The two sisters had come to the auction with enough money – they thought – to buy a painting by their Uncle Henry. They wanted to give it to his grand-daughter.

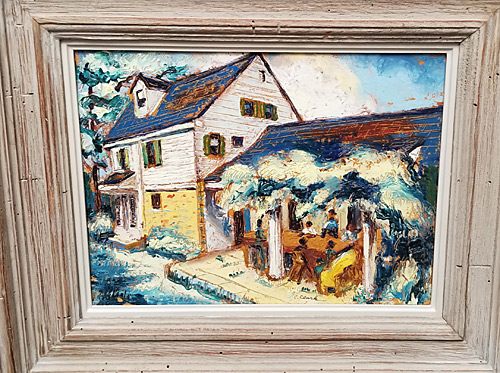

They waited and waited until the painting – titled “Banks of Chaloon (1929)” – finally came up for auction and raised their bid number as the price moved closer to their limit. They finally gave up as two bidders – one sitting in the audience and at least one other online – went tit-for-tat over the oil painting by Henry Bozeman Jones.

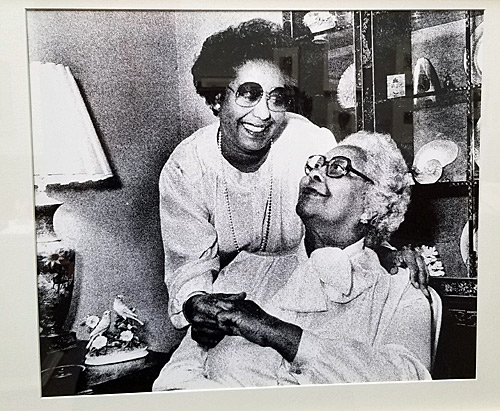

By the time the bidding ended, Constance E. Clayton walked away with it. I recognized her because she was the former superintendent of Philadelphia’s public schools, its first black leader. I didn’t know, though, that she was an avid art collector who was a lover of African American art and an advocate for the artists.

Clayton was a longtime bidder, one of the staffers told me, and had attended their auctions long before I started showing up.

After seeing the exhibit “Awakening: The Collection of Dr. Constance E. Clayton” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) recently, I realized why she wouldn’t budge on the Bozeman painting. She was a woman on a mission, and this lovely landscape by a Philadelphia African American artist fit well in her collection.

Clayton and her mother Williabell Clayton were historians-of-sorts, capturing and celebrating the works of African American artists from the 19th through 20th centuries. In interviews, she has said that they also collected what they liked and wanted to live with.

I understand that need to ensure that African American artists occupy their rightful place in a history that has traditionally denied them entry. I have artworks by some of the same artists in my own collection, and I bought them – most at auction – because I loved them and wanted to write about them and learn about them and give them a presence.

PAFA’s exhibit of 76 paintings, prints and sculptures can be seen in three galleries in its Historic Landmark Building in Philadelphia. It is a “celebration of family, women and the lives of people,” as co-curator Brooke Davis Anderson described it. Alongside the artworks are texts by 15 community people offering insights into each of them. The museum is also offering talks, panels and tours as part of the exhibition, which runs until July 12, 2020.

The academy acquired the artworks after Clayton reached out to them and invited them into her home, said Anderson. Last year, Clayton donated 78 works (two are not included in the exhibit because they were not created by African American artists). In 2015, she gave some artworks to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York, which held an exhibit titled “A Labor of Love: The Art Collection of Dr. Constance E. Clayton” late last year.

This treasure trove was a major donation for PAFA. Anderson and co-curators David Brigham, the academy’s president, and Sarah Spencer, an assistant who is a master’s candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, were effusive at having been chosen to receive it. It added new artists to PAFA’s collection (18), increased its holdings of African American artists and included some former students (seven of them, including Barkley L. Hendricks).

The academy “has a longtime commitment to the black experience in American art,” said Anderson. “Now we have new artists in this collection.”

PAFA’s relationship with black students who-would-be-artists goes back to the 1860s when John Henry Smythe became its first black student. Henry Ossawa Tanner enrolled in 1879 and his work “Nicodemus (1899)” was the first painting the academy purchased by an African American artist. The academy also had a relationship with artist Humbert Howard (who is also represented in the exhibit) and the Pyramid Club, an African American men’s social club founded in 1937 that held art exhibits for black and white artists.

Anderson noted that PAFA has never had a painting by Charles White, three of which are in the exhibit, and she gushed about Augusta Savage’s “Gamin’,” also part of the exhibit. It is one of Savage’s most iconic and most-familiar sculptures. Exhibited alongside “Gamin'” is a bronze sculpture titled “Slave Boy,” attributed to a little-known sculptor named May Howard Jackson, a PAFA alumni and its first black female art student.

The exhibit introduced me to other works by artists whose names I was familiar with, and equally important by artists I had never heard of. Laura Wheeler Waring’s portrait titled “Four Friends” is a loving tribute to African American boys and girls. It was painted circa 1940 when black children were displayed in mainstream publications with very little dignity. (Anderson is seeking the public’s help in trying to identify the children.)

Wheeler was a graduate of PAFA, and directed the art and music departments at Cheyney State Teachers College (now Cheyney University). She won a PAFA scholarship to travel to Europe in 1914. The Pyramid Club’s 1948 exhibit was held in memoriam to Wheeler, who had died that year.

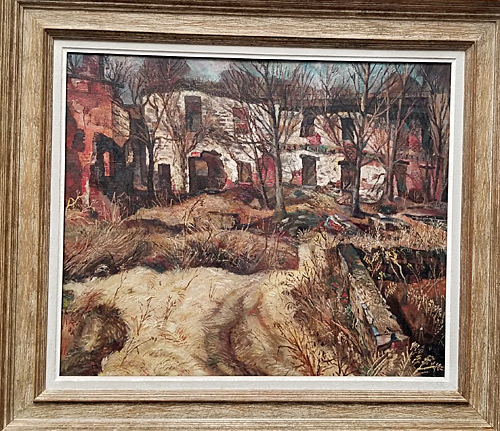

The exhibit includes multiple paintings by Dox Trash, most of them portraits, and Louis B. Sloan, who was known for taking his canvas and his students out into nature to paint. Hendricks was one of Sloan’s students at PAFA, where Sloan taught starting in 1962. Another artist represented in the exhibit is Edward L. Loper Sr. of Delaware, one of my favorites.

Two artists were unknown to me but a pleasure to meet: Bessie Ruth Bridges (“Untitled (Street Scene),” no date, and Henry L. Stevens Jr. (“Old House Germantown,” circa 1933). I presumed that both were Philadelphia artists; I could find no information about them. A surprise painting was Palmer Hayden’s “Turning Them Over,” a watercolor of a white man seated on a bench feeding birds. I’d only seen paintings of his featuring black people, including “The Janitor Who Paints (1930).”

Clayton and her mother collected art together for years, and she continues to buy (her mother died in 2004). The pieces were purchased at auctions, galleries and salons at their home, according to Anderson.

She was inspired by the collection of lawyer and civil rights activist Sadie Tanner Alexander, whose walls included works by her uncle, Henry Ossawa Tanner, said Spencer, recalling comments Clayton wrote in the catalog for “Represent.”

Clayton served on the board of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and founded its African American Collections Committee in 2000. She was instrumental in the mounting of two exhibits at the museum, “Treasures of Ancient Nigeria” in 1982 and “Represent: 200 Years of African American Art” in 2015.

She contributed to the museum’s acquisition of Elizabeth Catlett’s sculpture “Mother and Child (1956)” in 2000.

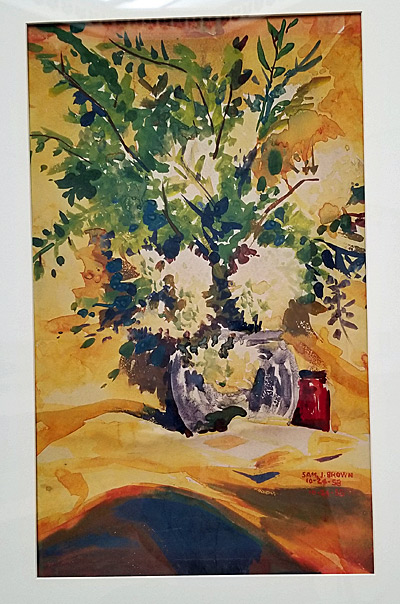

Other works in the exhibit: