The two women waited patiently in the plain chairs at the auction house, through more than three hours of bidding on Chinese vases and furniture, mantle clocks, shoe-store furniture, stained-glass windows and then artwork by people they had never heard of.

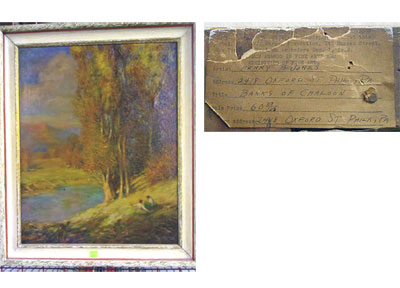

Then the auctioneer finally got to the painting that Isabel and Lucille Hamill had come for. It was a landscape titled “Banks of Chaloon” by African American artist Henry B. Jones. The painting had special meaning to them because Jones was their Uncle Henry, the man who had lived across the street from them and whose house they were always in and out of as children.

They wanted this oil on canvas for his granddaughter who had already picked a place for it in her home. (Click on photo above for a fuller view.)

“She loves her grandfather’s work,” said Isabel. They also wanted it “just because it was his,” as one sister said.

The women had their auction number and were ready for the bidding, which started at $1,300. But they weren’t the only ones who wanted the painting. There was one avid bidder on the floor and at least one other online. At one point, another person on-site dipped his toe in but stepped out pretty quickly.

The bids kept rising and rising – past $2,000 and then $3,000, with no let-up in sight. The sisters dropped out – “I don’t have that kind of money,” one of them said later. It sold for $9,250.

A label on the back showed the painting’s history: It had been exhibited in the Harmon Awards in Fine Arts and Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1929. The Harmon Foundation was a major patron of African American artists during the first half of the 20th century. Jones exhibited in Harmon shows in 1930, 1931 and 1933.

The auction house had gotten the painting from the niece of a former Philadelphia school teacher but Rob Goldstein, the art expert at Barry S. Slosberg Auctioneers – which sold the painting – wasn’t sure how the original owner had acquired it.

“He was experimenting with the impact of color in a very direct way,” Goldstein said of Jones. It reminded me of the impressionist works of African American artist Edward M. Bannister, who had painted during the 19th century.

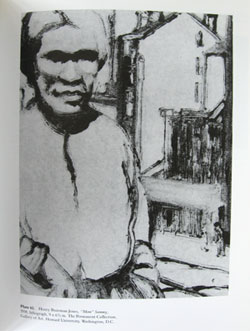

Jones had not always used color. His early works were more “academic,” according to the book “Against the Odds: African American Artists and the Harmon Foundation” by Gary A. Reynolds and Beryl J. Wright, published in 1989 as a catalog accompanying an exhibit at the Newark Museum in New Jersey. The authors said his style changed after a trip to North Carolina and the Bahamas in 1937.

“He loved colors,” said Isabel. “His early paintings … looked like they were done by a different person. It was a totally different style. He brought in more colors and more abstract kinds of things.”

Lucille recalled that Jones, who died in 1963, didn’t like the color black at funerals. For his own service, he told them, he wanted everyone to wear “blues and greens … like a palette.” At his funeral, his grandchildren “looked like a rainbow,” she said. “They did just what he wanted.”

Jones was born in Philadelphia in 1889 and attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from1908 to 1910, according to Against the Odds. He taught physical education at an elementary school in the city and painted on the side. He also authored and illustrated a children’s book for the public schools.

Crisis magazine in January 1913 mentioned him becoming skilled in portraiture, including two that he had done of Frederick Douglass.

In the Harmon shows, Jones offered nature scenes and religious themes. He also exhibited at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) in 1933. His other group exhibitions included the 1944 Atlanta University Third Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Sculptures and Prints by Negro Artists: The Two Generations. The Howard University Gallery of Art has several of his works.

Jones’ paintings have come up for auction at least two other times within the last 10 years, according to my Google research. Sotheby’s sold “Jazz Quartet” (signed H.B. Jones) in 2006 for $19,200, and Sloans & Kenyon auction house in Chevy Chase, MD, sold “Sun-Dappled Forest” for $6,400 in 2007.

Lucille and Isabel also remembered Jones participating in a group show at a recreation center in the city and finally at the Philadelphia Art Alliance around the 1940s or 1950s. “It was hard for black artists to get known and have their pictures seen,” said Lucille.

When the sisters were young, blacks around Philadelphia would come to Jones’ house and buy paintings from the man friends called “Hen,” whose works included landscape paintings, linocuts and lithographs. “He might sell it and he might not,” said Isabel.

The sisters have some of their uncle’s paintings, including one of Lucille at age 15. Jones also painted his son Henry Jr. who was trained as a navigator in the military but never got to use his skills because he was black. “He painted him in uniform,” Lucille said.

They remembered their uncle as a loving man who was straight-laced and had a commanding voice. “When he would say, “Well,” you would start shaking in your boots,” said Isabel, who like her sister is a former school teacher. “You knew you had done something you shouldn’t have done. You don’t want to hear Uncle Henry call your name.”

“It was his method of control,” Lucille said.

Jones’ studio was a second-floor bedroom in his home, and the sisters recalled seeing him paint. “I can see him in his studio with his pipe or reading the newspaper,” Lucille said. “On weekends, we weren’t allowed to open the funnies until he had a chance to look at (the paper).”

“One of the things he did that I’m thankful for,” she said, “was that he made us see beauty in many many places.” He was telling them this at a time when light skin and so-called good hair were being used as the determinant of beauty in the black community.

“He’s the one who taught us that what’s important is what’s inside a person’s head and not what’s on top of it,” added Isabel.