The first photo among the black and whites showed the proud stoic face of a Native American man. He wore two long braids on either side of his head, a pompadour framing his forehead, eyes staring to the left.

Across his chest was a sash with symbols, and just beneath it, someone had affixed a sign that read “Chief Joseph.” The back of the photo bore some faint writing that looked to have been erased.

The second photo was of the same man, years older, with the same pompadour, his neck heavy with beads. That photo bore the name of the Schoenfelder & Kehle photo studio in Newark, NJ.

The images of Chief Joseph, one of the hero chiefs whose warriors fought valiantly against the U.S. Army in the 19th century, were among a dozen photos that I bought at auction recently. They were two of three mounted on board; the third was of a man who looked to also be a chief – or elder – photographed by F.S. Richardson of Napanee, Ont.

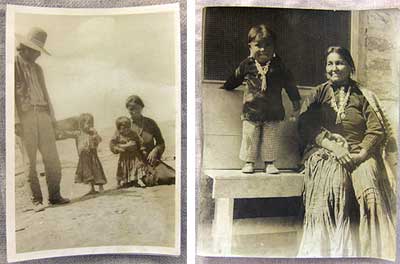

Along with the studio portraits were other sepia or brown-tone prints of Native Americans in front of their homes and in other surroundings. Three have notations written in pencil on the backs: “1912,” “Pueblo Bonuto Kayenta” and “Menomipee, Wisc. 1917.” So, the photos are apparently from the early part of the 20th century.

The writer was referring to Pueblo Bonito in northwestern New Mexico and Kayenta of northeastern Arizona, two of the great centers of Pueblo life from 11th to the 14th centuries. Navajos, descendants of the Anasazis who peopled the two areas, were living on a reservation in Kayenta at the turn of the century. Menomipee refers to the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin.

It’s not often that I stumble on photos of Native Americans at auction – I did pick up some stereoview cards of photos from an 1870s expedition to survey the west. I knew that I wanted these new ones and was hoping that not many other auction-goers were interested.

I was wrong, and I went tit-for-tat with one or two other people – at one point giving up the chase but then jumping right back into it. Finally, the last of the competitors stopped bidding and I got the stash.

I’m glad that I did because of the history attached to Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War (pronounced Nes Purse) of 1877. For four months over 1,400 miles, the chief and his band of warriors, women and children eluded and fought the U.S. Army.

Chief Joseph was born Hin-mah-too-lat-kekt (“Thunder Rolling Down a Mountain”) in 1840, the son of the chief of one of several Nez Perce tribes in northeast Oregon. His father had offered assistance to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and early on had allowed whites to travel through their land on the way to elsewhere.

That peace was disrupted, though, when the U.S. government decided to force the Nez Perce onto a reservation in Idaho in the early 1870s. By then, Chief Joseph – who had been baptized a Christian by missionaries – had taken over from his father, and he ultimately agreed to leave rather than engage in war. Along the way, though, some warriors angry about giving up their homeland and the loss of their peoples’ lives to settlers retaliated. Fearing trouble from the government, the chief sided with them.

He and his band headed out on their own to live among the Crow people. They beat off the U.S. Army in skirmishes along their trek – the military tactics and prowess said to be the work of his brother and other warriors. Rebuffed by the Crow, they looked toward Canada to join Sitting Bull and the Sioux who were given sanctury there after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. They got 40 miles from the border, but weak and tired, they could not make it any farther (although some of them did manage to escape).

Chief Joseph surrendered and agreed to go to Idaho with the more than 300 people left. They made it no farther than Oklahoma, where they were treated as prisoners of war. Finally, some were allowed to continue to Idaho, while Chief Joseph and others went to Washington state. He remained a spokesman and advocate for his people until he died in 1904. He is much heralded and celebrated today.

During this time of the country’s western migration, photographers scoured the area to capture images of Native Americans – some stereotypical, some real – in studios and in their natural surroundings. The photos were sold as souvenirs in the form of cabinet cards, boudoir cards (larger than cabinet cards), and stereoviews or stereographs.

The first photo of Chief Joseph was taken around October 1877 by John Fouch after the chief’s surrender. The younger photo of him from the auction was taken in the same year, presumably in a studio in Bismarck, ND, but there is some question about who actually took it. Photographers Orlando S. Goff, D.F. Barry and Frank Jay Haynes all purported to have shot the picture.

Most sources cite Haynes as the original photographer. Both Haynes and Goff had studios in Bismarck from the late 1870s to the 1880s.

The second photo of the chief as an older man was a studio portrait taken by Edward Curtis in 1903 in Seattle. The chief had come to Seattle seeking return of his family’s homeland.

Starting at the turn of the century, Curtis photographed and put together an archive of 40,000 Native American images – along with recordings of their lifestyle and culture – over 30 years. Swann Auction Galleries in New York last year sold a complete 20-volume set of Curtis’ books for $1.2 million (without buyer’s premium).

The third photo was apparently not Chief Joseph. In my Googling, I found that the man may have been from the Mississauga people who lived in the Napanee area. A line of Richardsons were both artists and photographers in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

If you have any more information on the photos, please contact me in the Comments box below.