Lying discarded on table after table in the back room of the auction house were piles and piles of books from someone’s library. The auctioneer kept saying that the books and more tables of stuff were from “the same estate.”

The books were museum exhibition catalogs, Sotheby’s auction catalogs, biographies of famous artists. Most with publication dates before the 1950s, some a bit tattered with yellowing pages, others antiques.

The one that captured my eye was lying with a group of others that had some age to them. It was a special edition of the French art magazine L’Illustration, with photos and text from the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

I have a special interest in the fair because African American sculptor Augusta Savage created her piece “The Harp” for it. So, I wondered if this French magazine – produced in a country that welcomed and embraced African American artists and musicians – included her work among the exhibits.

Starting at the front of the oversized July 1939 issue of the magazine, I ever so carefully started flipping. Past the wonderful full-page ads of French perfume and cute babies. Past the photos of exhibits from Portugal and Brazil and US steel, with all the text in a language I could not fully understand.

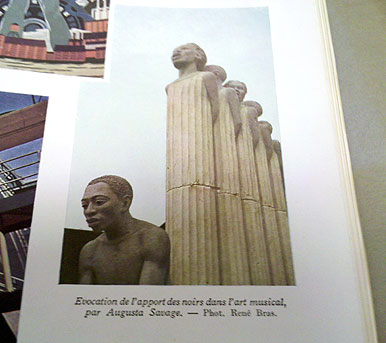

One third the way through the book, I came to it: In the bottom right corner was a color photo of “The Harp.” The French had done it. Had this been an American publication, I doubt that Savage’s sculpture would have made it into the magazine.

One third the way through the book, I came to it: In the bottom right corner was a color photo of “The Harp.” The French had done it. Had this been an American publication, I doubt that Savage’s sculpture would have made it into the magazine.

The caption read:

“Evocation de l’apport des noirs l’art musical, par Augusta Savage – phot. Rene Bras.”

I shouldn’t have been surprised, though. Many blacks had made their way to Paris in the decades before the fair. They had gone for some of the same reasons as Savage: to escape racism in their own country.

From 1929 to 1931, Savage spent two years exploring and sculpting in the City of Lights. She went there to study, to exhibit and to feel what it was like to be free, according to the 2001 book “New Negro Artists in Paris” by Theresa Leininger-Miller.

Savage arrived at a time when Paris had discovered African art, jazz and black entertainers – the belle of the ball was Josephine Baker. Many black painters, writers, musicians and even solders flocked there – with most living in Montmartre, the hub of the black expatriate community. Savage also traveled to Germany and Belgium.

Savage arrived at a time when Paris had discovered African art, jazz and black entertainers – the belle of the ball was Josephine Baker. Many black painters, writers, musicians and even solders flocked there – with most living in Montmartre, the hub of the black expatriate community. Savage also traveled to Germany and Belgium.

It had not been an easy road for her to get there. Six years earlier, she had been denied a scholarship offered by the French government after some objected to her race. She later received financial help from friends and benefactors, including the Julius Rosenwald Fund, the Carnegie Foundation and donations from teachers at the then-Florida A&M College.

By the time she arrived, she was already a well-known sculptor. She produced 18 to 22 pieces of artwork while in Paris, according to Leininger-Miller, many of which are apparently lost. She met with some of the most well-known blacks living there, including sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, painters Henry Ossawa Tanner and Palmer Hayden, and poet Countee Cullen. She attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and studied with sculptors Felix Benneteau-Desgrois and Charles Despiau. She got her chance to exhibit at several Paris salons, and she received citations from several others.

In Paris, she sculpted African women, nudes and dancers. Living in the city gave her the freedom to go in a direction that she could not have done in the United States, according to Leininger-Miller, breaking away from the usual conventions and images. Her sculpture “La Citadelle Freedom,” above right, was done in 1930.

Savage returned to the United States in 1931, her fellowship money running out as the depression ran in. In 1939, she was commissioned to create a piece for the World’s Fair to depict the musical contributions of African Americans. “The Harp” was inspired by the James Weldon and J. Rosamond Johnson’s song “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” considered the Black National Anthem. The sculpture was made of plaster, and was destroyed when the fair ended – like so many other works created specifically for it. She eventually moved to Saugerties, N.Y., for 15 years.

The sculpture was considered the highlight of her artistic career, seen and appreciated by more than five million visitors, according to Leininger-Miller. I found on the web some amateur film from Prelinger Archives that showed the sculpture, which was located in the court of the Contemporary Arts building. Forward to time stamp 7:49-8:20 to see the sculpture.

It’s only fitting that L’Illustration paid tribute to her by including it in the magazine.

I was so happy to see your article about Augusta Savage. I was an Art Major and am now an Art Therapist and I just learned about Augusta Savage this year! I am doing a presentation on her and her work for an Art Therapy PhD program at the Dominican University of California. Thank you for your work.

Hi Raceal, so happy that you’ve discovered this amazing artist who like too many are still unrecognized. Good luck on your presentation.