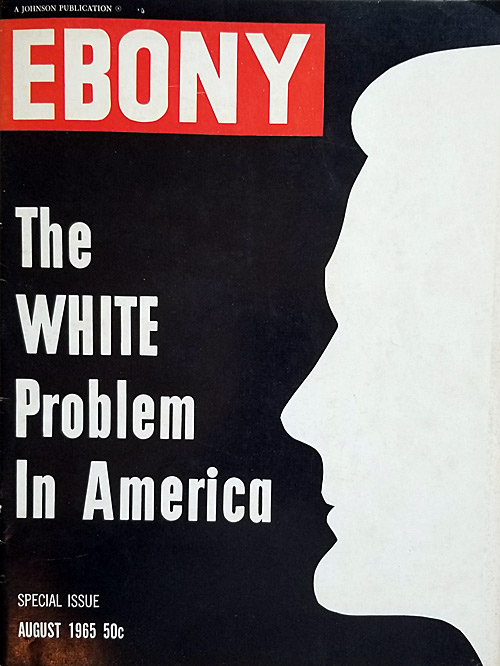

I was flipping through some magazines at auction last week when a familiar cover willed me to stop. It was an August 1965 copy of Ebony magazine with the silhouette of a man’s face in white against a black background. “The White Problem in America,” the cover blared.

It reminded me of the issue of Philadelphia Magazine that has created a stir in this city over the past few weeks. Nearly 50 years apart, the covers were remarkably similar; they both took on the issue of race from two decidedly different ways but chose the same stark cover design.

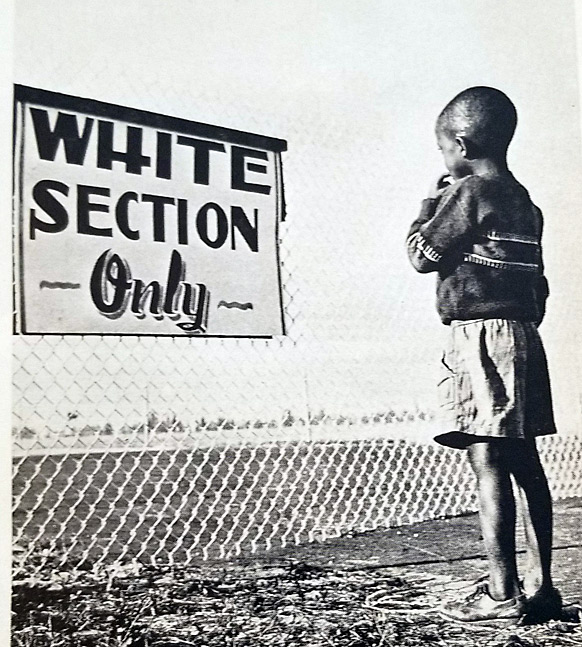

Ebony took a national view of the issue at a time when African Americans were being treated as second-class citizens but were finally rallying against their “assigned” place in American society. Philadelphia magazine seemed to be right back in the 1960s with its wrong-headed notion of who black people are.

I won’t get into the problems with the Philadelphia magazine article titled “Being White in Philly,” ; many people have talked and written about its slight stab at research, its one-sidedness and its clumping of all black people together as one monolithic group that has not gone far beyond the stereotypes.

The piece was opinion pretending to be for real.

Ebony mixed interviews, research and opinion in its articles. They were written by people who had become experts in their fields by studying the issues that they were writing about. These experts drew not only from their own knowledge, but also from research and interviews of people who knew what they were talking about, too.

This special issue of August 1965 was Ebony’s own way of trying to show that race in America was not a problem of black people. It was an “in-your-face, no-holds-barred” analysis of race from an African American perspective.

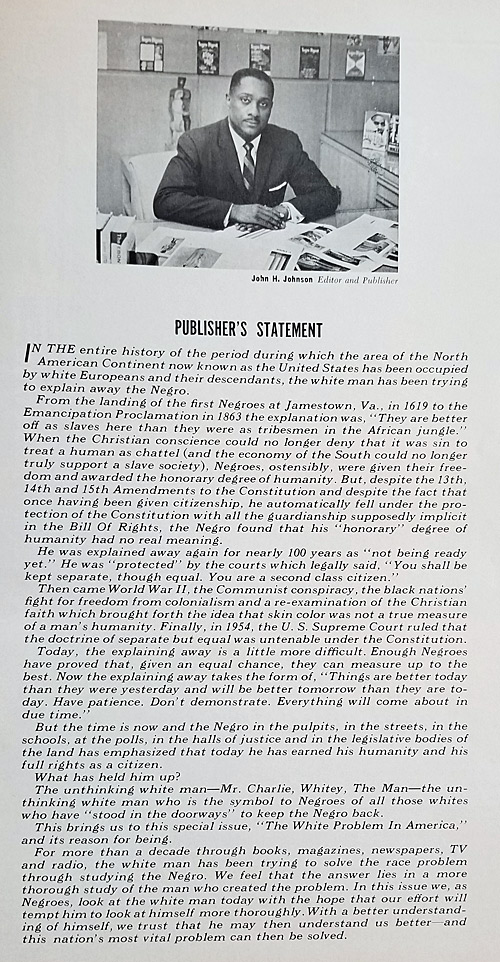

John H. Johnson’s magazine had been the voice of and looking glass for black people since he started it in 1945. He wanted to show African Americans as normal people who loved, worked, enjoyed life, got an education, achieved, had faith, and were not all poor or degenerate. His magazine took on light subjects and weighty topics, as it did in this issue.

“For more than a decade through books, magazines, newspapers, TV and radio, the white man has been trying to solve the race problem through studying the Negro,” Johnson wrote in the Publisher’s Statement. “We feel that the answer lies in a more thorough study of the man who created the problem. In this issue we, as Negroes, look to the white man today with the hope that our effort will tempt him to look at himself more thoroughly. With a better understanding of himself, we trust that he may then understand us better – and this nation’s most vital problem can then be solved.”

Added senior editor Lerone Bennett Jr., “There is no Negro problem in America.” His statement was as succinct and clear as W.E.B. DuBois’ warning at the turn of the 20th century: “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

The articles covered a range of topics relating to race:

Bennett wrote the lead story based on the title of the issue: “The white problem in America.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote about the “Un-Christian Christian.” Whitney M. Young Jr., executive director of the National Urban League, wrote about the “high cost of discrimination.”

Carl T. Rowan, chief of the U.S. Information Agency, wrote “no ‘whitewash’ for U.S. abroad.” Prof. Kenneth B. Clark, who with his wife Mamie had conducted a ground-breaking study in the 1940s about the effect of segregation on black children’s image of themselves, wrote “what motivates American whites.” Author and playwright James Baldwin wrote about “the white man’s guilt.” Hans J. Massaquoi, Ebony’s assistant managing editor who grew up black in Nazi Germany, wrote “would you want your daughter to marry one?”

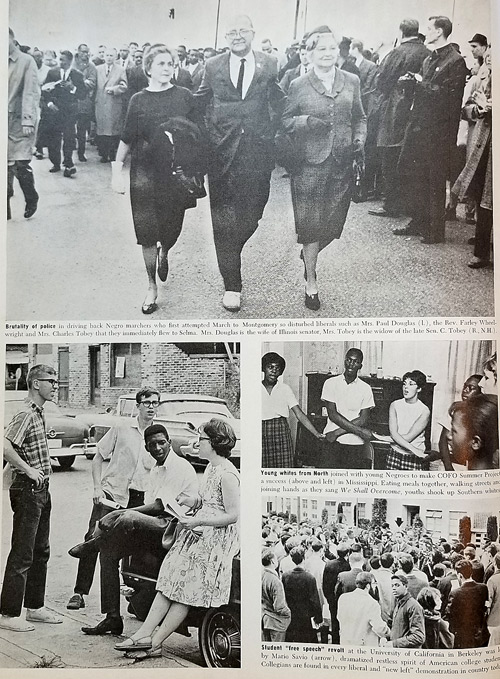

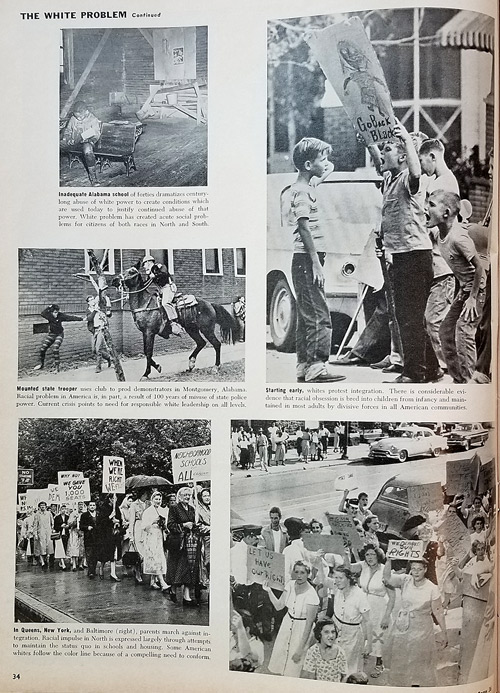

“Racial problem in America is, in part, is a result of 100 years of misuse of state police power,” Ebony stated.

This was Ebony’s first special issue, and the editors said it was a “blockbuster.” Letters to the Editor seemed to have poured in, and the articles were reprinted in a book in 1966.

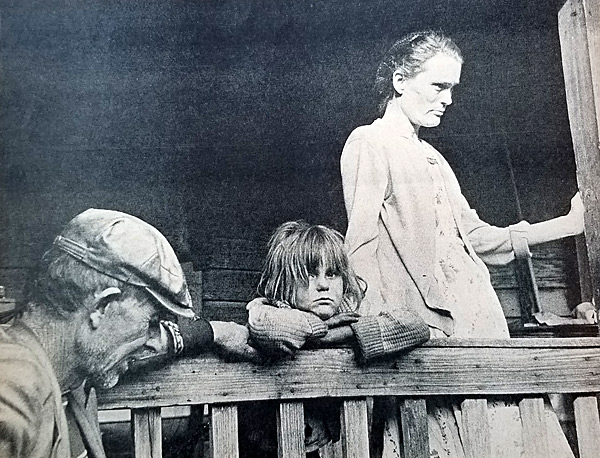

The magazine didn’t focus entirely on African Americans. At least two of the articles told the story of white families who were also shut out of the American dream and a white girl in Appalachia with very little hope of escaping her life of poverty.

It also included a story about crime in the suburbs, including drugs and pot parties, shoplifting and even a housewife prostitution ring in one New York state town.

As for fear, let us not forget that for decades fear walked side by side with African Americans, as noted in the Ebony issue. The magazine offered photos of hostile whites – among them, children – protesting school integration; white police officers outside a black family’s home after they moved into a white neighborhood, and Klan men, women and children in white robes.

So, racial fear of the other has been omnipresent in the lives of Americans, inflicted by both sides. As exemplified by the two magazines separated by decades, it’s not likely to go away anytime soon.

Hopefully, the son of the writer of the Philadelphia magazine article is learning more about African Americans he’s meeting as a student at Temple University than his father – who, by the way, lives in one of the most integrated parts of the city – is willing to find out for himself.

Nice to see someone discover and respond to the special issue of 1965. I’m one of the few surviving contributors. I wrote the article on “White Hate Groups.” Unfortunately, too many of them are still around, and now some seem to enjoy the tolerance, if not support, of the elected leader of this country.