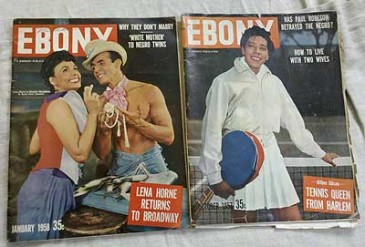

As we stood in her basement, the woman wanted to show me a photo of her family in an old copy of Ebony magazine underneath some papers. I had seen one Ebony and an early Life magazine on a table, but glancing at the dates I had bypassed them.

Normally, I’d thumb through magazines looking for historically interesting articles, especially Ebony magazines because I was on the hunt for a particular story. It wasn’t a story exactly, but an advice column written by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from 1957 to 1958.

I had read a Washington Post story last year about the column. And I was immediately intrigued that the man who nonviolently shook a country out of its stubbornness to acknowledge its African American citizenry and ancestry would be right up there giving advice alongside Ann Landers and Dear Abby . (Both, by the way, had begun writing their columns a year or two earlier).

It seemed so ordinary for a man of his stature. But I was curious about what people asked of him and what he had to say.

After I saw the “October 1957” date on the cover, I was immediately excited. I went straight to the Contents Page, slid my finger down the list and at the bottom saw “Advice for Living by The Rev. Martin L. King …….. 53.” I did the same with the other magazine dated January 1958 and found the column on page 34.

It was like finding buried treasure, because I had checked every Ebony magazine I’d come across at auction – and there weren’t many – and hadn’t found one. And here was not just one but two of them.

I flipped through the first magazine with its musty odor, past photo after photo of black people in Vicks Vapo Rub, Vienna sausage, bleaching cream and Admiral TV ads – black people living normal lives (albeit most were fair-skinned) – and finally came to it.

There in the right corner was a familiar black-and-white photo of King, and on the page were six questions and answers followed by an address for readers. Most of the questions were of a religious nature, even in the context of race:

“Question: I’m confused. I hear some men of God argue persuasively in favor of segregation and then others say it’s sinful. I would like to know once and for all, with no ifs, ands and buts, can a man be a Christian and a staunch segregationist, too?

Answer: I do not feel that a man can be a Christian and a staunch segregationist simultaneously. All men, created alike in the image of God, are inseparately bound together. This is at the very heart of the Christian Gospel. This broad univeralism standing at the center of the Christian Gospel makes segregation morally evil. Racial segregation is a blatant denial of the unity which we have in Christ. There is not a single passage in the Bible – properly interpreted – that can be used as an argument for segregation. Segregation is utterly unchristian. It substitutes the person-thing relationship for the person-to-person relationship.”

King was said to have been asked to write the column by Lerone Bennett Jr., associate editor of Ebony and a Morehouse (University) brother of King’s. The monthly column ran for a year from September 1957 to December 1958. It was during the early days of King’s activism, and he was beginning to establish his place and stature in the civil rights movement.

More than a year before, he had successfully led the Montgomery (AL) bus boycott that kept black folks off the city’s buses for more than 380 days. During the protest, King’s house was bombed and he was arrested. The boycott ended with a ban on segregation of the buses.

In 1957, he helped organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to coalesce churches around the principle of non-violence to effect change in the discriminatory culture of the country. He became its first president, and that helped catapult him into a leading national civil rights figure. King and the SCLC held mass meetings throughout the South to register black voters, and he met with black leaders and held lectures throughout the country.

He was the man of the hour and he was still in his 20s. For Bennett and Ebony, I’m sure, the time was ripe and the populace was willing. When you think of it, it wasn’t much different from how people are marketed and branded today when they’re at the top of their game.

Ebony promoted King with a full-page ad in the Sept. 7, 1957, edition of its sister publication Jet. The ad and word of the column apparently got around because the magazine was inundated with letters, according to The Martin Luther King Research and Education Institute website. The site has correspondence – including readers’ questions and King’s answers – back and forth between Bennett in Chicago, and King and Maude L. Ballou, King’s longtime secretary, in Montgomery.

The first column in September 1957 contained two questions, including one on interracial marriage. Over the year, King answered questions on an array of subjects ranging from women, homosexuality, gambling, Christianity, morality and more.

This is one from the January 1958 edition:

“Question: I find so many Negroes trying to be everything but a Negro. Why is the Negro so ashamed of his race? Why can’t you find books about Negroes in the homes of Negroes?

Answer: A sociologist has recently written a work in which he affirms that the Negro middle class has no cultural roots because he rejects the culture of the masses of Negroes and is himself rejected by the white middle class with whom he seeks to identify. This lack of cultural roots leaves him victimized with a tragic sense of inferiority and self-hatred. This analysis, while lacking at some points, has many elements of truth. The Negro must always guard against the danger of becoming afraid of himself and his past. There is much in the heritage of the Negro that each of us can be proud of. The oppression that we have faced, partly because of the color of our skin, must not cause us to feel that everything non-white is objectionable. The content of one’s character is the important thing, not the color of his skin. We must teach every Negro child that rejection of heritage means loss of cultural roots, and people who have no past have no future.”

King continued to write the column up until the time he was stabbed with a letter opener by a mentally ill woman named Izola Curry as he signed copies of his book “Stride Toward Freedom” in a Harlem department store in September 1958. His doctors, according one site, had recommended that he cut back on his work.

Ebony had proposed that he start writing an opinion column in 1959, but it never happened.