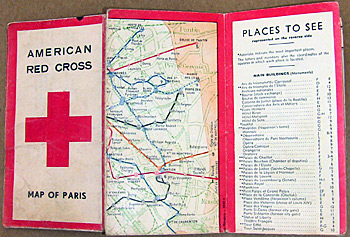

The map with the red cross was innocent enough. Anyone seeing the symbol would automatically know that it represented the American Red Cross before seeing the name across the top.

I didn’t think much about this “Map of Paris” as I unfolded it to take a closer look. It was among a plethora of World War I and II papers and other items in a box lot I had purchased at auction. I couldn’t wait to get the box home to see what treasures some soldier or his family had tossed.

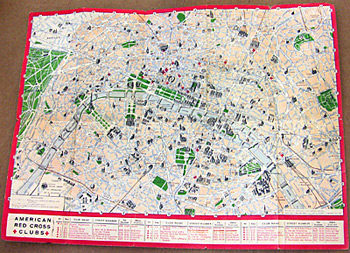

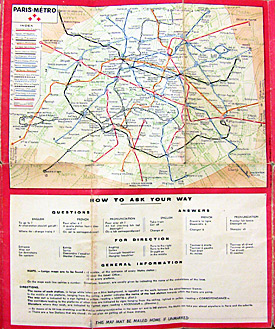

As I unfolded the map, I saw that it was a layout of Paris, its streets and metro systems, its tourist attractions and its famous Seine river that curved like an upside-down cup through the city. Then at the bottom in red lettering, I saw a list of Red Cross Clubs. Two instantly caught my eye:

Left Bank Club (Negro-Staffed), 1 bis, rue de Vaugirard

Potomac Club (Negro-Staffed), 11, rue de Lyon

These were the organization’s two clubs for African American soldiers among a total of 16 listed on the map, which bore the year 1945. Both were in the southeastern part of the city: One near the Sorbonne and the Jardin du Luxembourg in the Left Bank. The other was just across the Seine River to the east.

Now curious, I wanted to learn more about these clubs for black soldiers. I knew that Paris and France had always been a welcoming place for African Americans escaping racism in the United States. Artists and writers had been going there for years, many gravitating to a place where jazz reigned. Henry Ossawa Tanner found so much peace there in 1891 that he made France his home. In the 1920s and 1930s, Josephine Baker dazzled Parisiens with both her beauty and her audaciousness as an entertainer, and during World War II with her bravery in the French resistance.

So I’m sure that black GI’s on furlough found solace there, too, even if some of it was in segregated clubs operated by the American Red Cross. It was perhaps at these clubs that they were handed maps of Paris and other cities, including London.

Elizabeth McDougald, an African American woman from New York who served at a Red Cross club in London, wrote in the Afro American newspaper in March 1943 that the English were very hospitable. She worked at the Duchess Club, she wrote, which had bedrooms for 60 men, along with lounges, dining and reading rooms, and movie equipment. Their patrons included a mix of Allied soldiers – West Indians, Africans, Canadians and British. They had guides and maps that they consulted.

This club was opened for black soldiers. Charlene F. Wharton, the assistant program director, stated in the New York Age newspaper in April 1943 that the club was a place where the men “cold and tired” after a trip from camp were happy to find women from all over the United States who could relay the news from back home. She also told of four black officers who had dinner there after receiving their commissions as lieutenants.

The U.S. military authorized the Red Cross to set up clubs for all branches of the services to offer food, dancing, movies and other entertainment (most of the named celebrities seemed to have been provided through the USO), tour info and a friendly woman to talk to. Some provided barbershops and places for soldiers to do their laundry.

The clubs were located all over, from “England to India, Guam to Nigeria, China to New Zealand.” Soldiers could find a place to sleep at Red Cross hotels: There were so many of them that the organization claimed to be the largest hotel chain in the world. None of this was free, though; the military directed the Red Cross to charge a nominal fee for food and lodging.

The London Rainbow Corner in Piccadilly Circus, opened in 1942, was the largest and most popular, operating 24 hours a day with the wherewithal to serve 60,000 meals a day.

When African Americans began arriving in Great Britain that year, this was the only Red Cross club available. General Dwight Eisenhower directed his commanders to avoid discriminating against black soldiers and advised the Red Cross to accommodate them in the clubs.

The Red Cross was a willing participant in the segregationist practices both overseas and in the United States. Back home, the organization formed its Blood Donor Service after an African American doctor named Charles Drew created a system for processing and storing blood plasma, which made it easier for shipping. He was also director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank. (Interestingly, Frederick Douglass had advised Red Cross founder Clara Barton in the late 1800s.)

When the Red Cross started the program in 1941, it announced that it would not ship blood donated by African Americans, apparently at the request of the military. That set off a frenzy of attacks from the NAACP and other organizations, and from Drew himself, who now was at Howard University in Washington, DC.

The Red Cross backed off, deciding instead to code blood by race, a practice that finally ended in 1950. “It is unfortunate that such a worthwhile and scientific bit of work should have been hampered by such stupidity,” Drew said in 1944.

At the London Rainbow Corner, black and white soldiers were given passes for the club and other local pubs on different nights.

Eventually, the Red Cross opened more than two dozen clubs for African American soldiers, but the two groups mixed it up in other clubs as well. Fights inevitably broke out, and much of the trouble seemed to have come from white soldiers’ angst at the lack of segregation in London and the black soldiers’ ease with white British women.

Another Rainbow Corner opened in Paris in 1944, the first of the Red Cross clubs in that city. By May 1945 there were 15 clubs, along with “three-day clubs for feeding.”

Along with its clubs, the Red Cross also had a fleet of Clubmobiles – converted trucks and buses – that hit the road to take donuts and coffee, chewing gum, newspapers and music to troops on the front lines. Clubmobiles for black soldiers or staffed by black women were few and far between. Some African American soldiers in Great Britain complained that they were sometimes turned away from the white trucks. There apparently was only one Clubmobile with a black staff in Great Britain by the end of 1944, according to one recollection.

In an article in the August 1943 Pittsburgh Courier, Wharton of the Duchess Club in London related the story of that center’s Clubmobile visits to camps housing black soldiers. Red Cross workers arrived at the camps playing Count Basie’s “Blue and Sentimental.” They got a lot of requests for Basie and the Ink Spots, along with the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper.

“We have met newcomers from the States, men who are less than 12 hours off the boat,” said Wharton. “It’s difficult to describe how surprised they are to find us right in camp. They are usually most hungry and most curious for newspapers, magazines and games. They are full of questions about the country, where we live, whom we have seen and if there are any other Negro women over here.”

“The appreciation shown by these men for our visits is difficult to describe. They like to linger in the bus. Sometimes they say nothing at all but are reluctant to leave.”

I am the grandson of Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee, commander of all Army Service Forces (logistics) in the ETO in WWII, and therefore the vast majority of Black soldiers, men and women, who were sent over there. He lobbied the several Theater Commanders for almost three years to improve the lot of the men under him, and signed the order on 26 Dec. 1944 that allowed Black rifle platoons to serve in white units. He suffered reputationally for his progressive ideals.

On 24 May 1945 he writes in his WWII Diary:

(After dinner) “we visited (his driver) Sergeant Chambers, at the Red Cross Club, The Potomac, where we were most cordially received and enjoyed very much the singing program that was presented for us by Chaplain Carty’s choir. Returned to the (hotel) for the night.” Chaplain Carty was a Black officer and AME minister.

Your post is the only thing I found online about Club Potomac. Thanks for posting it.