The first thing I saw as I walked into the church community center was a huge wall with multicolored images featuring a man’s brown face surrounded by puzzle pieces that appeared both cacophonous and distinct. As I looked around the room, I saw three other mosaics just as large and just as boisterous.

These mosaics – I first thought they were murals – were meant to be seen, their intricate details meant to subtly teach while innocuously being enjoyed.

I didn’t initially spend too much time with them because I had come to the women’s prayer breakfast at St. Paul’s Baptist Church in North Philadelphia because the pastor from Dayspring Community Church in the Washington, DC, area was speaking. My friend Minister Yvonne Shinhoster Lamb had invited me to come to hear her pastor, who is also a friend.

Like St. Paul’s minister, the speaker was a woman – Rev. Cynthia T. Turner – who with her former husband founded Dayspring 19 years ago. It is likely one of the few churches with a full slate of female leaders, including Lamb and Minister Tee Clark, who also came along. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of black female ministers like them and St. Paul’s Rev. Leslie D. Callahan, who was installed in 2009.

As usual, Turner was a wonderful and instructive speaker, imparting a message just as thoughtful as the mosaics on the walls. The artworks were not only enlightening but they exuded a strong sense of place.

Titled “Our Church – Our Community. Our City,” they were painted in 2009 by an organization called NetworkArts, according to a plaque on the wall. The artist was Ricki Lent, and the works also have the handprints of the Children of the Summer Day Camp at St. Paul’s Vacation Bible School. They were created by students in two summer camp projects, according to the organization’s website.

NetworkArts uses “mosaics as a language of learning and as a tool to help children value themselves and their communities,” according to its website. Its teachings about science and the environment and arts and humanities result in the creation of the mosaics. Founded in 1993, it is an international nonprofit organization that works with children who have the potential of becoming at-risk.

The mosaics can be found in such places in the Philadelphia area as schools, the zoo, the Franklin Institute science museum, the airport and nursing homes, Free Library, and in outside locations such as parks.

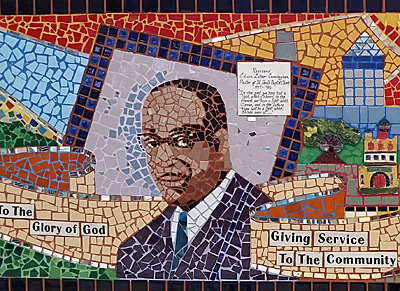

The ones at St. Paul’s lived up to the title. The first one I saw of the man’s bust was the only one with a definable human image. He was Rev. Edwin Luther Cunningham, who pastored the church from 1937 to 1964, according to a script written in cursive on a plaque on the wall. The community center bears his name. He stared out from the mosaic, the church building to his right, a bright sun over his left shoulder and above the Philadelphia skyline, and the church neighborhood on both sides.

Another mosaic celebrated the city’s extraordinary history and its sports teams through their logos: The Liberty Bell, the signing of the Declaration of Independence and Independence Hall, the Delaware River and its bridges, an Eagles head, the Phillies red “P” and the Sixers’ “76.”

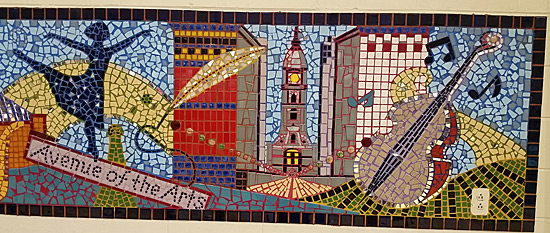

Another highlighted its music and more: Broad Street and the Avenue of the Arts leading down to City Hall, its arenas, a few tossed musical notes, a guitar, a saxophone and a brown figure beating an African drum.

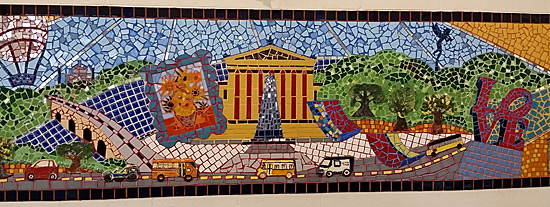

Another depicted its arts: The Philadelphia Museum of Art building right smack in the center, with cars, vans and buses representing visitors parked out front, Van Gogh’s famous “Sunflowers” painting, the LOVE statue and the hot air balloon over the Philadelphia Zoo.

Practically all of the mosaics bore small African American boys and girls among row houses and single homes in the foreground, and one pictured a tiny St. Paul’s church.