When I first saw the books and their titles in the glass case at the auction house, my first thought was of cameras. The images on the covers, though, were of strange little characters with skinny legs.

They were incongruous to my sense of what a Brownie was: those black boxy cameras first made at the turn of the 20th century by the Eastman Kodak Co. I wondered if and how they were connected.

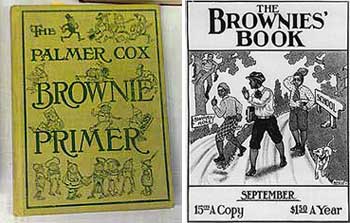

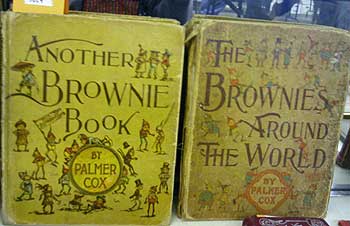

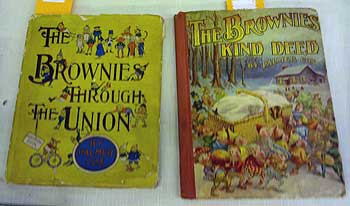

The case contained about a half-dozen books with such titles as “The Brownie Primer,” along with two paper ice cream sandwich bags. As I flipped through one of the books, I saw poems and tons of illustrations of the little men.

Intrigued, I wanted to know more about the Brownies.

The books were written by Palmer Cox, and were immensely popular from the 1880s to the early 1900s (he died in 1924). The tales were based on Scottish lore told to him by his mother as he was growing up in Granby, Quebec, Canada, during the 19th century. The Brownies were mischevious and adventurous fairies who engaged in harmless pranks, their existence entertwined in the lives of the people who believed in them. They were the right sort of characters that would be endearing to children.

But my research into the Brownies took me on a very different and exciting path. I also found out that Brownies was part of the title of a magazine that W.E.B. DuBois created for African American children in 1920. It was a child’s counterpart to the NAACP’s Crisis magazine – “to make colored children realize that being colored is a normal, beautiful thing,” DuBois wrote.

I had heard of neither Cox nor DuBois’ Brownies, but I certainly was familiar with the Kodak camera. I’ve come across many of them at auction, dating from the 1920s and later. The company made photography available to the masses with its simple-to-use and even-cheaper-to-afford box cameras.

The Brownie camera got its name from Cox’s cultural phenomenon, which he apparently licensed and commercialized to the hilt. The Brownies are said to be the first to have their own line of products, including dolls, puzzles, games, cards, calendars, mugs, toys and soap.

The characters first came to life in 1883 in the children’s magazine St. Nicholas. Four years later, Cox pulled those stories together in his first book “The Brownies, Their Book,” followed by more than a dozen others and a stage play. Some of the Brownies represented other peoples, including Native Americans, Chinese, Scots and Irish, but apparently no African Americans.

It was against this backdrop that DuBois started the Brownies Book for black children, five years after he had written and campaigned against D.W. Griffith’s anti-black movie “The Birth of a Nation.” DuBois noted that while the magazine was designed to teach racial pride and black achievement to them, it was just as important for all children.

The Brownies’ Book was pure propaganda, and DuBois made no excuses for its purpose:

“I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.”

The magazine presented the positive side of black life, showing them doing the things that they ordinarily did daily but was not chronicled in the mainstream media. It included short stories and poetry by such writers as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Nella Larsen Imes and Georgia Douglass Johnson; folktales of African origin; fairy tales; bios of prominent black people; puzzles; letters from children and positive photos of black people.

It also included illustrations by such African American artists as Laura Wheeler Waring, Marcellus Hawkins, Hilda Wilkinson and Louise Latimer (some whose names were new to me).

Novelist Jessie Redmon Fauset oversaw the content, and Augustus Granville Dill was its business manager. The 32-page monthly magazine sold for 15 cents a copy and $1.50 for a year’s subscription. Unfortunately, it didn’t generate enough interest and was shut down after 24 issues in 1921.

An anthology of the best of the book’s selections was published in 1996.

Around the same time, Carter G. Woodson founded a publishing company that produced books for African American children. Among its illustrators a decade later was artist Lois Mailou Jones.

At the auction, Cox’s books were snapped up by bidders, and most were sold in pairs. The most expensive went for $65, and included “The Brownies Through the Union.” The ice cream bags weren’t so popular. They sold for $2.