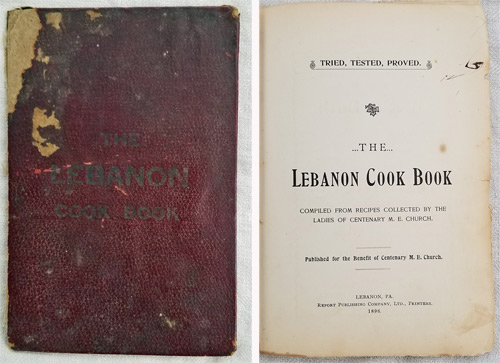

The cookbook was a mess. Its cover was so dusty that I could barely read the title. Its spine was unglued, its pages were brittle and pockmarked with brown stains – which surely were made by greasy hands – and its front cover had fallen off.

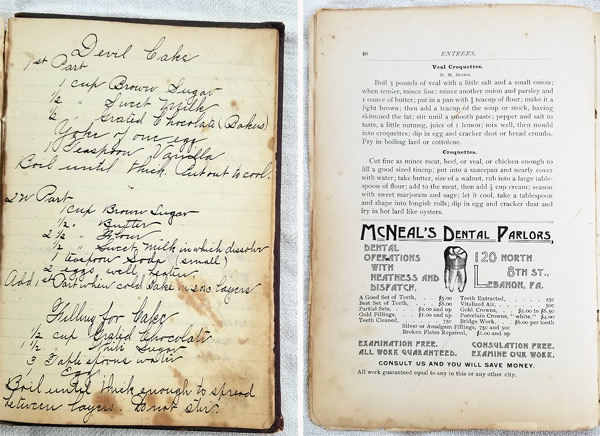

But for me, that was all cosmetic. Looking at the book with its warts, I knew it had been loved. One woman who had handled it had written her own recipes in pencil and fountain pen ink on blank pages, and on loose sheets of paper.

I found this church cookbook a few years ago among a group I had bought at auction. I love cookbooks and have a few old ones that I’ve picked up over the years, including Aunt Julia’s cookbook and Freda DeKnight’s Ebony cookbook.

This hardback book was titled “The Lebanon Cook Book,” compiled by the “Ladies of Centenary M.E. Church” to benefit their Lebanon, PA, church. It was printed in 1896 by Report Publishing Company, which also owned the local newspaper. The names of two women were written on another page in the book along with the date 1908.

Tucked near the front was also a sparse 1918 wartime conservation pamphlet from the New York State Food Commission with text and recipes for beans, and another from the U.S. Food Administration on the many ways to use cornmeal.

As I gingerly turned the delicate pages, I found something else just as intriguing as the recipes. The book contained half- and full-page ads, mostly for Lebanon companies. These were not only ads for groceries, clothing and items normally ascribed to women. They ranged from coal, gasoline and oil to banks to buggies/carriages to guns to Mount Gretna Park, a summer mountain retreat.

In the prime space near the front of the book – where I’m sure the ad prices were higher – Dr. Geo. Ross & Co., Druggists, touted their “pure” products for baking cakes: cream of tartar, baking soda, spices and flavorings.

J.K. Knerr says he was the “Dealer in the Best Grades of … Family Coal.”

Bensing & Bro. Grocers pushed their “own” cold boiled ham, potted ham, potted tongue and pickled spiced celery, as well as “bottled” pickles, olives and chow chow.

Mish’s Greenhouses had palms and ornamental foliage plants “for Sale and to Let.”

Frantz’s Furniture Bazaar proffered “Special Inducements Given to Young Housekeepers.”

Miller Organ Co. wondered “Why Not Buy The Finest and Best … Organ” from them.

O. Detweiler offered “Mackintoshes – and Clothing for Gentlemen and Ladies.” Mackintosh is a raincoat.

Churches were among the first to produce cookbooks (the first actual cookbook appeared in 1864 to help pay the medical expenses of Union soldiers during the Civil War).

Soliciting ads became one of the best ways for churches to raise money through their cookbooks, according to an article in Peterson’s Magazine in 1892. “Patent-medicine men long ago realized the advantage of advertising their nostrums side by side with fruit-cake, jellied chicken, and other recipes for dainty dishes,” stated writer Annie Curd in the article “How to Get out A Church Cook-Book.”

Curd offered some advice on how to coordinate the project: Set up a committee of no more than five people whose job was to give it a name, decide the number of pages, type of paper and price, and sell advertising.

“A nice edition to a cook-book is an appropriate motto or familiar quotation, as a heading for the different departments,” she wrote. “It adds spice to the already spicy contents, and gives a pleasing turn to the otherwise prosy and monotonous task of preparing three meals daily.” The Lebanon cookbook contained quotes from Shakespeare, Pericles and others. It also included a section with home remedies.

She recommended a printing of 2,000 to 2,500 copies with recipes solicited from the congregation. Donor’s name or initials are noted with most recipes in the Lebanon book.

The committee women sold the ads, hustling businesses who presumably understood their importance as consumers. I suspect that they knew many of these business owners as customers or fellow church members. All of the ads in the cookbook, except one, were local, including the printer of the book who bought a full-page ad. Advertisers paid no more than $2 to $3, Curd noted, and some paid less than a dollar.

“One of the most successfully managed cook-books I have ever known contained 160 pages, forty of which were devoted to advertisements,” she wrote. “Two thousand copies cost the committee one hundred and seventy five dollars, and, before the book was sold, they had paid the publisher’s bill and deposited seventy dollars in bank, the proceeds of the advertisements.”

The Lebanon cookbook had 200 pages and about 34 half and full pages of ads.

Here are some of the other ads in the cookbook: