We had driven past the headstone when my friend Valorie called out for me to back up the car. She was in the back seat quietly looking out the window for the granite stone that marked the graves of her grandparents Lillyan and James Fassett.

How had we missed it? I put the car in reverse and moved backward very slowly. Then she spotted the fallen headstone. The top piece had toppled from its base, lying there on a small hill, slightly embedded in the soil at Eden Cemetery. I’m sure it was like a dagger through Valorie’s heart.

I parked the car, we got out and headed to the structures. “Hmm, hmm, hmm,” she said. “I’m glad my mother didn’t see this.”

Then she went to the office to see what could be done, and for the next hour or so she talked to anyone associated with the cemetery to make sure the headstone was erected. A cemetery official told her later that it had likely been toppled by the packs of deer that roved through the cemetery.

I could understand why. It was a very verdant place that seemed to go on forever. Nothing like the macabre eery image of cemeteries from horror movies (even though we did joke that we didn’t want to see a hand shoot out of the ground). With a constant gentle breeze sweeping away the sun’s heat, it was rather relaxing and quiet.

We were there on a day when the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists had enlisted photographers to chronicle the country’s oldest public African American cemetery, founded in 1902 by Jerome Bacon. The PABJ had teamed with Global Citizen, sponsor of the Greater Philadelphia Martin Luther King Day of Service, and several other organizations for this history-preservation project. Here’s a video of earlier cleanup work at the cemetery, and a newspaper story about plans to make it into a historical site.

I don’t come across much at auction pertaining directly to cemeteries and funerals, except for a granite headstone once that was inscribed “Mother.” What I do find on the auction tables are the remnants of the lives these people had led: photographs, jewelry, household products, and just about anything else you can think of.

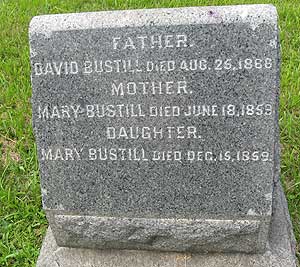

There at Eden Cemetery on Saturday, I walked among them. Some of the graves had been moved from other cemeteries and brought there, and some of the headstones dated back to the 1700s, said cemetery staffer Carolyn Gibson Harris.

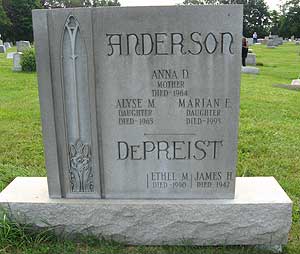

The cemetery also contained the graves of some of the country’s most famous African Americans. Marian Anderson is buried there. Her headstone also bore the names of her mother and sisters, and sat on a mound near the main road close to the entrance gate.

Not far from her – and you couldn’t miss it – was a giant dark gray marble headstone for the Rev. Charles Albert Tindley, considered one of the founding fathers of gospel music. In the same section – the cemetery is divided into sections named after famous people, former cemeteries whose remains were moved to Eden, and others – was John Baxton Taylor, the first African American to win an Olympic Gold Medal in 1908.

I was on the hunt for the grave of the writer and activist Frances E.W. Harper, and had a hard time finding it. With a little help, I finally did. Her headstone was in a back section on a hill that looked out over the front area of the cemetery. Next to it was a marble headstone with the words from one of her poems (“Bury me in a Free Land”) along with her name and her daughter Mary’s name.

She shared the section with the noted abolitionist William Still, considered the father of the Underground Railroad, and across in another section, 19th century Philadelphia activist Octavius Catto.

As I roamed the grounds, I took the time to stop and read the other headstones. I’m always amazed to see the names of people who were born and died in slavery, or who were born in slavery and died at the end of the 19th century or the early 20th century. I’m sure they had some stories to tell, and I wondered if they ever told them. Or did they consider their lives not worthy of repeating.?

Seeing old graves always puts our lives in context: We don’t exist in a vacuum, people lived and loved and fought and survived the best they could just as we do today.

Like the Potter family, whose plot was bordered by a low stone wall. Inside was an obelish with a dedication to Elizabeth Potter, and on the ground were headstones of other family members. The sweetest one read: “Little Eddie, First in Heaven.”

I also noted the graves of veterans of World War I and II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, each with a small American flag beside it.

Harris pointed out two graves of African American Civil War soldiers: Jacob Gardiner, whose headstone listed him with the 25th U.S.C.T. (United States Colored Troops), and Johnson (I couldn’t make out the initials on this very old headstone) of the 7th USCT. The cemetery had erected small US flags near their graves with a GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) medallion.

Harris actually studied to be an arborist but accepted a job to work with the cemetery on its grounds. That’s understandable, since she has personal ties to it. She’s a descendant of Nellie Bright, who was a teacher in the Philadelphia public schools and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania in 1923, excelling at a time when blacks weren’t given very many opportunities to do so.

“All of my people are here,” she said. “I’m fourth generation.”

Valorie has more people there, too, but we didn’t get a chance to find their resting places. She did recall those times as a child when her grandmother Lillyan came to tend her husband’s grave. Back then, she said, the grounds were a mess (on Saturday, they looked well-tended). Lillyan was 12 years younger than James, who died in 1938, leaving her to raise their seven children. She died in 1991.

After cleaning up the grave, Valorie recalled, her grandmother would spread out a blanket. “Then we would have a picnic.” After Lillyan died, “I used to drive my mother all the time” to spruce up the graves, she said. “Her brothers used to put flowers on the grave.”

All except one of them are gone now, and it’s up to her to make sure the headstone remains standing as a sign of respect to Lillyan and James.