As soon as I saw the metal token on the auction house website, I recognized it. It held an image of a woman on one knee, her hands chained and raised heavenward, asking for a freedom that was denied her.

It was an anti-slavery token or coin, and the image had been borrowed from a medallion created in 1787 by renowned English potter Josiah Wedgwood as a symbol for abolitionists fighting the slave trade in Britain. His was made of the material of his famous pottery – Jasper (but in black and white) – and the human in bonds was a man and not a woman.

I had come across a photo of this token about two years ago when a 20th-century reproduction of the Wedgwood medallion came up at auction (it sold for $325). So I was happy to actually see one of the coins.

When I arrived at the auction house, I looked for the glass case with the token because I wanted to hold it in my hand, to look at it closely, to feel the history embedded in it. Imagine my surprise when I saw that there was not just one but two of the copper coins. Some of the tiny details had been rubbed out by so many other touching hands for nearly two centuries, but they were still in good condition.

Around the edge were the words: “Am I Not A Woman & A Sister. 1838.”

On the reverse side: “United States of America (The N was backwards). Liberty. 18 (the rest of date was partially rubbed out).”

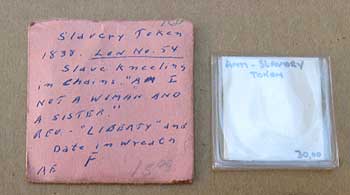

One of them was in a small envelope with penciled writing that identified it as a slavery token, along with the date, description and “Low No. 54,” referring to, from what I could determine, the grade of the coin. It was priced at $15.

When the tokens came up for bids, the auctioneer pulled out another one lying inches away from the woman. Tucked in a small plastic pack was the male companion, its color a little darker, its image like that of Wedgwood’s. How had I overlooked it?

It did have one difference: One wrist and one ankle were shackled. On the woman, one wrist was shackled and the other end of the chain lay in front of her feet. Inscribed in a half-circle around his edge: “Am I Not A Man and A Brother.” On the back: “May Slavery and Oppression Cease Throughout the World.” There was no date on it.

Now, I was very excited. When the auction got underway, though, I was not the only one interested. The bidding bounced back and forth between two of us buyers until it stopped at $30 each. That was the price printed on a tab of paper in the case with the male.

The two were “Hard Times” tokens manufactured in 1837 and 1838 when money was scarce and the economy was bad. Merchants bought them cheap and used them as one-cent change pieces. They sported ads for businesses, along with political slogans or causes. More of the female versions were apparently made than the male. Some of the male were said to be rare. There apparently were other grades of the female.

Up to 200 hard times tokens may have been minted, and they were widely circulated. The American Anti-Slavery Society issued the kneeling woman through its newspaper. The society enlisted a New Jersey company to strike the tokens, which were sold for $1 per 100. It announced that it would also sell the male tokens, but that apparently was never done. It did offer a version imported from Britain, according to one website.

Among the members of the society was an African American named Patrick H. Reason of New York, who in 1835 engraved a kneeling woman based on the Wedgwood figure. The society commissioned several pieces by him, but I could not determine if this was one of them. Some sites said the female image was derived from his engraving, but I wasn’t able to verify that.

No one seems to know who created the female image, but it apparently was first used in England in the early part of the 19th century. It appeared in print in this country around 1830. It was popularized by Elizabeth Margaret Chandler, a white woman who advocated the abolition of slavery in her writings and poetry, including the poem “The Kneeling Slave” around 1833. African American abolitionist Sarah Mapps Douglass, who was active in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, sent her a drawing of a kneeling woman after seeing the poem in print.

The female tokens were sold by women organizations to fund their anti-slavery campaigns. (Here are some other items that used the symbol.)

Several sites noted that the token was listed as No. 10 among the 100 Greatest Tokens and Medals in a book by Katherine Jaeger and Q. David Bowers.

i have a set of copper slave statues reproductions. they are two slave men kneeling with chains on wrists and ankles. one still has the pedestal, the other missing. the words Am I not A Man and A Brother inscribed along the side of pedestal. i live out in an isolated part of oregon and have found some amazing artifacts of history here. i had to bring these home to my house. they have been exploited enough. maybe one day these pieces will be part of an educational museum in portland for the children.