s by artists Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Hale Woodruff, Emma Amos and others.

Weusi held exhibitions at its New York gallery called the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery (later renamed) that exhibited African American and African artists, said McCannon, who is still a member.

The group was active in speaking out and agitating for black artists. It was among the groups that protested a 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968” that neglected to include Harlem residents in the planning and failed to include works by African American artists. Weusi artists also participated in a 1971 alternative exhibit titled “Rebuttal” at the black-owned Acts of Art Gallery in response to a decision by the Whitney Museum of American Art not to hire a black curator for its show on contemporary black artists.

Around that time, McCannon joined other black female artists to form a group for themselves.

Where We At art collective

“During the late ’60s, I was a woman artist basically living in a man’s world. Everything was fine until I had a child because that presented a whole bunch of other issues like who was going to take care of that child while I was in the studio because at that time care of the children in probably 80 percent of the households was left to the woman.

“So, I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to negotiate all of this. … I said other women artists must be experiencing this. So I called Kay (Brown) and she called Faith (Ringgold) – I don’t remember who called who first – anyhow we all called each other and we said let’s get a group of women together, black women who are artists and let’s have a conversation.

“So, each one of us called whoever we could find and it ended up like 10 women came up to my apartment, which was a top-floor walk-up. The hallways were dark, there was water dripping down. This was the Lower East Side. … Because of that first meeting, we ended up deciding why don’t we try to exhibit together because most problems that artists have are financial and as women we had the problem of how are we going to be creative and also raise children.

“I had had an exhibition at Acts of Art Gallery. The only way I got into Acts of Art gallery is because one of my male artist friends went to boot for me and told Nigel (L. Jackson, the owner) that yes, this seems to be the profession that I want. I’m not here on a whim. This is what I’m going to do. So Nigel let me have a show.

“I figure he might let us all in. We went to him and approached him, and he was all for the idea. And we had our first show” in 1971 titled “Where We At – Black Women Artists.” It featured 14 black female artists.

McCannon noted that Where We At held exhibits at the Weusi gallery and some women held shows in their homes. Where We At was a nonprofit organization that obtained grants to teach art in prisons and shelters. The women also babysat for each other, paid each other’s rent when money was short and encouraged each other. The group eventually disbanded years later.

Most of the black women artists were never really able to make a good living off their art. McCannon tells the story of Brown who she says died in a nursing home in Washington, DC, and her fear that Brown may have been buried in potter’s field.

“One of her pieces was in ‘Soul of a Nation (Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983),” which went to London and at the Tate. In my head I went to represent her because I knew that had she lived to see that moment, it would have validated her life struggle and work. It would’ve finally (showed) we’re going mainstream after all of these years. I really felt bad that she hadn’t made it to this point.”

The exhibit was organized by the Tate Modern in London in 2017 and has been on tour for the last three years. Brown’s painting “The Devil and His Game (1970)” is in the exhibit.

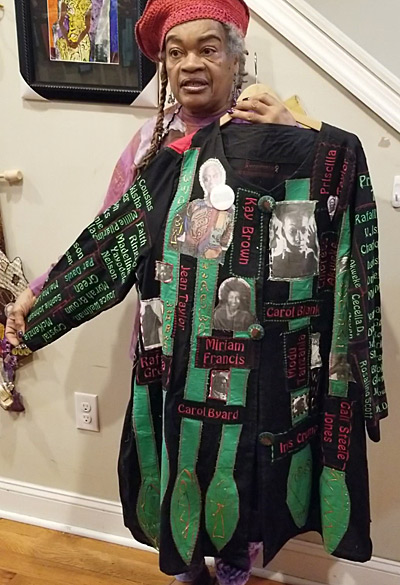

To represent the members of Where We At, McCannon sewed a beautiful coat in their honor for the exhibit “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85″ at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017. Her “Revolutionary Sister (1971),” which is in the museum’s collection, was part of the show.

“This is my ‘Where We At’ coat. Although I was grateful for the opportunity and the fact we were finally getting noticed while a few of us were still on the planet, I felt a little sorrow in the fact that a lot of the women, some had stopped working, some had passed on. So, I was trying to think of a way that on the opening day I could bring all of us to the table. So this is what I created. I researched who had left, who had passed. Everybody’s name is embroidered on the coat, and in back of it there are just memorable scenes and exhibitions.

“This way it was like bringing us all to the table. What we had was a sisterhood and like most sisterhoods we got along very well and sometimes that didn’t happen, but we still stuck together, supported one another, exhibited together, helped in getting opportunities for ourselves.”

Growing up to be an artist

McCannon didn’t necessarily sprout from an artistic family. Her mother and grandmother sewed and made their own clothes, but back then, those skills were not considered an art form. Her mother didn’t want her to become an artist because it would not pay the bills.

McCannon began drawing when she was about 9 or 10 and earnestly decided at age 12 that she was going to be an artist even though she knew of no black female artists. “It was a profession that beatniks, crazy people and other people go into (and couldn’t make a living from),” she says. “I think that first wave of artists in the ’60s, our idea was to be able to function as artists and to get our art out into the black community, make it affordable so more people could purchase it, which is why a lot of prints were done, a lot of posters. And over the years, we built an audience.”

She was educated by the Weusi artists and the Art Students League, but did not attend art school. She had her first exhibit with Weusi when she was 18 years old. To make money, she became very resourceful: She made and sold clothes, including dashikis that were “the” fashion for African Americans, and she taught herself how to make jewelry. She made the products and her husband, a Weusi member, sold them on weekends. They also operated two stores for a time.

“In the ’60s and the ’70s, black people or a certain segment of black folks became interested in African clothing (and) I as an artist found a really good medium in being able to do my art on fabric and selling it as wearable art,” she says.

McCannon has been an artist for 55 years, but has never reaped large sums for her work. Today, she says, she sells enough to “barely get by. … The sewing part of my life has definitely helped sustain the artistic part of my life.”

None of the money from the January auction of “The Last Farewell” – whose realized price was $161,000, which included the 25 percent buyer’s premium tacked on to auction purchases – will fill her pockets. The painting belonged to the Johnson Publishing Company, which bought it in the 1970s, and will be used to pay off the company’s debts.

“The nicest thing about being at that auction, you see that there’s really a lot of money out there that can be spent on art,” she says. “The problem is that we as black artists don’t always have access to those people. You know how many art shows I’ve been in and gone to and very little has sold.”

“There are a lot of (buyers) out there. You could see by the amount of black people who were at that auction. It was over half black and that was good to see because that verifies the fact there are people out there who want to spend money on artwork.”

Origin of the painting “The Last Farewell,” 1970

“I was dating a young man who was a lot younger than me and he was a student at RISD, the Rhode Island School of Design. And I was envious because that was my dream to go to art school and I never did that. I was educated basically by Weusi and the Art Students League. At one point in the relationship, I realized that this was it, this relationship is not going any farther. That last evening we spent together I knew intuitively without anybody saying anything this was the last farewell.

“That was it. And that was the two figures I created. I think I did two pieces with that same theme.”

During the auction, the auctioneer singled her out. “One of my clients was in the audience and I guess he had come to bid on that piece and maybe other pieces and of course he couldn’t afford it. When it got to a certain point he turned around and said to me I’m out Dindga, I can’t do this and that’s when the auctioneer said no bidding the artist up. That’s how everybody found out I was the artist whose work that was.”

“When my work went for that amount of money, I don’t know if I wanted to faint or scream. I think I wanted to do both. At the same time, I ain’t getting a dime. But the fact that somebody in the world think it’s worth that means that I should be able to get more money for the work that I currently do. So the jury is still out on that one.”

Her memory is a little fuzzy on the details of the sale to Johnson Publishing Company – it was 50 years ago. She suspects that the call went out and artists were asked to submit work, and the company chose “The Last Farewell” as one of its purchases.

“Then over the years whenever I would go to Chicago, I would go visit the piece,” she says. “I think it was in the fifth-floor ladies lounge room. I think I went up there to visit her twice over the years.”

Since the auction, she’s heard from a few people interested in her works, including a major gallery. Since she works in textiles, she wonders if that could be a hindrance because some people consider it women’s work and not “fine art.”

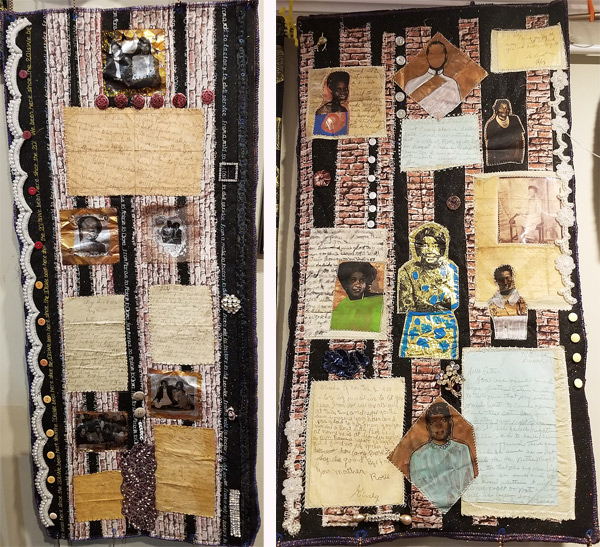

“Harlem Memories” quilt

“It started because I’m the elder in my family now. When my mother passed she had a big grocery bag full of stuff which I kept for 10 years before I could figure out what I wanted to do with it. I was a resident of Harlem. That’s what inspired it. Laurie Gadson who was a New York artist-quilter had a show called ‘Harlem Sewn Up’ (in 2009). Apparently, some of the new people who were moving into our neighborhood acted as though they invented Harlem. So I said this is the perfect time to show I’m a third-generation Harlemite and I began to pull out proof of gas bills from the ’30s, rent receipts from the ’20s, old photos and other kinds of memorabilia.

“A lot of time when the elders pass, the young people come in and they throw out everything, not knowing that this is living history they’re putting in the garbage.”

There are five works in the series, which were created from 2009 to 2012. Two of them hang on her walls and three were given to her granddaughter and cousins.

The art of getting old

One of the works on McCannon’s walls is what she called “a fun piece on aging.” It was a woman’s torso made of paper, sequins and stones. From the bottom hung strips with absurdities pertaining to getting old.

Getting old as an artist is hard, she says, because many don’t have pensions and other benefits. And some have a difficult time dealing with the psychological issue of not having “made it” in their craft. Philadelphia, she notes, does have benefits to help its elderly.

The artwork is titled “I Embrace The Older Person That I’ve Become” and was done about seven years ago.

“All of these are the things that happen to you when you age,” she says. “I went into a fabric store and the man said, ‘I hate old people.’ Of course, we didn’t get along after that.”

She explained the strips as she read them:

– “You don’t get any earned income credits after 65 because they assume you’re nicely retired and not working.

– Silver is not a curse word to me because it’s a whole other thing about hair. Everybody dyes their hair and it’s quite evident that you are old. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it, but I’m just saying.

– Welcome to pill world ‘cause we’re all on some kind of meds.

– Let your son fill out the form online, assuming that you don’t know anything about the computer.”

The torso is made from “a lot of found stuff from the scrapbooking aisle. This is paper, the actual paper pulp. I can make paper but I discovered they have paper in a bottle and bought me about 10 bottles and all you do is change the color, slap it on and let it dry.”

What a fab lady I loved reading about her & love her work. I’m a white English old woman & make textile art & thanks to the internet I can read about a gutsy Americanlady. To girl